NACE Journal, August 2021

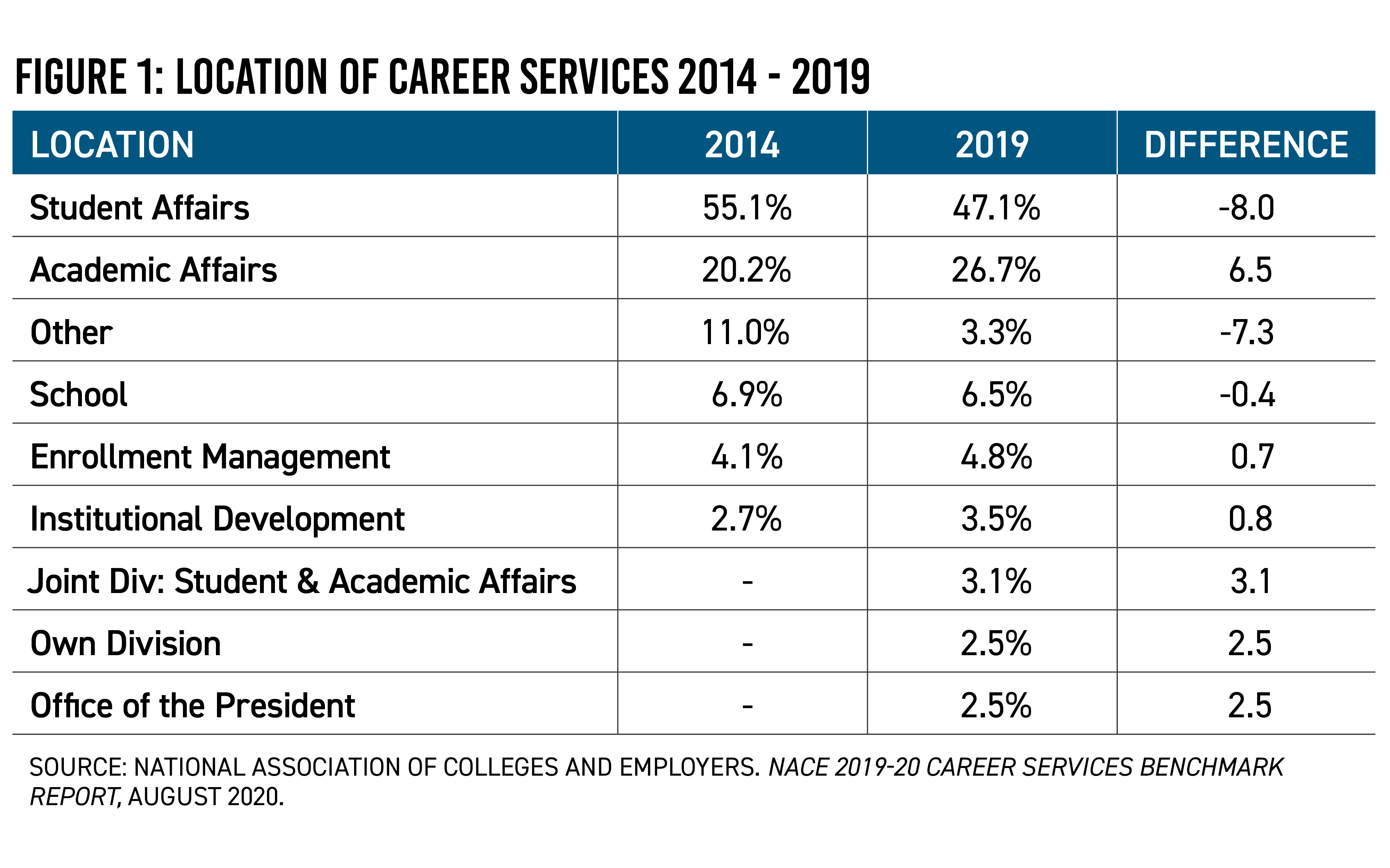

Five years of National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) benchmark data reveal that a greater number of college career services units are moving away from their traditional homes in student affairs divisions. (See Figure 1.) At the same time, their administrative destinations are becoming more diverse.

Why is the relocation of career services happening, and what does it mean for college career services units, their partners, and campus leadership?

This article explores the root causes behind these trends and presents a case study to illustrate what this shift might mean for universities exploring career services realignments on their campuses.

Career Services Is More Important to Colleges Than Ever

According to a 2018 Strada-Gallup report, the vast majority of students cite jobs and career outcomes as the number one reason for going to college. 1

The movement of career services units to a more diverse set of administrative units underscores the evolution in how career services is being viewed and valued—not only by students but by college leaders as well. This is particularly noticeable in the emergence of freestanding career services units, which presumably report to top institutional leadership, and those that are housed with the institution’s president. What is causing this evolution and elevation? While circumstances vary from campus to campus, there are three common motivations that surfaced during our research for these changes.

1. Increased demand for institutional accountability: The rising cost of college and the increases in student debt are raising questions about the value of a college degree, and that concern is translating into greater demand for evidence of student success after graduation. Accrediting bodies as well as government agencies join students and parents in demanding transparency regarding alumni career outcomes, salaries, and student debt obligations. Popular publications make use of these data to inform their ever-popular “Top 100 Lists,” such as The New York Times “Top Colleges Doing the Most for the American Dream.” Parents and students rely on these information sources when applying for admission, and colleges and universities use them to inform program design and campus funding allocations. Forward-thinking colleges, in turn, are repositioning career centers to report to units that can raise both their profile and efficacy.

2. Growing expectations for career services across the 60-year curriculum: College career services units have traditionally focused on empowering students to attain their first career after graduation. However, careers are usually made up of a series of different jobs and roles: The first job search is rarely the last. In addition, new jobs are emerging, and job-search tools and strategies are rapidly evolving. It is no wonder that alumni and continuing education students are looking to their colleges for leading-edge professional development and career advancement support to span their years in the workforce. Colleges that respond to these needs provide valuable reasons for alumni and community members to engage with and value their campus.

Done well, career services that cover the entire 60-year curriculum—which begins with the student’s first year in college and spans their career—increase chances of alumni giving, encourage alumni to hire fellow alumni, and create a broad talent pool ranging from student interns to executive-level professionals.

The shift away from student affairs, which tends to focus on the success of enrolled students, can be partially explained by the expansion of the scope of career services’ constituents, from undergraduates who look for entry-level positions to seasoned professionals found in continuing education students and alumni.

3. Connecting campus talent and economic impacts: Accountability shows up in another realm in the form of economic development. Colleges, especially publicly funded ones, are often required to demonstrate their impact on their region or state’s economy in accessible formats. (One such example is the January 2021 University of California Systemwide Economic, Fiscal, and Social Impact Analysis.)

A major force of economic impact is a competent workforce, and colleges provide an important source of the talent to meet workforce needs. Heightened calls to demonstrate the applied value of campuses to their local, regional, and state constituents mean that the career services function needs to be better positioned to play a key role in connecting the employer community to the campus. They also need greater capacity to quantify and present the outcomes of these efforts.

Colleges Are Signaling Change by Repositioning Career Services

The growing importance of career services is a key driver behind its new administrative alignments, and a shift away from being housed within traditional student services units is a clear trend. A review of the nature of, and dynamics between, the two sets of services indicate at least three reasons why moving away from student affairs makes sense for many universities.

1. Student affairs units have a different orientation than career services: While there are exceptions, student affairs divisions primarily exist to positively shape the experience of enrolled students by providing services that address immediate student needs, such as psychological counseling, testing accommodations for students with disabilities, student conduct issues, and, often, housing and dining. These services are absolutely critical to the successful and timely graduation of students. While student affairs units impart invaluable lessons and experiences that can last a lifetime, their focus tends to be in the here and now.

In contrast, life beyond graduation is core to the mission of career services. It can be argued that career services assessments and internships primarily help enrolled students, but it is also true that these self-discovery and capacity-building experiences are in place to facilitate smoother transitions from campus to career.

Unlike student affairs units that focus in on specific student groups, e.g., veterans or students with disabilities, most career centers are charged with serving the entire student body. In addition, they need to establish positive relationships with external groups, mainly employers. Career centers are usually not staffed to reach significant numbers of students with methods that work well for other student affairs units, such as one-on-one appointments, small support groups, and limited-capacity workshops. Even before COVID-19, many career centers markedly diverged from heavy reliance on person-to-person, in-office service delivery to the creative deployment of self-service technologies, such as online interview practice and resume review tools, to scale equitable access to quality services.

Such career services tools could be used in regular courses, making career development an unavoidable and ubiquitous part of the student experience. Having career services in a reporting line to academic affairs would ease entry of career development topics into the curriculum. That is not to say that online tools and their infusion into courses take the place of career advising professionals. As students partake in these online offerings and course assignments, they would be able to take advantage of career services primed to engage in more complex discussions, making the most of both their limited time and that of a highly trained career services advising staff.

2. Career services requires outreach to an external constituency—employers: With its emphasis on students, the typical student affairs unit can overlook the amount of work career centers do to engage the employer community in connecting with students via career fair coordination, information sessions, and effective job postings. Moreover, and understandably given its focus, the student affairs infrastructure does not have expertise in promoting services to employers. Consequently, career services units housed in student affairs are largely on their own in conducting market research into employers and undertaking outreach, relationship building, and event planning.

External marketing expertise plays a critical role in connecting employers and students, but is also imperative as many career services units depend on employer-sourced revenue to cover portions of operating costs and staff salaries. While many student affairs units are fully supported by set campus registration fees and/or known commodities—for example, a set number of beds in residence halls—career center budgets that are tied to swings in the overall economy are far more volatile, requiring complex budget and forecasting scenarios. If student affairs does not possess expertise in finance and accounting practices associated with a dependence on unpredictable external income, their career services units can struggle.

3. Student affairs and career services compete for resources: While all units on campus compete for resources—and there are never enough—career services units housed within student affairs divisions often take a back seat to those units that address immediate student crises and those focused on traditional measures of student success, such as retention and time to degree.

Moreover, the fact that a career services unit, at least in theory, has the ability to generate income from employers can compound the idea that career services need not be a high priority for the student affairs budget. However, generating income requires substantial staff time, and the income is both unpredictable and limited. Even in the best of times, companies do not allocate large budgets for participating in cost-bearing activities, such as career fairs, and these small budgets are usually spread thin across a number of college campuses. While the ability to raise income allows career centers to innovate when times are good, it comes with costs and can present a faulty justification for overlooking the career services unit’s need for support.

For these reasons and more, many career services units are either being moved or looking to move to administrative units that elevate their importance and better resource them to meet their goals.

Here, we illustrate the issues raised and the benefits realized by a radical and unique shift of reporting assignment for the former career center at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

Continuing Education and Career Services: A Unique and Natural Union

To elevate the status and importance of career services, UCI’s chancellor and provost designated the career center, which was housed within the Division of Student Affairs, a separate Division of Career Pathways (DCP) and created a new position: vice provost for career pathways.

DCP is now directed by the new vice provost and administered by an associate vice provost whose title was previously director. The new vice provost also continues to hold the title of dean of continuing education, uniting the responsibilities for continuing education and career services under one person. These changes occurred in October 2017 after an extensive six-month review by a provost-appointed committee.

The administrative union of continuing education and career services is both unique in higher education and natural as both units exist to transform lives through career advancement and professional development. No other university in the country has such an administrative structure. The union makes the Division of Continuing Education’s (DCE) considerable resources (both human and financial) available to DCP, creating a more cohesive relationship between DCE and UCI’s enrolled students, and addresses many of the issues related to placement under student affairs as explained above.

Initial Concerns and Issues

The organizational shift created immediate concerns for DCP and DCE staff. For example, because DCE was so much larger than DCP—200+ employees versus 18 employees—an overarching fear was that DCP and its unique culture would be overwhelmed and ultimately disappear. Within this general concern were several issues that had to be addressed.

Defining the new alignment

When the decision about the new union of DCE and DCP was announced, questions arose about how the two divisions would relate to one another: Does DCP “fall under” DCE, or does it stand beside it as an independent division? And, if DCP falls under DCE, can it retain a student-centered mission and independent strategic plan?

Eventually, through an organic process, we have clarified the relationship and describe it as an “administrative union,” meaning that the DCE and DCP retain separate identities, but share leadership and administrative functions like HR, business services, facilities management, marketing, and technical support. This arrangement greatly benefits both parties. The DCP and DCE are clear on their missions and benefit from cross-unit collaboration, and DCP enjoys heightened infrastructure support.

Perceived culture clash

The entrepreneurial character of the DCE, which is looked upon by some parts of campus primarily as a “money maker” instead of as a mission-driven unit, created concerns that students would begin to be charged for the career services they had been receiving for free (funded by university funds and student fees). Over time, this concern has been addressed—no new fees have been instituted or proposed, and students and employers enjoy more services than they did prior to the realignment.

Job loss and role change fears

With any change of leadership, staff members worry about their jobs and how those jobs might change. While there were changes that required adjustments, for example, DCP’s single marketing coordinator moved reporting lines to DCE’s 20+ person marketing department and DCP career advising staff now have more technologies to deliver basic services, fears of job loss have decreased.

The Benefits of Reorganization

As these challenging issues were being addressed, strong benefits of the relationship began to emerge. The following real-life examples from our experience at UCI are presented as inspiration for the modification and adoption of creative partnerships and innovative approaches.

Elevated stature and capacity

After three years, the union of continuing education and career services on the UCI campus has yielded very favorable results and increased the capacity and profile of both units. A reorientation of career services was aided greatly by the promotion of the leadership of career services to the level of vice provost and membership in the provost’s cabinet. This elevation sends a strong signal to the campus that career services is a higher priority for the campus, its students, and the external and local community.

Increased employer engagement

It is an imperative that both career services and continuing education serve the needs of employers, both in their backyards and across the globe. Traditionally, employers have looked to career services for early career talent, while they have looked to continuing education for employee training. However, when career services and continuing education team up, a university can present a powerful and comprehensive approach to meeting employers’ needs.

For instance, the union of DCE and DCP allows UCI to provide access to three talent pools: enrolled students, continuing education students, and alumni. From these three populations, employers can fill both entry-level and experienced job requisitions. On most large campuses, employers are often sent on time-intensive “scavenger hunts” to tap into the full array of campus talent. A key driver behind the partnership of career services and continuing education, as well as the Alumni Association, is to open employer access to all three populations and increase the chances of employer satisfaction and repeat business. We do this by asking DCE staff, particularly in our corporate training group, to refer their clients to DCP to learn about the variety of talent available at UCI. We also feature each unit on the other unit’s website and in collaborative programming. In addition, as more DCE students and UCI alumni engage with DCP services, they add to the spectrum of talent accessible to employers.

Leveraging marketing efforts

Both the DCP and DCE strive to reach new constituents. For example, DCE would like UCI students to know that many of their undergraduate courses count toward UCI continuing education certificates. This requires internal marketing expertise and channels, which DCP possesses. Likewise, DCP would like to bring more labor market intelligence, as well as employment opportunities, to campus, and this requires external marketing capabilities, such as sophisticated labor market research engines and advanced social media skills that DCE frequently uses. The partnership has allowed DCE and DCP to mine each other’s resources to learn about the skills our local employers value most and to cross-promote each at meetings with employers as well through each other’s websites, online calendars, social media, and newsletters.

Expanding career services with online modules

DCE’s extensive capacity to create online courses has been used in many ways to the great advantage of the campus and its students. For instance, students frequently turn to staff and faculty for career advice, but many faculty and staff do not feel adequately equipped to offer meaningful help. To address this need, we combined DCE’s instructional design capability with DCP’s expertise to launch online “Career Conversations” modules for campus staff, faculty, and student leaders. Not only do these modules instill confidence, but also they help increase DCP’s visibility and scale its services.

Collaborative module creation also serves to support the employer community. For example, DCP collaborated with DCE to create “How to Host an Intern” online modules after DCP’s Employer Advisory Board expressed a need for them. The modules help employers start and strengthen internship programs and feature a mix of video and text content as well as interactive worksheets on topics such as “writing internship objectives” and “identifying your student target market.”

Developing career services for DCE students

Before the administrative union, DCE had a small webpage devoted to career-related content for its students but did not feature any career services. However, with the accelerations of the pandemic and the increased unemployment rate, it became clear that career services needed to be a major feature of DCE’s programs. DCE engaged DCP and its leadership in developing what ultimately became a multi-tiered approach to continuing education career services, including a very extensive website of resources, career counseling, and career panels and workshops for students in DCE certificate programs. The expertise in DCP was invaluable in creating this important new service.

Building a technology suite to scale services

Technology sharing is the cornerstone of the partnership between the DCE and DCP. When DCE and DCP aligned, they formed a DCP Technology Committee that includes DCP and DCE staff as well as representation from UCI’s Alumni Association and the campus Office of Information Technology. The committee sources and vets online services that span our populations and can be intentionally infused into recruiting efforts, classes, workshops, and advising. Our approach has produced one of the nation’s most robust technology suites and has realized great outcomes that have led to continued campus support for our online delivery of services.

For example, when DCP made an AI-powered online resume review tool available, nearly 1,000 students used it within the first week of its launch. During fall 2019, more than 2,800 students used the platform, approximately equal to the number of students receiving resume feedback in drop-in appointments for the entire 2018-19 academic year. Its use continues to grow and is especially resonating in this time of COVID-19 and campus-wide reliance on remote services.

Badging in development

DCE is a leader in delivering high-quality digital credentials, i.e., “badges,” and is developing digital credentials to prepare students for the world of work. One of its first such credentials, in Excel, was identified as a skill gap by DCP’s Employer Advisory Board. Other digital credentials, covering topics such as learning to use PowerPoint, being effective in the workplace, and crafting a networking pitch, are being developed. These credentials will focus on actual skill attainment, often called competency-based assessments, rather than simple learning achievement and will require the expression of skill judged by a fully qualified assessor. The extent and use of such credentials will be a revolutionary force in career services and higher education.

Conclusion

A shift in organizational structure for career services on college campuses across the country is an indication of an emerging higher education imperative—the 60-year curriculum concept—and the important role that career services plays to fulfill that imperative. College and university administrators, as well as career services leadership, are recognizing the broader picture against which campus-based career services are viewed, and they are moving to make more effective use of most of the opportunities that expanded and elevated career services represent.

The goal of higher education is not just to educate students, but to prepare them for the world of work, success, and happiness in life. Ultimately, our success will be in the quality of internal experiences of the millions of students who go through our programs every year, a measurement that is difficult to quantify, but also highly appreciated. Career services plays a huge role in that measure—a role that is increasingly recognized and aided by repositioning where the career services unit is placed on campus organization charts.

Endnotes

1 Why higher ed? Top reasons U.S. consumers choose their educational pathways (2018, January). Insights from Strada-Gallup Poll. Retrieved from https://go.stradaeducation.org/why-higher-ed.

References

Busteed, Branden. Career services will define the next big boom in college enrollment. Forbes. December 2020. Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/brandonbusteed/2020/12/21/career-services-will-define-the-next-big-boom-in-college-enrollment/?sh=5dfd7340145e.

Matkin, G. (2020, January 6). The 60-year curriculum. eCampus News. Retrieved from https://www.ecampusnews.com/2020/01/06/the-60-year-curriculum-what-universities-should-do/2/ .

Matkin, G. (2019, April). A practical guide to issuing badges at your institution. The evoLLLution. Retrieved from https://evolllution.com/programming/credentials/a-practical-guide-to-issuing-badges-at-your-institution/ .

NACE 2019-20 Career Services Benchmark Report (2020, August). National Association of Colleges and Employers.

These three activities could help improve post-graduate outcomes (2018, August). Education Advisory Board (EAB) Blog. Retrieved from https://eab.com/insights/blogs/student-success/these-three-activities-could-help-improve-post-graduate-outcomes/.

Top colleges doing the most for the American dream (2017, May 25). The New York Times. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/05/25/sunday-review/opinion-pell-table.html.

The University of California Systemwide Economic, Fiscal, and Social Impact Analysis (2021, January). University of California. Retrieved from https://universityofcalifornia.edu/sites/default/files/economic-impact-report-2021.pdf .