NACE Journal / Summer 2024

Award-winning author Barry Finlay said, “Every mountaintop is within reach if you just keep climbing.” That is what we taught the millennial generation, considered by many to be the most educated generation.1 Parents and educators instilled in millennials that their career was inextricably linked to their college major and educational experience. Career preparation was transactional in nature. The “who am I” conversation and dialogue about personal interests, talents, and skills were scarce or missing from the career planning experience. As career practitioners now prepare Gen Zers, nontraditional students, and mid-career changers, coaching conversations have shifted in context. Discussions about a student’s career path naturally integrate their academic identity, interests, and social intersections. Shifts in the educational space dictate the need to revisit, revise, and reframe traditional practices to be relevant to the needs of current students. In other words, transformational practices must replace more conventional career prep and readiness approaches.

The purpose of a university career center is to help students with their level of career readiness and decide on their career choices, and to address their needs. College freshmen primarily attend college to prepare for employment.2 Therefore, they must be equipped with skills related to their major or field of study. As students cultivate their career path, career practitioners identify 1) the best practices to guide them to their occupational title, 2) who will provide the map to their career choice, and 3) what career assessment and career advancement benchmarks will be used to help them achieve their career goals. While career professionals navigate this journey with students, it is imperative that these professionals collaborate with their career practitioner colleagues, faculty, and education stakeholders to engage in meaningful conversations to co-create the vision for the transformational student career engagement experience.

Research indicates that students who identify as first-generation, BIPOC, and/or LGBTQIA+, and those with disabilities are disproportionately affected by trauma and life deterrents.3 As a result, these students face multiple barriers to accessing sustainable and satisfying employment opportunities. Thus, the goal of student support resources—including career services—is to work with all students who are represented in the student body and maintain a welcoming environment where all students feel safe and experience a genuine sense of belonging. Engagement begins with empathy, which is spurred by actively listening to students and their expressed interests and needs with openness and fairness. Access materializes for students who are plugged into an empathic educational community that accepts, understands, and respects who they are.4

The Career Practitioner-Student Experience

Career counselors must know and understand the students they serve. In consideration of the diverse, emerging needs of students, the empathy deeply embedded in social awareness and relationship management must also fuel personal self-awareness. Goleman’s emotional intelligence model stresses that continuous self-checks and self-reflection are prerequisite to managing the emotions and needs of others.5 Accordingly, career counselors must examine their own mental models and investigate their personal worldviews to become sensitized to the needs of students who trust them as knowledgeable experts and coaches in their college-to-career journey.

The National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) Career Readiness Competencies are eight competencies that all students need to transition to the workplace—career and self-development, communication, critical thinking, equity and inclusion, leadership, professionalism, teamwork, and technology. Using the career readiness competencies as one of the benchmarks of student success challenges student affairs professionals to work together to differentiate services provided. Accordingly, academic advisers and career counselors are integral to a student’s college-to-career experience.

Academic advising and career counseling are both critical roles in supporting students in their academic and career journey. Each provides guidance and support for a student's educational needs. Academic advising and career counseling are equally important and vary in levels of influence on a student’s educational decision-making, as students become empowered to explore, as well as discover and uncover their interests. Academic advising and career counseling are two approaches that are different through their focus and scope, timeline and purpose, nature of the relationship, and outcome and impact.6 The advising relationship is formal and structured with a focus on academic or program-specific guidelines, and it is meant to be short term.7 It is a transactional exchange designed to provide student support with achieving their academic goals. An adviser makes sure that students remain on track with their academic requirements, graduate on time, and are strategic in course selection. The adviser-student relationship focuses on academic success and progression toward graduation.

A career counseling and career advising relationship focuses on a student's career path and life trajectory. The interaction may include career planning and assessments, goal setting, skills development, job-search strategies, personal growth expectations, and mentorship. A career counselor/adviser partners with students and alumni throughout their career. The relationship with a career services professional is holistic. Personalized, collaborative, and intimate conversations that ensue help students to navigate their own identity, life experiences, and interests. Career self-assessments, the exploration of interests and values, and student voice are captured in the comprehensive career plan that career practitioners develop with students. The student and career practitioner work together. The primary focus of this relationship is to help students gain clarity about their career goals while aligning those goals with their interests, skills, and the current job market. As the student-career practitioner relationship is self-selected and not assigned or forced, the connection organically evolves into a productive, co-created partnership.

A career practitioner’s obligation is to help students develop self-efficacy.8 Student self-efficacy emphasizes a student's belief in their ability to control themselves and their circumstances to accomplish a task, goal, or plan of action. Career services professionals encourage students to develop skills such as leadership, effective communication, and professionalism that promote self-efficacy.9 Specifically, the more students serve in leadership positions, practice mock interviews, attend career fairs, immerse themselves in internships and experiential learning, and connect with other students through clubs and organizations, the greater their capacity to achieve self-efficacy. The role of career services is to fortify student self-efficacy by creating a safe and nurturing counseling and coaching space to assist students with building their capacity to attain success in the world of work, hopefully, with a balance of future job satisfaction and healthy lifestyle habits.

Modern-Day Career Practice

Statistically, 72% of education professionals believe that it is their responsibility to prepare students with the right skills to be successful in work.10 Current career centers are systematically designed to be transactional. As a result of commonly understaffed university career service centers and the norm of inordinately high career counselor to student ratios, there is a limited supply of career practitioners available to meet the large demand for their services by students, alumni, faculty, and the university community. Consequently, career counselors must engage with students in a routinized manner. A checklist of “must do’s” anchors the counselor’s engagement with the student. The career counseling appointment is traditionally focused and quick, usually lacking any warm connection. Considering students’ needs at this critical stage in their life, the essential elements missing in the exchange are relationship building and time.

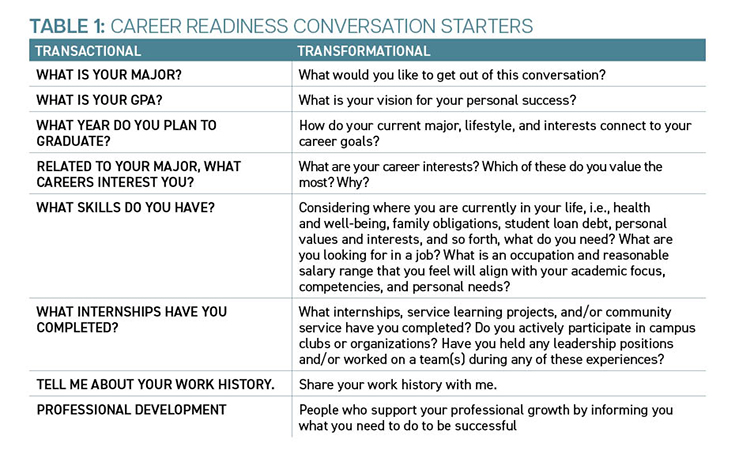

Compared to millennials and prior generations, Gen Zers are different in how they think and learn. Gen Zers need to trust and feel safe with individuals before they connect with them. Accordingly, building relationships with Gen Zers is critical to collaborative engagement. As relationships take time to build, creating connections with students must honor the need for time and space. Career advisers and career coaches take a deeper look at an individual’s life as a whole. Through career advising and coaching, career practitioners can invest the time to transition students to the world of work. This transformational process is paced by student need, which is determined by the student’s educational background, life experiences, interests, and aspirations. To accomplish this, career practitioners can employ a variety of best practices, including career assessments, SMART goals, a career plan, skills-building, resume and interview preparation, mock interviews, networking, continuous learning, insight on healthy and productive social media engagement, and referral(s) to additional support services. Critical to the college-to-career journey for students is emotional intelligence. Accordingly, students desire to engage in realistic conversations with career professionals where their voice matters and the coaching conversations are infused with encouragement and hope throughout the experience. (See Table 1 for prompts in a transactional discussion versus those that are characteristic of a transformational exchange with students.)

Career Services: Response to Student Need and Relevance

Between 2016 and 2019, career services at Rowan University provided the On the Spot (OTS) program—an example of a transformational offering. Fondly referred to as “taking it to the streets” by the career services staff, this program was established to bring in-person career services to the students instead of waiting for students to come to the office or to schedule an appointment through the digital scheduling platform. In collaboration with the individual colleges, there were career services “pop-up shops” regularly happening across the campus.

OTS, developed by Shirley Farrar, one of the authors of this article, focused on reaching students and meeting them where they are to familiarize them with the career services center and provide them support they often didn’t realize that they needed. Career counseling, resumes critiques, and brief mock interviews were provided, information was shared, and most importantly, relationships were built with students.

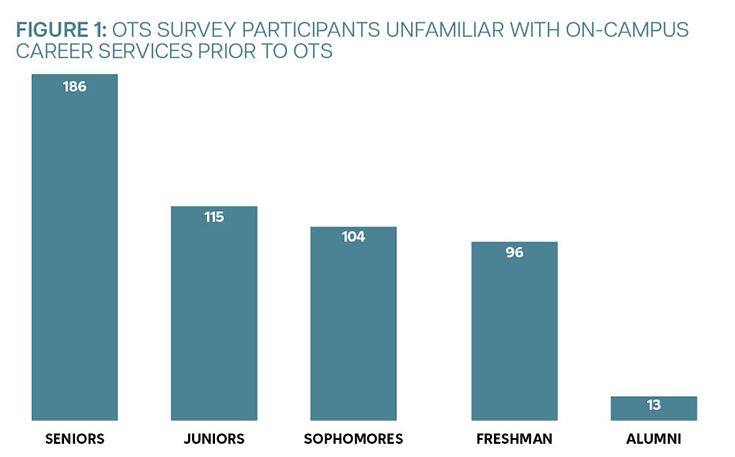

Data collected from 2016 to 2018 among students taking part in OTS, found that 514 of the 856 students completing the survey were unaware of/had not used the campus career center prior to their engagement with OTS, including nearly 200 seniors. (See Figure 1.) Among responding seniors, 78% said they took part in a resume critique through OTS.

OTS translated into other career engagement events for students and alumni. For example, through OTS, the first Science Industry Fair was hosted in 2018. A successful collaboration with the college dean, faculty, student organizations, and the academic adviser yielded an event that attracted 200 science students who had the opportunity to meet with 14 employers. Employers provided scheduled informational sessions and interviews for internships and job openings. In addition, OTS’ end-of-the-year barbecue, a collaboration among the career services and employer relations teams, the Office of Student Enrichment and Family Connections, various Divine 9 sororities and fraternities, employers, and community organizations, provided a creative outlet for outreach, which netted approximately 500 student participants.

Although OTS was discontinued due to a shift in administration and the pandemic, OTS programming and partnerships set a precedent for future career services programs and marketing at Rowan University.

The Significance of Transformational Career Practices

How does transformational career counseling position students for success?

Transformational career services acknowledges the following priorities: 1) Student identity and cultural background; 2) student interests and aspirations; 3) student voice; 4) connections and relationships; 5) generational shifts; 6) optimization of time; and 7) co-created intended outcomes.

As noted by Farouk Dey and Christine Cruzvergara, the transactional career services approach must move toward a transformational model.11 Both contended that university leadership must fully understand and respect the needs of all students, and career services leadership must be well-informed and equipped to provide customized advice, research-based strategic initiatives, and student and alumni career readiness skills to successfully launch our students into the world of work.12

This perspective suggests that innovative programs that are significant in impact and yield student buy-in—as was the case with Rowan’s On the Spot program—should not be viewed as a one-off or too unconventional. Instead, career services programs that have a proven track record of success with students should be endorsed and consistently supported.

According to Gallup, students do better in their transition to the world of work when they are career ready.13 NACE defines career readiness as “a foundation from which to demonstrate requisite core competencies that broadly prepare the college educated for success in the workplace and lifelong career management.”14 More broadly stated, career readiness is the process of preparing students of any age with the competencies and skills they need to find, acquire, maintain, and grow with a career.15 Accordingly, the success of the On the Spot program and programs like it should be the impetus for an intentional transformational shift in career services. More of the same gives more of the same. To be relevant means that the status quo must shift. Masterful student engagement with emotionally intelligent career professionals and creative, innovative services and programs facilitated by career experts must become the new normal.

Endnotes

1 Pew Research Center. (2010, February 24). Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved from www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/.

2 Auter, Z., & Marken, S. (2023, September 21). One in Six U.S. Grads Say Career Services Were Very Helpful. Gallup. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/199307/one-six-grads-say-career-services-helpful.aspx.

3 Falcon, L. (2015, June). Breaking Down Barriers: First-generation College Students and College Success. The League for Innovation in the Community College. Retrieved from www.league.org/innovation-showcase/breaking-down-barriers-first-generation-college-students-and-college-success.

4 Monroe, A., & Peterson, J. (2020, August). Affirming Student Success: Reimagining Recruitment, Resilience, Retention, and Career Readiness. NACE Journal. Retrieved from www.naceweb.org/diversity-equity-and-inclusion/best-practices/affirming-student-success/.

5 Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (10th ed.). Bantam.

6 McCleod, S. (2024, February 1). Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory in Psychology. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html.

7 Ibid.

8 Springer, S., Cinotti, D., Moss, L., Gordillo, F., Cannella, A., & Salim, K. (2015, October). Fostering School Counselor Self-efficacy Through Preparation and Supervision. Vistas Online. Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/publication/327871078_Fostering_School_Counselor_Self-Efficacy_Through_Preparation_and_Supervision.

9 NACE (2024). Competencies for a Career-Ready Workforce. Retrieved from www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/.

10 Pew Research Center. (2016, October 6). The State of American Jobs. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved from www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2016/10/06/the-state-of-american-jobs/.

11 Dey, F., & Cruzvergara, C. (2014). Evolution of Career Services in Higher Education. NACADA. Retrieved from https://nacada.ksu.edu/Portals/0/Clearinghouse/advisingissues/documents/Dey%20Cruzvergara%202014.pdf

12 Ibid.

13 Busteed, B. (2014, February 25). Higher Education’s Work Preparation Paradox. Gallup. Retrieved https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/173249/higher-education-work-preparation-paradox.aspx.

14 NACE.

15 Everfi. (n.d.). What Is Career Readiness and Why Is It Important? Everfi. Retrieved from https://everfi.com/k-12/what-is-career-readiness-and-why-is-it-important/.