NACE Journal, November 2021

Obtaining a good job after graduation is the No. 1 reason first-year students give for pursuing higher education.1 However, employment statistics indicate that only 27% of recent graduates over the last 10 years report having a good job upon graduation.2 There appears to be a disconnect between first-year student goals and graduation statistics.

Although students need career readiness skills to be competitive in today’s job market, they are typically not required to visit career services at their college or university. In fact, research conducted by Strada-Gallup shows that students find career advice from faculty to be helpful and perceive their professors as experts with career planning. On average, a student will see a specific faculty member more in one week than they will see career services staff in their entire academic experience. Therefore, faculty can play an integral role in helping students prepare for their job search and succeed in the workforce post-graduation.

- Students who report that at least one professor, faculty member, or staff member has initiated a conversation with them express greater confidence that they will graduate with the skills they need to excel in the job market (39% vs. 25%) and the workplace (41% vs. 28%), and that their major will lead to a good job (57% vs. 46%).3

- Graduates indicate career advice from faculty or staff members is more helpful than that from the career services office—49% versus 30%, respectively, consider it helpful or very helpful.4

One way to address student career preparation is by ingraining career readiness skills into an activity that is required for all students: attending class.

Career services professionals know that faculty are critical resources to students both inside and outside the classroom. Faculty educate students with skills that may be applied to the workforce every day. However, through conversations with recruiters and students, the University of Central Florida (UCF) career services staff realized that our students need additional assistance in understanding how these skills can be applied to the recruiting process and workforce, as well as the ability to articulate their skills to a potential employer. The ultimate goal for both students and faculty is that students have a competitive advantage in obtaining a job.

A Program to Close the Gap Between Classroom and Workplace

In summer 2020, the UCF career services office introduced the NACE Competency Faculty Champions Program to work on closing the skills gap between the classroom and the workplace.

Syllabus Statement

This course will provide you knowledge and skills related to these NACE Competencies: [insert relevant competency/competencies]. These skills will help prepare you in securing internship or employment opportunities. This is also a great opportunity to take what you are learning in this class and see how it will help you in your chosen career!You can learn more about these competencies and how to include them in your resume at UCF Career Services: career.ucf.edu | 407.832.2362

This program was developed through UCF’s involvement with the University Innovation Alliance (UIA), a national coalition that aims to increase the number and diversity of college graduates in the United States. UCF was invited to participate in the UIA’s Bridging the Gap from Education to Employment (BGEE) initiative, which focused on college to career transitions. As part this initiative, UCF career services staff worked on various iterations of what the program could look like, and, with UIA support, decided on the specific program goals, method, and implementation for UCF.

The goals of the UCF NACE Competency Faculty Champions Program were for faculty to:

- Become familiar with the NACE career readiness competencies;

- Understand the importance of career readiness to student success, and

- Understand the important role they play in supporting students’ career readiness.

In addition, UCF career services wanted to ensure that the increased understanding among faculty was being translated to students and improving their individual career readiness knowledge and application.

A call to faculty was first sent to those teaching classes in summer 2020. Applications were collected, and participants were selected based on their plan to integrate career readiness into their curriculum, the number of students in their course, and their discipline. The goal was to impact a large number of students from a variety of majors. As of summer 2021, approximately 100 faculty and 6,000 students—mostly undergraduates—have participated in the program.

Selected faculty met with UCF career services staff in small, inter-disciplinary groups where they were introduced to the NACE career readiness competencies, a syllabus statement, and career services resources. As part of this, it was important to recognize that faculty were already providing key opportunities for students to develop the eight competencies.

During this one-hour session, faculty also shared their goals for the semester. Career services staff introduced the syllabus statement (see box), which specifically outlines the NACE career readiness competencies sought by employers and introduces students to career services; faculty could edit the statement and insert it in their course syllabus to indicate which competencies they felt their students could develop as a result of their course.

Additionally, meeting in small interdisciplinary groups allowed faculty to discuss the competencies, syllabus statement, and classroom activities as well as connect with their peers on a professional level.

Next, faculty intentionally integrated the competencies into their syllabi, assignments, and coursework.

In addition, as part of the program, faculty were required to attend an employer panel that featured four employers discussing the importance of competencies in a variety of industries. The panel discussion, held mid-semester, was recorded for faculty members who were unable to attend the live event.

Assessing Student Response to the Program

Faculty participants distributed pre- and post-surveys to their students, during the first and last week of the semester. The student survey was divided into three sections:

- In the first section, students were asked to report their demographics, including graduation year, class level, race, ethnicity, gender, and first-generation student status.

- In the second, students were asked to report their level of confidence for each of the eight career readiness competencies using a Likert scale.

- The third section of the survey focused on one competency selected by the faculty member as the primary competency covered in their class.

While they were encouraged to highlight multiple competencies in the syllabus statement and throughout their syllabus, faculty were asked to select one competency to measure their students’ ability to articulate their learning of that competency in the pre- and post-surveys. Students were asked to answer a hypothetical interview question related to the primary competency selected by their faculty.

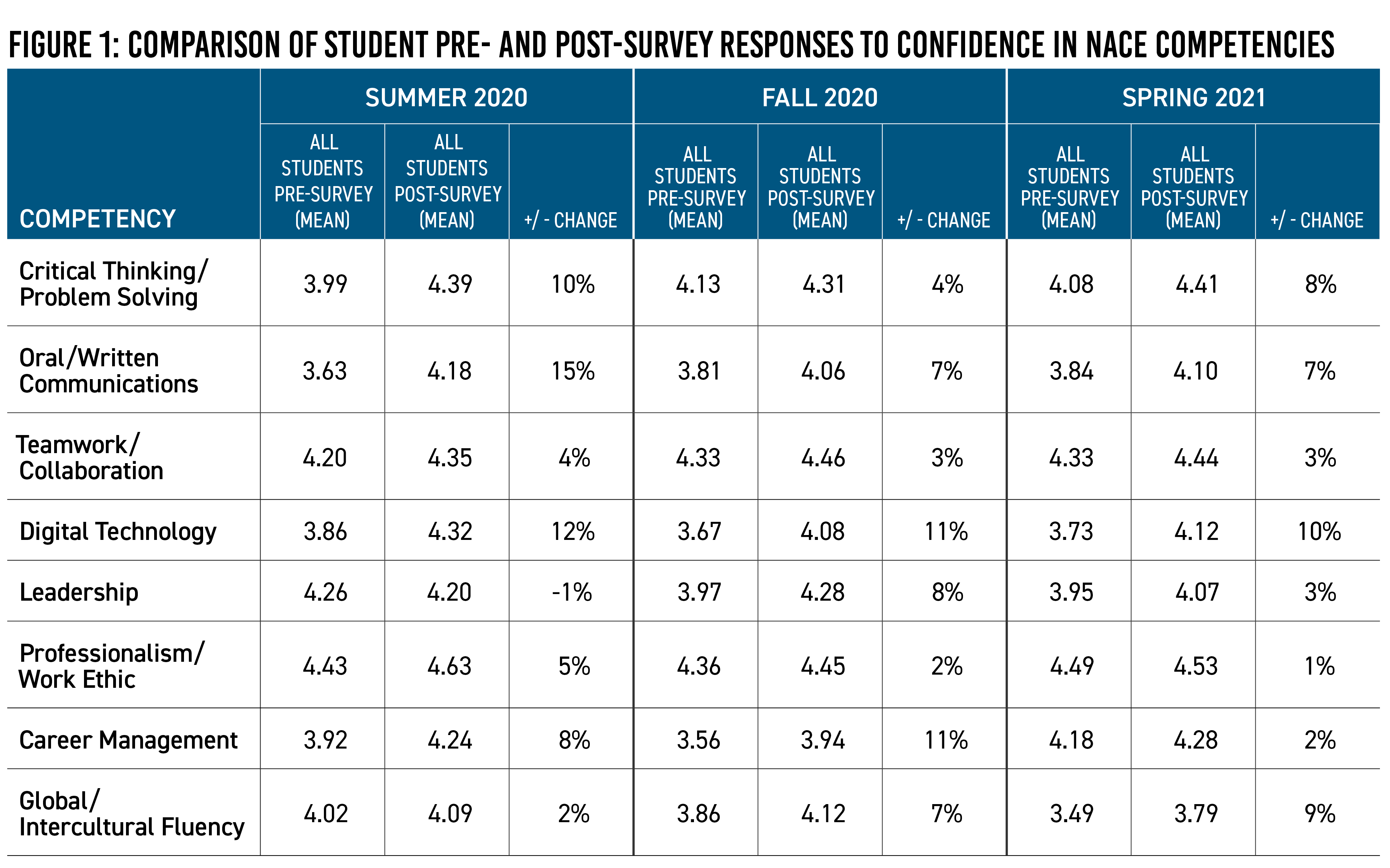

The pre- and post-survey data were compared to measure students’ increased confidence of competencies. As Figure 1 illustrates, with one exception (leadership in summer 2020), students’ confidence increased.

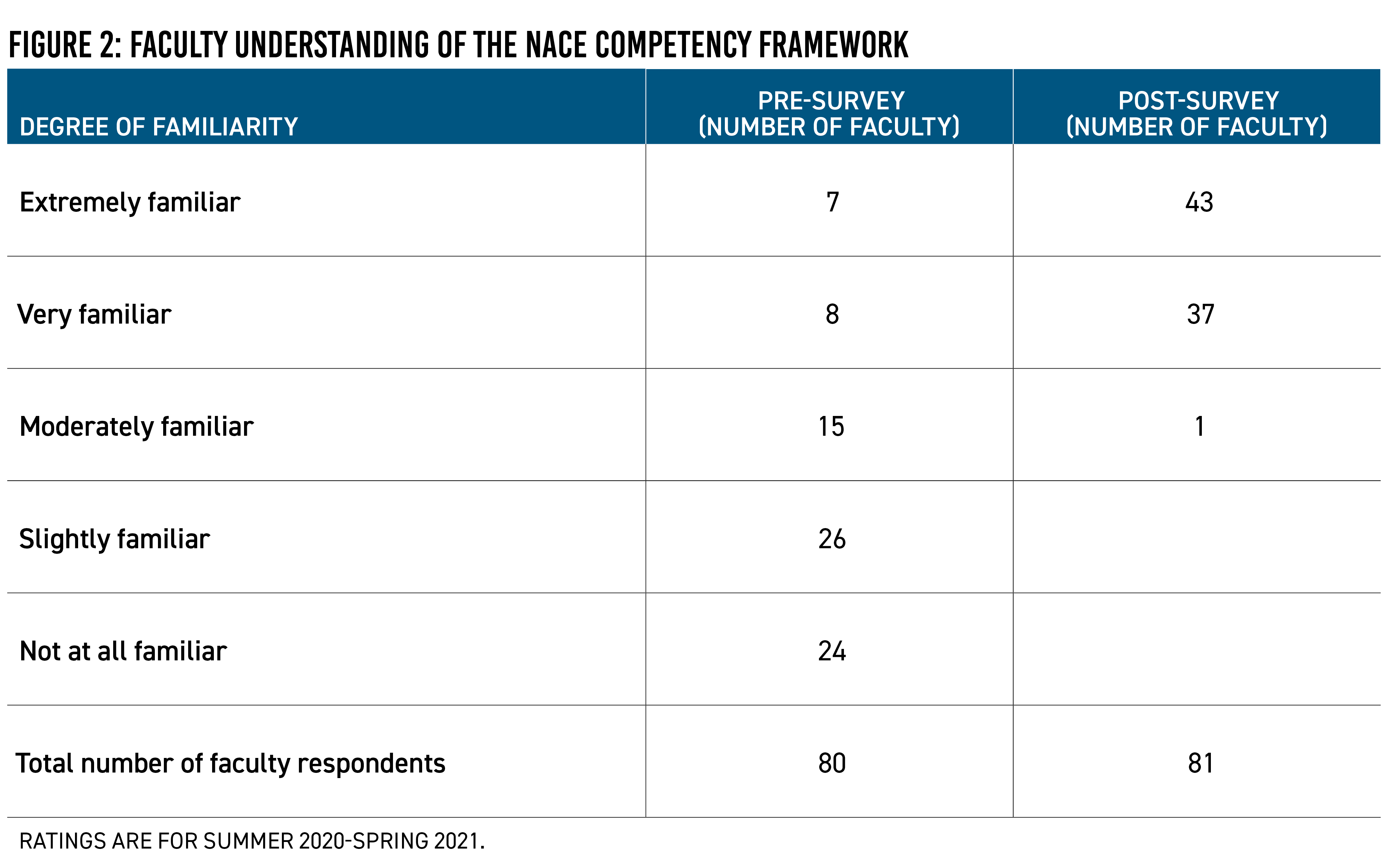

Assessing Faculty Response

Faculty were also required to complete a pre- and post-survey: Overall, their responses to the program were positive. (See Figure 2.) For example, one faculty member noted in the post-survey that “This program is a big help to our students trying to gain skills to prepare for their career. My favorite part is talking to the business representatives and learning more about what they value in the hiring process. I then pass those gems on to our students.” Another, noting the value of the program, commented that “I liked the career services support and guidance and how they connect the classes to the job market.”

The faculty post-surveys also illustrated how the program helped students understand the connection between the classroom and their future work. For example, one faculty member noted that, in their classroom, the program “emphasized the importance of professionalism and ethics to complete a group project. Many times, students complain about group work without understanding the importance of it in the workplace.”

Student Focus Groups

In spring 2021, multiple student focus groups were facilitated with the help of two part-time graduate assistants. The focus groups provided qualitative data from the student perspective on how their classes prepared them for the job search through the introduction of the NACE career readiness competencies and their improved understanding of the competencies. Recurrent themes surfaced in the focus groups that showed an understanding and awareness of communication, teamwork, and digital technology competencies.

Overall Effectiveness

Data from the student and faculty surveys and student focus groups were further collected and analyzed to review the program’s overall effectiveness.

The UCF Career Services NACE Competency Faculty Champions program allowed faculty to successfully impact the career readiness of more than 6,000 students. As a result of this program and the work of faculty across disciplines, students are now more knowledgeable about the competencies they are learning in the classroom. Furthermore, they are better able to articulate these experiences to employers.

Tools such as the syllabus statement, information sessions with faculty, surveys, and focus groups were instrumental during the implementation and evaluation of this program. Faculty were already preparing students for the workplace through a variety of assignments and activities, but surveys of the faculty revealed that this program allowed them to be more intentional in their conversations with students about preparing for the world of work. These accomplishments were possible through the collaboration between UCF career services and faculty.

Implementation Recommendations

For those interested in implementing a similar program, consider the following recommendations:

- Collect feedback on career readiness from faculty, students, and employers.

- Identify one or two career readiness goals for your campus.

- Design the program that makes the most sense for your campus; consider resources such as staff time and availability of graduate assistants.

- Promote the program through career services liaisons, on a career services faculty web page, in campus blogs, and through faculty newsletters and meetings.

- Partner with the institution’s faculty center.

- Obtain a list of faculty emails from the registrar’s office, then reach out each semester to invite potential participants.

- Enlist employers to share information directly with faculty.

- Identify faculty who have existing relationships with your office to serve as ambassadors.

At the conclusion of the program, it is important to share program outcomes and feedback with faculty. We recommend compiling and sharing data and results across campus to increase awareness of the faculty collaboration and impact on students.

In addition, be sure to champion faculty members who participated in the program by offering them digital badges or a letter of support that they may add to their CV or dossiers for promotion. We have found that faculty who participated in the program have been our best advocates.

Commitment to the Program

UCF’s commitment to the program is evident through the support of Dr. Alexander Cartwright, UCF president, who said “We now know that students need career readiness interventions early and often in their campus experience, and that career readiness must be integrated into their classroom experience and across campus.”

The UCF career services office plans to continue to grow the program by collaborating with more faculty members to bring the competencies into the classroom and impact as many students as possible. As more students become familiar with these competencies and learn how to apply their knowledge in the workplace, they will reach their goal of securing a h2>

1 Eagan, M. K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Ramirez, J. J., Aragon, M. C., Suchard, M. R., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2016). The American freshman: Fifty-Year Trends, 1966–2015, p. 70. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

2 Busteed, B. and Auter, Z. (2017, November 27). Why Colleges Should Make Internships a Requirement. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/222497/why-colleges-internships-requirement.aspx.

3 Strada-Gallup. (2017). College Student Survey: A Nationally Representative Survey of Currently Enrolled Students. p. 13.

4 Strada-Gallup. (2018). Alumni Survey: Mentoring Students to Success, p. 3.