NACE Journal, November 2018

A cross-functional team led by faculty integrated career readiness into the College of Liberal Arts at University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

The ongoing national discussion about the value of higher education, in general, and that of a liberal arts education, in particular, has been a significant challenge for liberal arts and sciences colleges across the United States. Declining enrollment and eroding public support are forcing some colleges to downsize or even shut down majors and departments, especially in the arts and humanities, or, in extreme cases, to go out of business altogether. Other colleges have concluded that to survive and thrive in this challenging environment, they need to make a compelling case for the career readiness of their graduates to their students, their families, and the public at large. The College of Liberal Arts (CLA) of the University of Minnesota is one of these colleges, and this article describes how it embarked on an ambitious project to make career readiness an integral part of the undergraduate student experience through its career readiness initiative.

A Brief History

CLA is the largest of the 18 colleges that make up the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, with almost 14,000 undergraduate and 1,700 graduate students; more than 500 tenure-stream and almost 400 non-tenure-stream faculty; and 63 majors and 65 minors in the social sciences, arts, and humanities. As with many initiatives in higher learning, CLA’s career readiness initiative originated with the appointment of a new dean to lead the college; this was John Coleman in 2014. One of Dean Coleman’s first acts after assuming leadership of the college was to appoint faculty committees to articulate a small number of goals for the college and potential ways of achieving them that would constitute a rough outline of the strategic plan for the college, also known as the Roadmap. The four goals are research, engagement, diversity, and readiness, with readiness defined as “preparing the most desirable graduates” for the job market.

To implement the readiness goal, the college appointed me to be faculty director of the initiative in August 2015. I immediately assembled a cross-functional compass team consisting of college leaders and experts from academic advising; career services; the office of diversity, equity, and access; application development; first-year experience; study abroad; honors; alumni relations; recruitment; and faculty and student representatives. This compass team was charged with operationalizing and coordinating the career readiness initiative, and met biweekly for the first two years of the initiative; it continues to meet at least monthly to this day.

Using the recommendations from the faculty committee as the starting point, the compass team defined readiness as mastery of 10 core career competencies and developed a comprehensive plan to integrate the competencies into the undergraduate experience, both curricular and co-curricular. Today, the competencies constitute a coherent and comprehensive framework that guides the career readiness efforts of the college. Specifically, for students, the competencies serve to engage them in self-directed career development and allow them to situate, plan, and understand their entire undergraduate experience in a career development context. For faculty, the competencies serve as a guide on how to incorporate the general and abstract core career competencies as learning outcomes into their teaching, and how to engage students in thinking and talking about the value of a liberal arts education for their post-graduate lives and careers. For the college, the competencies represent a coherent way to articulate the value of a liberal arts education to its various constituencies, including students, parents, alumni, and the general public.

Core Career Competencies

Career readiness, as now defined by the college, is a student’s development of 10 core career competencies. Importantly, these competencies are not specific job-related or technical skills. Rather, they represent complex and sophisticated higher-level intellectual and procedural knowledge that results from extensive and intensive engagement with one’s liberal arts education. Unlike many job or technical skills that will become outdated as technology and industries change, these competencies, provided below with their definitions, prepare students for lifelong success in their careers, particularly in a changing and dynamic future.

Analytical & Critical Thinking comprehensively explores issues, ideas, knowledge, evidence, and values before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Those competent in this:

- Recognize there may be more than one valid point of view.

- Evaluate an issue or problem based on multiple perspectives, while accounting for personal biases.

- Identify when information is missing or if there is a problem prior to coming to conclusions and making decisions.

Applied Problem Solving is the process of designing, evaluating, and implementing a workable strategy to achieve a goal. Those competent in this:

- Recognize constraints.

- Generate a set of alternative courses of action.

- Evaluate alternatives using a set of criteria.

- Select and implement the most effective solution.

- Monitor the actual outcomes of that solution.

Ethical Reasoning & Decision Making recognizes ethical issues arising in a variety of settings or social contexts, reflects on the ethical concerns that pertain to the issue, and chooses a course of action based on these reflections. Those competent in this:

- Assess their own personal and moral values and perspectives as well as those of other stakeholders.

- Integrate these values and perspectives into an ethical framework for decision making.

- Consider intentions and the short- and long-term consequences of actions, and the ethical principles that apply in the situation before making decisions.

Innovation & Creativity generates new, varied, and unique ideas, and makes connections between previously unrelated ideas. Those competent in this:

- Challenge existing paradigms and propose alternatives without being constrained by established approaches or anticipated responses of others.

- Employ their knowledge, skills, abilities, and sense of originality.

- Have a willingness to take risks and overcome internal struggles to expose their creative self in order to bring forward new work or ideas.

Oral & Written Communication intentionally engages with an audience to inform, persuade, or entertain. Those competent this:

- Consider relationships with the audience, and the social and political context in which one communicates, as well as the needs, goals, and motivations of all involved.

- Have proficiency in, knowledge of, and competence with the means of communication (including relevant language and technical skills).

- Ensure that communication is functional and clear.

Teamwork & Leadership builds and maintains collaborative relationships based on the needs, abilities, and goals of each member of a group. Those competent in this:

- Understand their own roles and responsibilities within a group, and how they may change in differing situations.

- Are able to influence others without necessarily holding a formal position of authority, and have the willingness to take action.

- Leverage the strengths of the group to achieve a shared vision or objective.

- Effectively acknowledge and manage conflict toward solutions.

Engaging Diversity cultivates awareness of one’s own identity and cultural background, and that of others through an exploration of domains of diversity, which may include: race, ethnicity, country of origin, sexual orientation, ability, class, gender, age, spirituality, and more. This requires an understanding of historical and social contexts, and a willingness to confront perspectives of dominant cultural narratives and ideologies, locally, nationally, or globally. Those competent in this:

- Understand how culture affects perceptions, attitudes, values, and behaviors.

- Recognize how social structures and systems create and perpetuate inequities, resulting in social and economic marginalization and limited opportunities.

- Commit to the fundamental principles of freedom of thought and expression, equality, respect for others, diversity, and social justice, and participate in society as conscious global citizens.

- Are able to navigate an increasingly complex and diverse world by appreciating and adopting multiple cultural perspectives or worldviews.

Active Citizenship & Community Engagement develops a consciousness about one’s potential contributions and roles in the many communities one inhabits, in person and online, and takes action accordingly. Those competent in this:

- Actively engage with the communities in which they are involved.

- Build awareness of how communities impact individuals, and how, in turn, an individual impacts, serves, and shapes communities.

- Evolve their awareness of culture and power in community dynamics.

Digital Literacy leverages knowledge of information and communications technology, and media literacies, and uses the interpersonal skills necessary to succeed in a digital space. Those competent in this:

- Assess sources of information.

- Use technologies responsibly.

- Adapt tools to new purposes.

- Keep up with the evolving technology landscape.

Career Management is the active engagement in the process of exploring possible careers, gaining meaningful experience, and building skills that help one excel after college, and lead to employment or other successful post-graduation outcomes. Those competent in this:

- Understand their values, interests, identity, personality, skills, strengths, and core career competencies.

- Are able to articulate how those characteristics, combined with and shaped by a liberal arts education, lead to career success.

The competencies by no means are completely new inventions, nor are they the exclusive domain of the CLA. Rather, they reflect the traditional strengths and values of a U.S. liberal arts education that have well-established associations with life and career success. As such, there are many similar lists that have been published by other colleges and professional associations, such as the National Association of College and Employers’ career readiness competencies or the Association of American Colleges and Universities LEAP Essential Learning Outcomes. CLA’s specific set of competencies has been developed based on a comprehensive review of these and similar existing lists of competencies, as well as on in-depth interviews and focus groups with employers, alumni, and current students and faculty. Throughout this year-long process, various competencies were identified and defined, and different sets of competencies were compared and evaluated by the compass team and faculty experts.

The ultimate set of 10 competencies was reached by consensus of the compass team with input from external stakeholders. The individual definitions were then given to a sub-committee of the compass team consisting mostly of faculty members, who further defined and operationalized the definitions, and sought additional input on the definitions from faculty in related areas of expertise. Thus, this list and definitions of core career competencies is informed by the largest possible survey of core constituencies and with significant faculty involvement to assure that not only the interests of employers and students are represented, but that the competencies also reflect the values and practices of a liberal arts institution, such as CLA.

Further evidence for how intertwined these competencies are with the teaching mission of the college is that nine of these competencies arguably represent the very essence of a liberal arts education. Career Management, the tenth competency, is an addition to the traditional liberal arts outcomes, but was judged necessary to include to assure that students understand how their liberal arts education prepares them for their future careers, provides them with practical knowledge about how to advance one’s career, and enables them to articulate their readiness for themselves, and to their families and future employers.

Integrating Career Readiness Into the College Experience

From the very beginning, it was obvious to the compass team that for the career readiness initiative to be successful, it needed to accomplish two essential tasks. First, it had to make explicit that career readiness is central to the mission of the entire college, rather than tangential. That meant that career readiness had to become the goal of all units of the college and no longer isolated within career services. Previously in the college, career preparation had been largely the domain of career services and not of academic units, with only a few exceptions. Faculty members had almost no relationships with career services and rarely were involved in offering career-related courses. Such courses typically were offered by career counselors and usually focused on nonacademic skills, such as resume writing and job-search strategies. This created a silo for career readiness within career services; it was essentially marginalized from the core educational mission of the college. To escape the silo, it was essential that the initiative was directed by a faculty member who was not part of the college administration nor the director of career services. This gave the initiative greater credibility with the faculty and also gave faculty, rather than the administration, ownership of the initiative. It also communicated very clearly to the college that career readiness is a shared responsibility that cannot be delegated to student and career services.

The second essential task was to gain faculty buy-in. As is the case in most colleges, student-focused initiatives, and really any activity by the college that is not supported by the faculty, will rarely be successful, regardless of how much support a college’s leadership and administration lend to it. Thus, achieving faculty buy-in was imperative for the initiative to be successful. To gain buy-in, faculty was heavily involved in all stages, and, in particular, in the efforts to bring career readiness into the curricula and classrooms. We achieved faculty involvement by establishing several channels for continuous communication with faculty and creating countless opportunities for faculty to assume leadership roles in the initiative, provide feedback, and interact with the compass team and the faculty director.

Most important in achieving an increase in faculty involvement, however, was the creation of a career readiness faculty fellows program that, in its first year, enrolled 24 faculty and instructors from 16 different academic units. In addition to public recognition, faculty fellows also received professional development stipends. They met regularly in small groups of four to five fellows throughout the academic year to develop and discuss teaching strategies related to the core career competencies; they also served as advocates and peer educators in their respective units. The faculty fellows program was led by a team consisting of two faculty members who are part of the compass team, teaching specialists from the university-wide Center for Educational Innovation, and a learning technology specialist, and it used a method of facilitated peer teaching. That is, faculty fellows set their own agenda and problems to work with, while the teaching team helped facilitate the discussions and brought resources to the discussions. The fellowship program ended in a mini-conference for fellows and invited guests, with the 24 fellows giving short presentations of their projects, which ranged from short in-class assignments to the development of completely new courses.

In addition, the fellowship facilitation team offered several, more narrowly focused workshops to other CLA faculty and instructors. Much like the fellowship program, the workshops focused on participation and shared ownership of learning goals and methods to emphasize and reinforce faculty ownership of the career readiness initiative. Over the course of the first year, more than 80 faculty and instructors participated in at least one workshop, and several in more than one.

Teaching & Learning Career Readiness: RATE

Fairly early, we realized that faculty buy-in and involvement alone is insufficient to effect true change in how career readiness becomes integrated into the college’s core mission of teaching. One must not and cannot assume that career readiness is automatically developed by students just because they are exposed to the competencies in the classroom. Academic subject courses rarely, if ever, explicitly focus on any of the core career competencies or on how they are used outside the academic context. Consequently, career readiness is not automatically an outcome of content learning. Rather, students develop true career readiness only through active engagement with the competencies in the form of reflective learning that is intentional and, at least initially, must be guided by instructors or the institution.

Faculty and instructors at CLA, however, had almost no experience in teaching career readiness explicitly, and only limited experience teaching it implicitly by linking course content to core career competencies. Likewise, students also had never been taught to consider their liberal arts education as preparing them for careers and, therefore, were equally unprepared to engage in the process of actively learning to connect course content to the competencies. Thus, neither students nor instructors had the training and tools necessary to successfully teach and learn career readiness. Therefore, for career readiness to become truly integrated into the college curriculum, just convincing faculty that they should teach career readiness was not enough. In addition, we also had to develop the necessary teaching methodology and tools to enable faculty and instructors to teach career readiness, and equally important, for students to learn and develop it.

The conceptual framework that describes the metacognitive process of learning that underlies the development of career readiness encompasses four crucial steps of learning: reflection, articulation, translation, and evaluation (RATE).

Reflection encourages students to think about the competencies and how they are acquired as part of the course or co-curricular experience.

Articulation allows students to talk or write about the competency now in their toolkit, and how it was acquired and used in the course or during a co-curricular experience.

Translation is the ability to take the competency outside the context in which it was learned or acquired and to deploy it in a different (often nonacademic) context.

Finally, evaluation gives students feedback on how well they are able to apply the competencies to motivate them in their learning of it; to either deepen their development of a competency or to focus their energies on another competency to be developed. While reflection and articulation are frequently employed teaching techniques by faculty and instructors to aid student learning, translation, especially to nonacademic contexts, is not usually part of instruction at liberal arts colleges. Similarly, while evaluation of how well students acquired content-level knowledge is typical in college courses, evaluation of more abstract learning is far less frequent. Consequently, faculty do not have a lot of experience in how to assess and evaluate student development in this area.

In addition to developing the metacognitive learning process that is described in RATE and taught to faculty in the faculty fellows program and career readiness workshops, we decided that we also needed to create a tool for students that allows them to engage in the active learning that develops career readiness independent of their professors and instructors. In fact, we started with the idea that students, rather than faculty, should guide the process of career readiness and that, with the right tools, students could even come to learn how their liberal arts education advances their career readiness without the active participation of faculty. We no longer believe this to be true, however. Active engagement with our students and the testing of our learning tools with students has shown that students feel overworked and pressed for time. As a consequence, a large majority of them will not engage in effortful and time-demanding activities, such as reflecting on the value of their liberal arts education, unless it is required in a course. We found this to be true even in cases where students clearly understood the value of the activity and expressed willingness to do the activity when asked. For example, since 2009, the University of Minnesota made an e-portfolio program available to all its students free of charge after a great proportion of students in surveys expressed their interest in and intention to use such e-portfolios. However, fewer than 1 percent of students actually have created e-portfolios through this service, and most of these students are doing it because it is part of a course they are taking.

The RATE tool that CLA developed is web based. Students select an experience, such as a course or course assignment for curricular experiences, or an internship or student leadership experience for co-curricular experiences. They then select one of the 10 core career competencies to RATE and are given prompts for each of the first three steps: reflect, articulate, and translate. Their responses to these prompts can be written or videotaped. Students then are presented with a questionnaire that assesses their level of achievement in the respective competency. Finally, students are presented with feedback regarding their level of mastery (novice, intermediate, advanced) and specific suggestions on what aspect of the competency they did particularly well and what aspect is most in need of improvement.

The assessments underlying the evaluation have been developed by a sub-committee of the compass team led by a social scientist who is an expert in assessment. They have demonstrated great psychometric properties, including test-retest reliability and external validity. Individual RATEs are stored and linked to student accounts, automatically creating a record for students that allows them to track their development on each of the 10 competencies throughout their college careers.

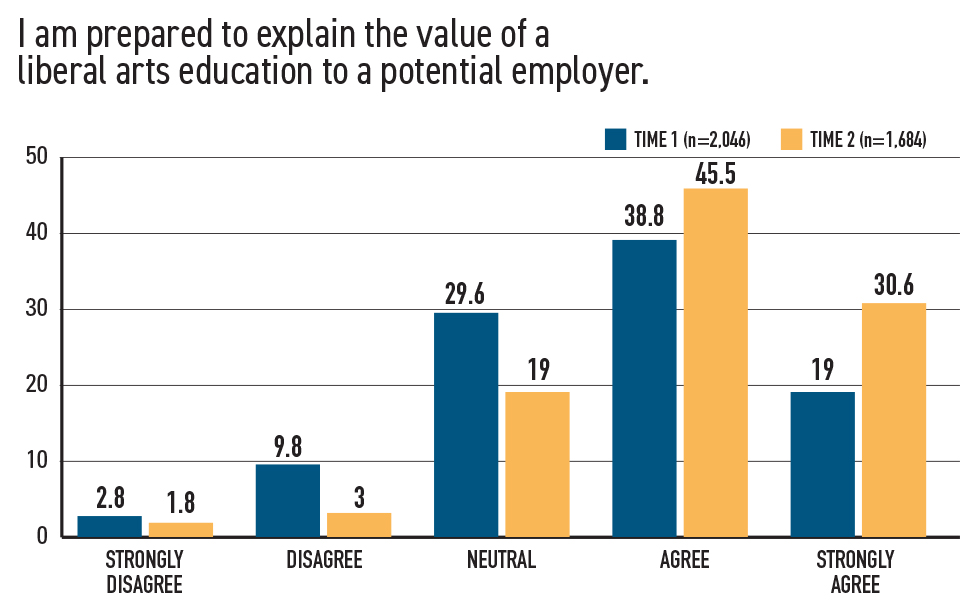

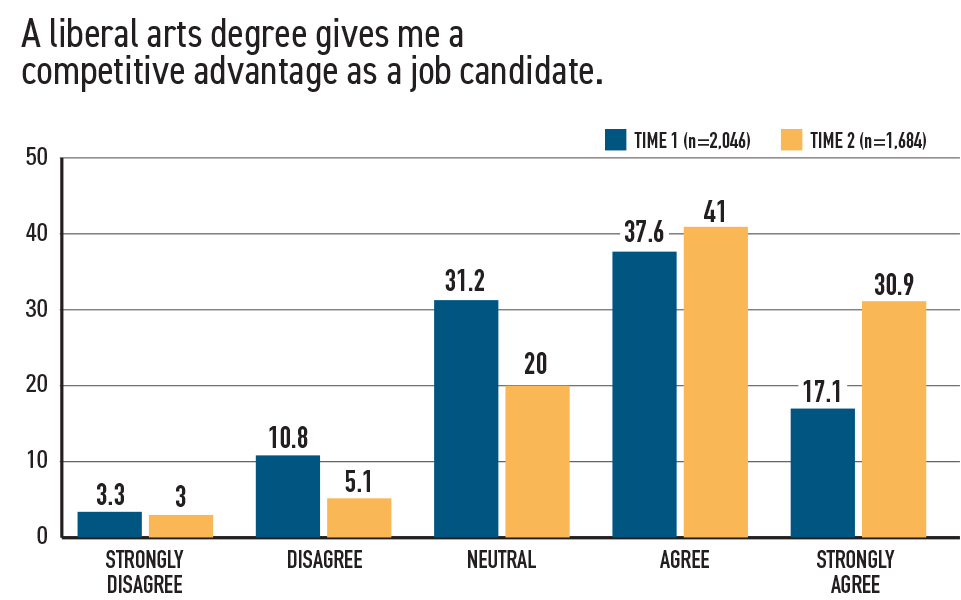

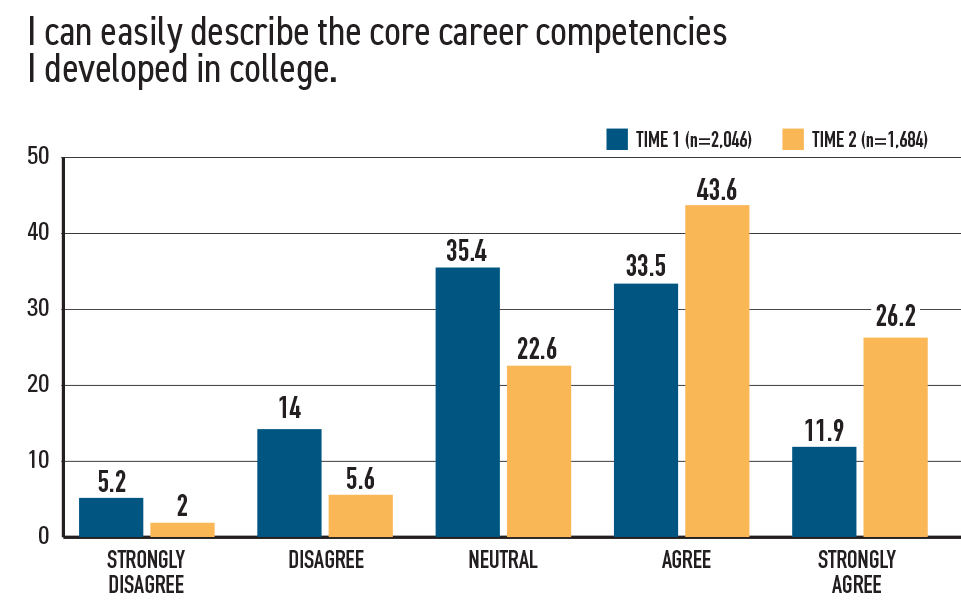

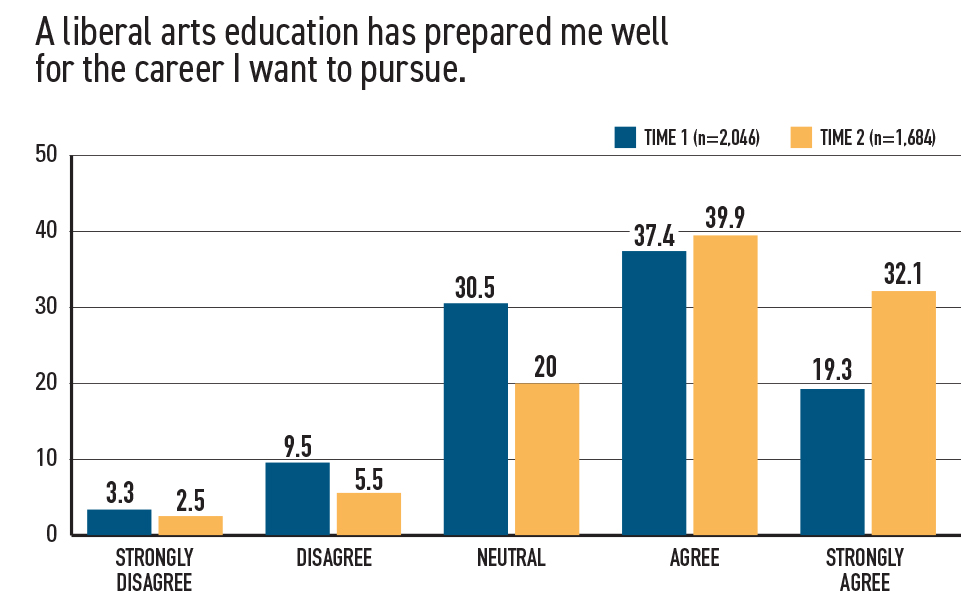

RATE has proven to be extremely effective. For example, we assigned RATE in the required first-year experience (FYE) course in spring 2018. We assessed its impact on students’ perceptions of the value of their liberal arts education and their own career preparedness within the first week of the semester (Time 1) and again in the last week of the semester (Time 2). Results showed dramatic changes in the students’ perceptions of not only their own career readiness and the value of the liberal arts, but also in their ability to communicate these to potential employers. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Changes in students’ perceptions of the value of a liberal arts education and their own career readiness (percent)

Career Readiness Everywhere

In addition to developing the RATE tool and creating faculty involvement and buy-in, a final pillar of the career readiness initiative is a comprehensive and sustained communication campaign surrounding the career readiness initiative.

To encourage students to engage in the reflective learning process necessary to develop career readiness, CLA has made significant changes in how it communicates with students about the value and purpose of their education. The emphasis no longer is exclusively on being exposed to particular content operationalized as major and general graduation requirements. Rather, similar attention is paid to the development of the core career competencies through active engagement with them. To this end, incoming students are introduced to the language of career readiness in CLA’s recruitment and admission activity, new student orientation, and required FYE courses. Student services units, such as academic advising and career services, also are using the language of core career competencies when discussing education choices and career goals with students. The college has published a career readiness guide, which has been distributed to all undergraduate students and combines an introduction to the theoretical model of career readiness and the competencies with a wealth of practical advice about resumes, interviewing, and job searching. A similar guide for internships was published and ready for distribution in fall 2018.

Likewise, faculty and academic units are encouraged to incorporate the language of core career competencies into their interactions with students and to make developing these competencies and the RATE process part of their curricula. Co-curricular and credit-bearing activities such as learning abroad and service learning also are incorporating the RATE process and the language of the competencies in their engagement with students. Finally, students can demonstrate their commitment to career readiness by earning a transcriptable career readiness certificate, the first offered by a Big 10 university.

Challenges & Lessons Learned

In principle, making an argument for the liberal arts based on how well they prepare students for their careers should be easy. However, unlike a technical or vocational education, a liberal arts education is not usually associated with particular technical or professional skills that can immediately contribute to an employer’s bottom line, so the link between the degree and employment success is less obvious. An argument for the liberal arts based on readiness, therefore, requires us to demonstrate that liberal arts education is associated with a set of competencies that are highly valued by employers that are more abstract and less immediate, but that contribute to the long-term health and success of the organization.

The greatest challenge to making this argument, ironically, comes from the faculty of liberal arts colleges. For political and philosophical reasons, they often resist an economic argument for higher education, as many of them reject the value system implied in that argument. At the same time, any change to how we educate, or even talk about how we educate, must be supported by the faculty. We found that through our RATE process, we were able to demonstrate to faculty that a focus on career readiness must not be antithetical to a focus on the liberal arts. To the contrary, by showing faculty that a focus on career readiness actually allows their students to better understand and value their liberal arts education, faculty who champion liberal arts education also champion career readiness. So, by far, the most important lesson learned is that to be successful with career readiness education in the liberal arts, the faculty has to have ownership of the initiative and ample opportunity to be heard and to impact what is done by the college as a whole in general, and by student services in particular. The second most important lesson is that you need a dedicated staff that makes it all happen.

References

Association of American Colleges & Universities: The Leap Challenge: Education for a world of unscripted problems. https://www.aacu.org/leap-challenge

College of Liberal Arts, University of Minnesota (2018). Get Ready! http://get-ready.cla.umn.edu/

National Association of Colleges and Employers. http://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/

National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Expanded edition. National Academies Press.

Zakaria, F. (2015). In defense of a liberal education. WW Norton & Company.