NACE Journal, August 2020

Two unique programs housed at Rowan University are designed to have a positive impact on marginalized youth by preparing for and supporting their journey to higher education and careers.

Historically marginalized students have been systematically eviscerated from higher education and, at best, held to the periphery of participation. Scholars have defined these groups as “educationally disadvantaged” because they lack the family and community resources required for them to succeed.1 Low-income African-American and Hispanic students2 are less likely to be prepared for college because they attend schools that are resource-poor and are taught by less qualified teachers.3

Within the paradigm of education, African-American and Hispanic students are underserved in the academic realm relative to white and Asian students. Along with their racial/ethnic distinctions, historically marginalized students are more likely to come from low-income households.4 These students frequently find their academic and cultural identity under attack by the persistent, dominant features encapsulated in educational institutions. Although traditional thought views “schools as the major mechanism for a democratic and egalitarian society,”5 the achievement disparity is evidence of an alienated population struggling under the weight of a tradition of marginalization.

The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that the United States will become a “diverse-majority” country—meaning that more than 50 percent of Americans will identify as non-white—by 2026.6 Schools must then respond to the changing face of America with new approaches to inclusion. The concept of the melting pot has quickly given way to the notion of cultural pluralism, which calls for an understanding and appreciation of the values of diverse groups. Cultural pluralism promotes a “mosaic,” in which each cultural group maintains its own identity, but combines with other groups to make our society a unique whole.7 Schools that embrace cultural pluralism seek to promote diversity and avoid the dominance of a single culture.

Addressing these issues becomes the culturally proficient response. Cultural proficiency is a mindset or a state of being in which an individual or organization esteems the cultures of others while maintaining appreciation of the values and views of the individual or group. As cultural proficiency is the mindset, educational equity is the process that recognizes and considers the disadvantages of students regardless of their social categorizations. Educational equity bolsters support frameworks and models designed to ensure that all students attain the same quality of education. Educators are expected to proactively take the necessary steps to level the playing field for all students by aggressively striving to ensure that every student will emerge with a high-quality educational experience. The shift starts from the “inside out,” with individuals and the organization intentionally engaging in transformational processes to effect change.8

From Transactional to Transformational

The question of how to move from a transactional college involvement to a transformational student experience is not a new one. As college and universities compete for students, providing a high-quality academic and social experience for all students is central to many conversations and integral to developing innovative strategies and approaches. The progressive demographic shift in America to a majority-minority population and the characteristics of Generation Z frame the lens of social justice, equity, inclusion, and advocacy that ground the student pathway experiences that follow.

Two programs housed at Rowan University lay the groundwork for a transformational student experience: the First Star STEAM Academy and ASPIRE. [Editor’s note: The authors created these initiatives; Monroe leads the Academy, while Peterson was the primary force behind ASPIRE. In both cases, they collaborated in and supported each other’s efforts.] Through these initiatives, beginning in middle school, historically marginalized students move from the periphery of their learning to the center of the experience. Throughout their scholarly trajectory toward graduation and a career, their voice is sought after, emboldened, and dignified as they author their story. Expanding upon the methodology of traditional pipeline programs, these educational pathway initiatives are designed to meet the needs of the whole student by mindfully integrating education and social support that builds socio-emotional intelligence and integrates self-care, well-being, and intrusive mentoring and coaching as part of the model.

First Star STEAM Academy

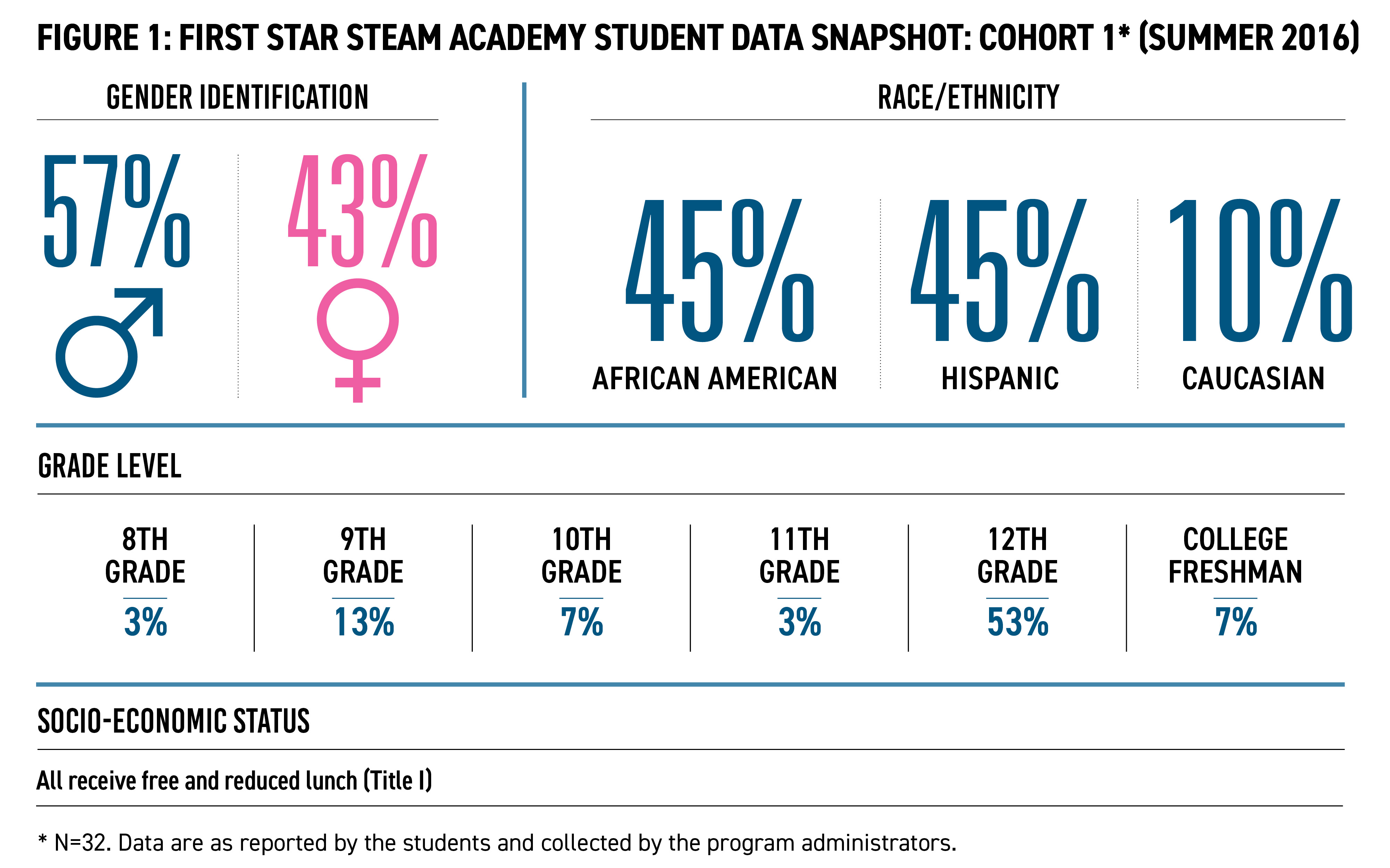

The South Jersey First Star Collaborative at Rowan University, which is funded by the Pascale Sykes Foundation, is a partnership between First Star, Rowan University, and CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocate). The Rowan Academy, implemented by the Collaborative, serves foster youth from several southern New Jersey counties.

Creating lifetime networks of support for the foster youth and their families, the Rowan Academy offers a long-term college readiness program for foster youth that includes an immersive residential summer on a university campus and monthly sessions during the school year. In an effort to ameliorate the distressing outcomes that are all too common for foster youth, the academy staff provides holistic, long-term education case management to students and their families throughout their college experience.

Understanding the inherent desire of the First Star students to dream big and achieve greatness inspired the creation of the First Star STEAM Academy in summer 2016. By esteeming their intersectionality, the First Star STEAM Academy offers a safe and trusted learning experience that cultivates student self-efficacy and progresses them toward self-authorship.

The First Star STEAM Academy, implemented in the summer of 2016 and held each summer since (including, virtually, in 2020), is an organic project-based learning model. Designed for and with the First Star students, mentors, and administrators, STEAM-related subjects anchor the core curriculum and instruction. The project-based learning (PBL) interdisciplinary approach motivates students to learn and apply knowledge and skills through hands-on experience. While students engage in rigorous critical thinking and solution building to address real-world problems, they are also developing college readiness skills and career competencies. In PBL, the role of the instructor shifts from content-deliverer to facilitator. Students work more independently and student voice drives the pace and learning process.

PBL thrusts the First Star Gen Zers into phases of self-discovery, exploration, application, and self-actualization. Student learning experiences and instruction are created using backward design, where the design process begins with a focus on the desired end results and learning outcomes. Each of the learning phases has structured benchmarks and student milestones embedded in the curriculum and pre-, mid-, and post-career assessment student data informs the decisions that instructors and mentors make with students regarding their college and career trajectory. Field experiences expose students to STEAM industries. Their discussions with professionals in these fields help them to identify the real-world problems that they tackle over the summer. Intrusive mentoring and coaching for students and mentors is also a critical element of the PBL experience. For the students and mentors that the program serves, wraparound services are integral to the First Star Academy experience.

Leading up to the summer academy, students are immersed in prerequisite learning during Saturday sessions and they participate in a service learning project. Students demonstrate the STEAM-based education and career competencies they have gained through the summer experience in their capstone project, which is presented to their families, First Star administrators, and community partners during the last summer session. This hallmark event for the First Star students has grown and evolved into a College and Career Readiness Conference, where students listen to dynamic keynote addresses; attend interactive professional learning break-out sessions; present their capstone projects; and directly engage with university faculty, career professionals, and employers throughout the day. For the majority of the students, this is the first conference they have attended.

Results and Outcomes

Ninety-five percent of foster youth that participate in the First Star Academy complete high school and attend college. Each of the students who fulfills the criteria of both the First Star and STEAM academies receives a four-year “Give Something Back” scholarship.9 The quantifiable results prove that the PBL model is a high-impact practice.

For those who work with the students, these results are humbling as we continue to channel our energy to fuel growth and improvement. For example, in response to challenges the First Star students articulated with respect to acclimating to a college campus environment and observed behaviors that warranted intervention from our mental health and social services community partners, the First Star administrative team secured an office on campus that is staffed by a First Star mentor. Students now have safe space to share, have meaningful dialogue, study, access computers, grab a snack, and get lots of smiles and First Star family love. For foster youth, who live in a world of transition, providing safe, trusted, and welcoming space is a refuge that they seek and need.

ASPIRE: Leadership Training and Skills Development

-- Briana M. Bond, ASPIRE Participation: 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011

Bachelor of Science, Marketing. Mental Health Residential Counselor, Hackensack Meridian Health

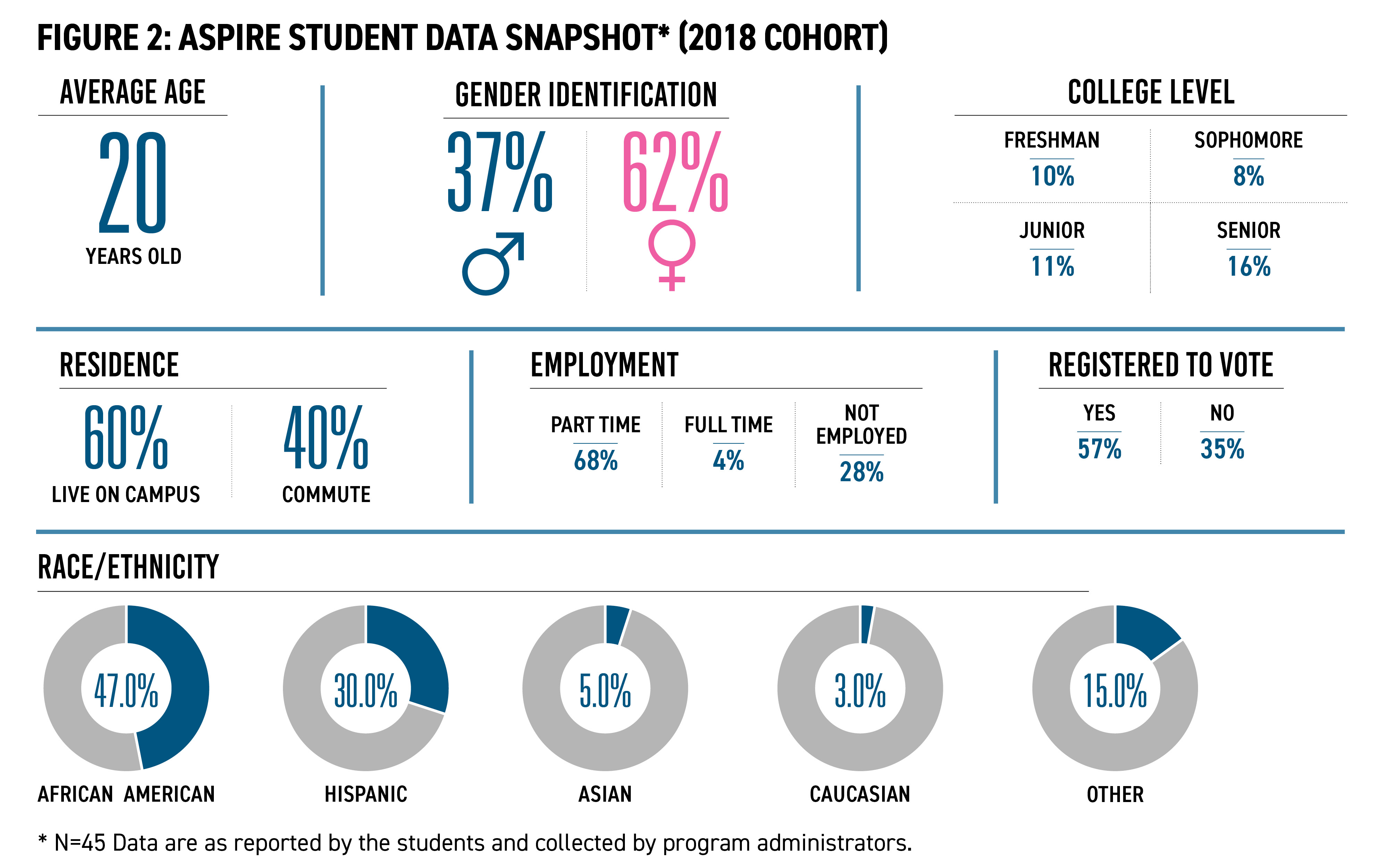

As the learning and skills development continuum progresses, many First Star students and mentors participate in the Rowan University ASPIRE (Achievement, Success and Progress Through Initiative, Respect and Excellence) student leadership experience.

Originally implemented as the Students of Color Leadership Development Experience in fall 1987, ASPIRE uses an interdisciplinary team approach to empower students academically and professionally through leadership training and skills development. This leadership experience provides students a platform for the development of academic self-concept, character building, leadership, and global/intercultural fluency.

ASPIRE identifies student leadership progression using three parameters.

- Gateway to Success: Introduces the essential skills needed for students to be academically focused, productive, and well-connected members of the Rowan University community.

- Middle-of-the-Road: Provides students, who are not yet proficient in leadership, an opportunity to acquire additional knowledge, skills, and practice. These students thoughtfully engage in self-reflection as they move toward defining their leadership identity and space.

- Peer Coach: Provides returning ASPIRE participants the opportunity to apply their leadership skills. These coaches mentor students, facilitate workshops, and lead student engagement activities.

Mirroring the world of work, students must complete a program application and formal interview to gain acceptance into the program. Accepted students are required to attend an orientation session to confirm their participation.

-- Stephen Robinson, ASPIRE Participation: 2003, 2004, 2005

M.B.S. Biomedical Science, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey; CCP, Cooper University Hospital. Staff Perfusionist, Temple University Hospital

The ASPIRE student leadership experience has launched every fall, for the past 30 years, with a leadership retreat. Each year, a new cohort of students is immersed in an interactive and engaging off-campus weekend experience that is life-changing. This transformational educational pathway experience is grounded in theory and research-based best practices. Learning outcomes are structured and clearly defined. Assessments reflect and measure the student experience. The workshops, seminars, engagement events, and social gatherings held throughout the year are driven by the student voice. With three decades of grooming leaders, ASPIRE also offers students the opportunity to tap into a well-established alumni network.

ASPIRE alumni “pay it forward” through their participation in the leadership retreat and events throughout the year. Most importantly, these career professionals partner with students as they navigate their career journey. ASPIRE alumni help students attain job-shadowing experiences, internships, and part- or full-time employment. In addition, they provide coaching for students who are considering graduate school. Since its inception, ASPIRE has cultivated an impressive group of students who have enthusiastically embraced the challenges of being leaders, change agents, and humanitarians. Motivating others by exemplifying leadership excellence, they admirably represent the ASPIRE brand in many different industry sectors. ASPIRE alumni share their stories to emphasize the success of this educational pathway experience.

There are approximately 600 ASPIRE alumni, to date. The ASPIRE legacy continues to grow and thrive as newcomers to this educational pathway experience introduce themselves to the safe, trusted learning space and commune with other promising leaders.

Hope, Promise, and Excellence

-- Kyla Fuller, ASPIRE Participation: 2015, Peer Mentor - 2016, 2017, 2018

Bachelor of Arts, Liberal Arts and Sciences, General Studies and Humanities. City Year, AmeriCorps

Asked how we continue to keep the flames of #WeAreFirstStar and #ASPIRELove lit, oftentimes we respond in unison, “passion!,” followed by “purpose.” As educators and higher education professionals, we design and map curricula, align theory with research and practice, astutely manage budget and operational obligations, balance the allocation of staff time, examine student profiles, collect and analyze student data, and more. However, upon exhausting the checklist of what needs to be done, we turn our focus to what has to be done to recruit, retain, and secure career opportunities for students. We constantly ask ourselves: What do our students need to have a meaningful student experience that positions them best for life after college?

To provide for our students’ needs, we continue to build relationships with critical partners, have courageous dialogue, listen to and accept our students’ narratives, acknowledge and genuinely celebrate the beauty of the student mosaic, and make space for new avenues of learning. Our personal truth, heart for the work; expertise; intuition; common sense; unyielding commitment; and voice of equity, inclusion, and advocacy anchor the boundless parameters to inspiring hope, instilling promise, and motivating excellence for the students we reach. The outcomes reveal that we are doing a great job! Nonetheless, at a time when social distancing; communicating with others through masks and online; and seeing traumatic images of social injustice, peaceful protests, and civil unrest is the “new normal,” we know that our work must continue to grow in depth and breadth. In light of this, we add the phrase “onward and upward” to our common vocabulary.

Endnotes

1 McElroy, E. J. & Armesto, M. (1998). TRIO and Upward Bound: History, Programs, and Issues – Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Negro Education, 67(4), 373-380.

2 Please note: The race/ethnicity categorizations used within the text are direct citations from the data sources and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the authors.

3 Gandara, P. (2002). Meeting Common Goals: Linking K-12 and College Interventions. In W. G. Tierney & L. S. Hagedorn (Eds.), Increasing Access To College: Extending Possibilities For All Students (pp. 81-103). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

4 Walpole, M., Bauer, C., Ingram, T., Kamau, K., & Toliver, R. (2003, April). Bridging the gap: Enrichment programs for underrepresented students. Paper presented at the meeting of the AERA, Chicago, IL.

5 Howard, T. (2003). “A Tug of War for Our Minds:” African American High School Students’ Perceptions of their Academic Identities and College Aspirations. The High School Journal, 87 (1), page 5.

6 Duffin, E. (2019, August 9). U.S. population by generation 2017. Statista. Retrieved from

www.statista.com/statistics/797321/us-population-by-generation/

7 Orlando, F. J., Levy, L. C., & Harris, J. L. (2003). Transition to Teaching (2nd ed.). Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Custom Publishing.

8 CampbellJones, F., CampbellJones, B., & Lindsey, R. (2010). The Cultural Proficiency Journey: Moving beyond ethical barriers toward profound school change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, page 11.

9 The Give Something Back Foundation (GSBF, www.giveback.ngo/) awards full scholarships that enable students to obtain a college degree at partner schools. The goal is to help students graduate college without debt; scholarships include tuition, room and board. Give Something Back scholars are identified in the 9th grade and are paired with trained adult mentors who help them navigate the challenges of their high school years. When these students graduate high school, they can attend one of GSBF’s partner colleges at no cost.