NACE Journal / Summer 2024

From a young age, we begin to understand what “career” means based on the people in our lives. Through observational learning, “the process of learning by watching others, retaining the information, and then later replicating the behaviors that we observed,” we form ideas about their careers.1 We then continue to frame our understandings of career, and what options are available to us, based on the experiences of those we know.2

Disadvantaged by a Smaller Social Circle

Unfortunately, the challenge for many first-generation college students is that their opportunity to observe diverse careers, including careers requiring a college degree, might look very different compared with that of their peers. Research has shown that “Americans without a college education today have experienced a much more dramatic decline in the size of their social circle than have those with four-year degrees.”3 When their parents have a smaller social circle, it limits the opportunities for first-generation college students to observationally learn about different careers and form professional connections with those who also earned college degrees. This lack of a social network puts first-generation students at a disadvantage compared to their peers whose parents completed college and could have a stronger social circle of friends and colleagues who completed, at a minimum, their undergraduate education. When networking is a key part of professional development, it is detrimental when “the networks of first-generation students are less varied, particularly in terms of including individuals relevant to college and professional development.”4

The lack of a social circle, and thus a weaker career network to support them, is not lost on first-generation students and is perceived as a career barrier. Compared to non-first-generation peers, “lack of social support and lack of time and financial resources for advanced training in the process of exploring future careers” are significant career barriers for first-generation college students.5 In a 2015 study, one described their experience: “I went to an academic adviser and I needed an internship, and they said something like, ‘Oh you know, go get your parents, friends’ and I am like, [other group members voicing agreement] ... I mean, I am at a loss, where for other people, their dad can just call up someone.”6

The inability to access the same resources and network of their non-first-generation peers can also impact their confidence in building a strong professional network. Another student in the same study expressed how they need to work harder to reach their career goals because they do not have an established professional network: “It’s kind of scary a little, because you can make your own connections, but then it’s kind of worrisome I guess that *sigh* there’s other people that have that [network], and you’re just like ‘No, it’s OK because I’ve done this, like getting here and everything and that worked out,’ but for me, I know that I’m going to have to push more and work harder and be better because I’m not going to have help like that.”7

To increase first-generation college students’ college persistence, it is important for higher education to help bolster their social capital.8 This is not only critical for their long-term success related to finding a career worth having, as they define it, but to acknowledge that an unequal distribution of social capital contributes to lower college completion rates among this student population.9

The challenge of how to increase first-generation college students' social capital, as can be seen by research going back more than 30 years, could benefit from new strategies. One newer approach, to help these students level the playing field in the career search, is to strategically use artificial intelligence (AI) tools to help bridge the gap in their professional network.

Using AI Tools to Level the Playing Field

The landscape of higher education continues to change, which means professionals need to update practices to meet students where they are. Gen Z students believe higher education needs to incorporate AI “as a tool to support and instruct students, particularly low-income and first-generation college students during their college careers and as a part of the curriculum so students are more attractive to employers and prepared to use AI in their work lives.”10 This support is also echoed by educators who believe AI can benefit students by “providing them with more efficient and effective ways to work, learn, and communicate”.11 Instead of shying away from AI and AI technologies, it is beneficial for students to develop skillsets using AI to support their long-term career goals.

AI can be used to research multiple aspects of the career exploration and job-search process. To mimic a career network, students can use AI prompts to learn about the careers they do not already have access to within their current network. One powerful way students can use AI is to gather valuable information about a career title across multiple postings by quickly identifying the main skills and attributes needed for a particular job.12

Although engaging in informational interviews with professionals in the career a student is interested in is ideal, using the following prompts can help them bridge a gap in the networking process:

Learning about a career or job:

- Provide the tasks and responsibilities to be completed as a [career title].

- I’m interested in becoming a [career title]. What are the top five skills I need to develop to succeed in this career?

- Follow-up question: As an undergraduate college student, how can I gain experience developing [one of the top five skills]?

- I want to become a [career title]. What are the educational requirements for this job role?

- Using this webpage [insert university organization website link], which organizations would help prepare me for a career as a [career title]?

Conducting industry research:

- I’m beginning to search for entry-level positions as a [career title]. Can you share three companies in [location/region/city/country] that hire for this role?

- I am interested in working as a [career title] for [company name]. What are five other companies that hire for similar positions?

- I want to work for [company name]. What are the top three attributes they look for in candidates? Pull information directly from their website.

- I have applied for a company in [industry]. What are the biggest opportunities and threats in [industry]?

- What is the average entry-level salary for a [career title] in [area/location]?

Job-search support:

- Searching this website [insert link], provide key skills, tasks, and qualifications for [career title].

- Based on my [insert degree name] degree, suggest relevant jobs I can apply for in the [insert city] area.

- Pretend you are an applicant tracking system. Review this job listing [insert link to webpage]. Extract important keywords from this job description.

Interview preparation:

- I am interviewing for a position as a [career title]. Give me a list of the most common questions asked in an interview for this position.

- What are five questions I can ask in an interview in [field/industry] that will give me insight into the company’s culture and commitment to equity and inclusion?

- I have copied and pasted my resume below. How should I describe my past work experience in an interview for a job as a [career title]? [Copy and paste relevant resume experience.]

- Give me examples of how I can demonstrate leadership experience in an interview for a [career title].

- Informational interviews: Write a one paragraph email asking a [name of your university/college] alumnus working in [field] for an informational interview.

An Activity to Help Students Build Confidence

As shown in the student story shared earlier, a weak professional network can impact a student’s confidence. We already know from instructional design and educational research that if “learners feel as though they won’t be able to accomplish their goals, then this will reduce their motivation.”13 To increase a student’s confidence, we need to help them facilitate self-growth by taking small steps forward and giving them some control over the process.14

One activity career education professionals can lead students through is helping them identify their professional network team. Instead of focusing on only one person or one role model within their network, the student can consider everyone who supports their overall success.

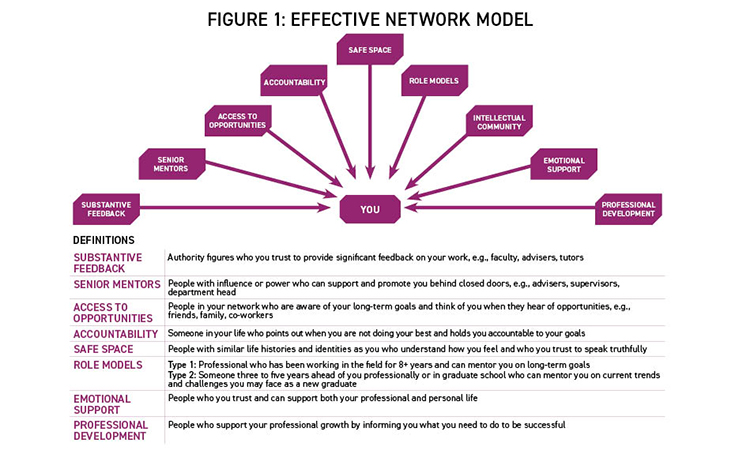

Using the Effective Network Model, explain to students each of the nine categories of an effective mentor network. (See Figure 1.) Ask them to take five to 10 minutes to identify people they know for as many categories as possible. The people they select can be individuals they already have a relationship with or someone they have in mind. One person can connect to multiple categories, but one individual should not represent every category.

After students have completed the activity, take time to celebrate with them all the wonderful people they already know or think could be a part of their network. Remind them that everyone has a network because a network includes their family, friends, coworkers, teachers, classmates, and so forth. This shows them the small steps they have already taken to be successful in relation to their professional growth.

The next step is to remind students that it is normal to not have each category of their effective mentor network filled in. To give students control over the process, ask them to set a goal of one person to reach out to in the next 30 days to help strengthen their professional network. Encourage them to use the AI prompts to help them expand their network and fill in the categories within their networking team they want to strengthen.

***

While AI technologies and tools cannot replace the value of personal connections, using these resources can help students create a stronger foundation for sustained career success in a rapidly changing future of work. Proactively using AI to strengthen their career development will help students fill in the gaps of their professional network.

Endnotes

1 Cherry, K. (2021, April 28). How Observational Learning Affects Behavior. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from www.verywellmind.com/what-is-observational-learning-2795402.

2 Nester, H. (2022). Infusing Career Into the Curriculum and the Problem of Indecision. In M. V. Buford, M. J. Sharp, & M. J. Stebleton (Eds)., Mapping the Future of Undergraduate Career Education (pp. 200-216). Routledge.

3 Cox, D. A. (2021, December 13). The College Connection: The Education Divide in American Social and Community Life. The Survey Center on American Life. Retrieved from www.americansurveycenter.org/research/the-college-connection-the-education-divide-in-american-social-and-community-life/.

4 Schwartz, S. E. O., Kanchewa, S. S., Rhodes, J. E., Gowdy, G., Stark, A. M., Horn, J. P., Parnes, M., & Spencer, R. (2018). “I'm Having a Little struggle With This, Can You Help Me Out?”: Examining Impacts and Processes of a Social Capital Intervention for First‐Generation College Students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(1-2), 166-178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12206; Jenkins, S. R., Belanger, A., Connally, M. L., Boals, A., & Duron,K. M. (2013). First-generation Undergraduate Students’ Social Support, Depression, and Life Satisfaction. Journal of College Counseling, 16, 129–142; Nichols, L., & Islas, A. (2016). Pushing and Pulling Emerging Adults Through College: College Generational Status and the Influence of Parents and Others in the First Year. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31, 59–95; Rios-Aguilar, C., & Deil-Amen, R. (2012). Beyond Getting In and Fitting In: An Examination of Social Networks and Professionally relevant social capital among Latina/o University Students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 11, 179–196.

5 Toyokawa, T., & DeWald, C. (2020). Perceived Career Barriers and Career Decidedness of First‐generation College Students. The Career Development Quarterly, 68(4), 332–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12240.

6 Tate, K. A., Caperton, W., Kaiser, D., Pruitt, N. T., White, H., & Hall, E. (2015). An Exploration of First-Generation College Students’ Career Development Beliefs and Experiences. Journal of Career Development, 42(4), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845314565025.

7 Ibid.

8 Schwartz, S. E. O., Kanchewa, S. S., Rhodes, J. E., Gowdy, G., Stark, A. M., Horn, J. P., Parnes, M., & Spencer, R. (2018). “I'm Having a Little struggle With This, Can You Help Me Out?”: Examining Impacts and Processes of a Social Capital Intervention for First‐Generation College Students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(1-2), 166-178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12206.

9 Schwartz et al.; Guiffrida, D. (2006). Toward a Cultural Advancement of Tinto’s Theory. The Review of Higher Education, 29, 451–472; Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2011). A Social Capital Framework for the Study of Institutional Agents and Their Role in the Empowerment of Low-status Students and Youth. Youth and Society, 43, 1066–1109; Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd ed). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

10 Wilson, J., Ferrer, S., Burchfiel, S., Coplon, J. M., Ashton, E., & Verdiyan, A. (2024, April 10). What Gen Z Thinks About AI in Higher Ed. BCG Global. Retrieved from www.bcg.com/publications/2024/gen-z-and-ai-in-higher-ed.

11 Atlas, S. (2023). ChatGPT for Higher Education and Professional Development: A Guide to Conversational AI. DigitalCommons@URI. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cba_facpubs/548/.

12 Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2024, April 25). An In-Class AI Exercise to Help Your Students Get Hired. Harvard Business Publishing Education. Retrieved from https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/an-in-class-ai-exercise-to-help-your-students-get-hired.

13 Pappas, C. (2015, May 20). Instructional Design Models and Theories: Keller's ARCS Model

of Motivation. eLearning Industry. Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/arcs-model-of-motivation

14 Keller, J. M. (1983). Motivational Design of Instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design Theories and Models: An Overview of Their Current Status. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.