NACE Journal, May 2018

With all the competing demands for our attention, it is easy to lose sight of the core relationship that drives our work as higher education professionals—the relationship between students and staff. This relationship is fraught from the start: Are students our customers, clients, or collaborative partners? If they are customers, is the customer always right? If they are clients, what obligations do we have to them? If they are partners, how do we cultivate a relationship of equals that empowers students to close that gap between where they are and where they want to be? The coaching movement generally—and career coaching with college students in particular—offer some new answers to these questions.

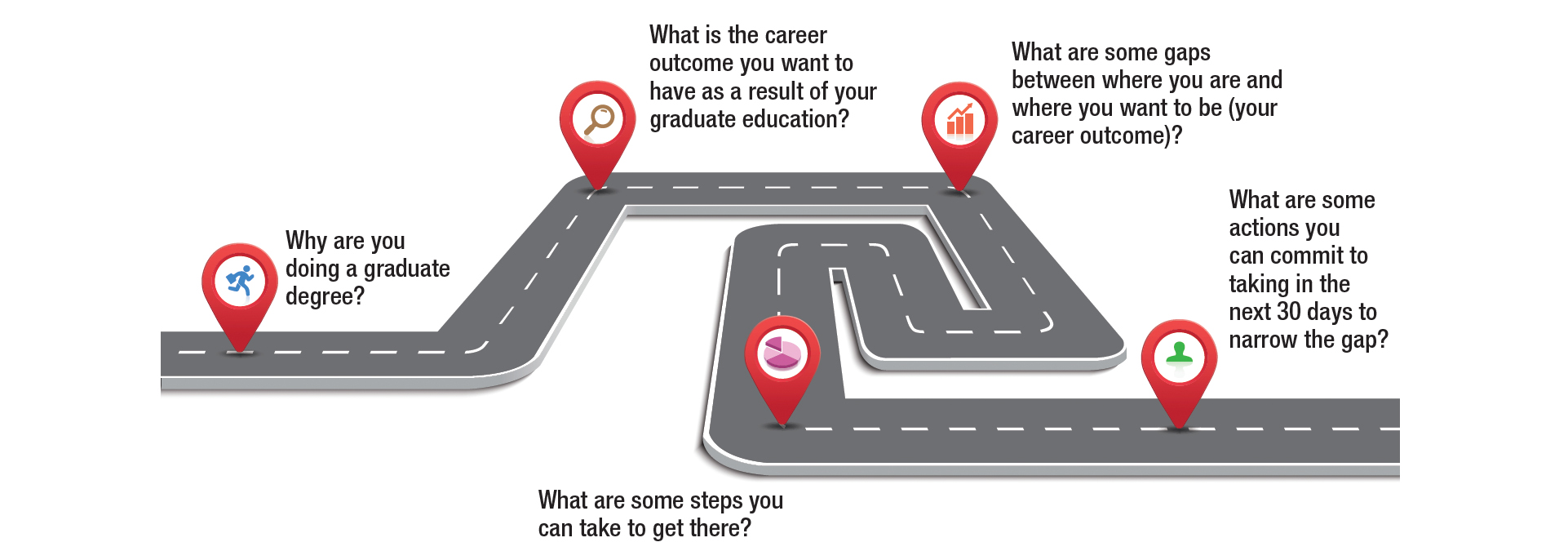

See also “Career Coaching: The Wandering Map” by Kate S. Brooks.

For those of us who grew up (professionally speaking) in the student affairs tradition of the 1980s and 1990s, our path was informed by the optimistic outlook on human development explicated by such foundational figures as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow. Remember client-centered therapy, the hierarchy of needs, self-actualization, or Chickering’s seven vectors of psychosocial identity development? Over the years, a burgeoning self-help movement, major shifts in the demographics of college students, and the rise of a professional class of student affairs professionals engendered a humanistic counseling paradigm as the primary path for our work with students.

However, much has changed in recent decades, including advances in technology and rising costs of higher education. In addition, for many students, reasons for attending college have shifted toward preparation for a rewarding career and away from the “finding oneself” ethos of past decades. At the same time, we know students place a high value on learning about things that interest them.1 Bridging that gap between wanting a successful career and pursuing interests continues to be a touchstone for our work with students as they seek that overlap among their interests, skills, and values.

Counseling and Coaching

When career coaching with college students was introduced by Katharine Brooks in a series of articles and workshops sponsored by NACE in the 2000s, client-centered counseling was the most prevalent paradigm for our work with students. In this context, it is important to distinguish coaching from counseling, not as an either-or proposition, but rather as a difference in stance or position with regard to the staff-student relationship. Figure 1 provides an overview of how the two compare and contrast.

Figure 1: Counseling and Coaching

| Counseling... | |

|---|---|

| is based on particular theoretical constructs. | |

| Coaching... | is theoretically eclectic and practical. |

| is rooted in disciplines of psychology, mental health, medicine. | |

| Coaching... | grows out of humanistic, positive psychology. |

| is focused on present to past. | |

| Coaching... | is focused on present to future. |

| requires licensing to practice. | |

| Coaching... | is not licensed, but education and training are required. |

| involves empathy, genuineness. | |

| Coaching... | involves empathy, genuineness. |

| offers confidentiality linked to licensure. | |

| Coaching... | offers no or limited confidentiality (depends on environment). |

| Counseling... | Coaching... |

|---|---|

| is based on particular theoretical constructs. | is theoretically eclectic and practical. |

| is rooted in disciplines of psychology, mental health, medicine. | grows out of humanistic, positive psychology. |

| is focused on present to past. | is focused on present to future. |

| requires licensing to practice. | is not licensed, but education and training are required. |

| involves empathy, genuineness. | involves empathy, genuineness. |

| offers confidentiality linked to licensure. | offers no or limited confidentiality (depends on environment). |

In coaching, coach and student form a partnership of equals oriented toward the student taking next steps, closing the gap between present and future state. Borrowing eclectically from a wide range of theoretical perspectives but primarily positive psychology, appreciative inquiry, and client-centered psychotherapy, career coaching offers an alternative to the traditional counseling approach to working with students.

In career coach training workshops that I’ve been a part of, we play a word association game to elicit perceived differences between the two. Typical responses for counseling included words like assessment, treatment, intervention, helping, guiding, advising, and the like. The responses for coaching typically include words like performance, motivation, problem-solving, accountability, and support. Besides highlighting differences, the exercise shakes up assumptions and stimulates exploration of career coaching as an emerging paradigm for our profession.

As noted in Figure 1, counseling tends to focus on present to past: In the counseling mode, understanding the past illuminates the present, leading to insight and change on the part of the client. Coaching focuses more on the present, discovery of possible futures, and commitment to next steps.

A reframing exercise used in the training workshop illustrates this: In this scenario, the facilitator guides participants through a two-part thought experiment based on a mildly challenging concern participants have identified for themselves. First, participants are asked several “blame frame” questions about their concern. These questions focus on the problem, what went wrong, how long it has been a problem, whose fault it is, and the like. After a brief pause, participants are asked a series of “outcome frame” questions that are positive and future-oriented, such as what do they want, how will they get it, what can they begin doing now to get it, what resources are available, and so forth. After a moment of reflection, participants often share that the blame frame questions left them feeling stuck, closed in on themselves, and unmotivated, while the outcome frame questions stimulated a sense of agency and resourcefulness. The reframing exercise, of course, is simply a demonstration, but it illustrates how coaching with a positive, future-oriented, action bias contrasts with a traditional career counseling approach that might be more typically diagnostic and biographical.

Empowering Students

Of course, shifting our stance from counseling to coaching in our relationship with students requires much more than facilitating a reframing exercise. Nevertheless, strategies like this can empower students to see new possibilities, recognize resources, and develop a sense of self-efficacy around career issues.

At the same time, the coaching paradigm challenges us to let go of our tendencies to dig into the past, to diagnose, to explain the problem, or to provide the solutions. As helping professionals, we often bring to our work our own tendencies to have the answers, to convey the “shoulds,” to feel competent or wise, and students, of course, have been conditioned by schooling to expect prescriptions, directions, and right answers. In the career coaching mode, we step out of our typical counseling role and approach the student as a resourceful partner in the process of closing the gap between present and desired future state. (See “Worksheet: Roadmap to Career Success,” for an example of this approach.) Inherent to this approach are some key principles:

- Students are resourceful.

- Coaching fosters student resourcefulness.

- Coaching is student-centered, addressing the whole person.

- The student sets the agenda for coaching.

- Coaching is a partnership of equals.

- Coaching focuses on action and change.

In this respect, career coaching provides an accessible common language for working with students that builds on the fundamentals of client-centered psychotherapy, positive psychology, and appreciative inquiry while borrowing tools and techniques from a variety of sources. To these principles, we would add the value of a positive, engaging career culture on campus where students have opportunities to practice essential career-related skills, i.e., information gathering, networking, interviewing, and so forth.

What Coaching Is Not

As we look at adopting a career coaching approach with students, it would be wise to clarify what coaching is not. For example, coaching is not the application of wishful thinking or “pie in the sky” formulations, nor is it intended to treat or paper over mental illness. It is important to note that, in higher education, career coaching with students is not intended to serve or align with the for-profit, self-help industry. It is also different from athletic coaching where the coach exercises a great deal of control and authority; career coaching with students rests on the basic assumption of the student’s resourcefulness and the partnership of equals between student and coach.

Our practice falls into that middle ground between counseling on one hand and general coaching, self-help, and related formulas on the other. The guiding principle here is to borrow and effectively apply best practices over time, being honest with ourselves and our students with regard to the services we offer in addressing student expectations in the career coaching relationship.

While career coaching is the prevailing approach taken in our career development work with students today,2 effective practice requires ongoing training, professional development, and integration of new knowledge. Career coaching is so much more than changing a staff member’s job title or position description. Ideally, the career coaching modality would be reflected throughout our organizational units, in staffing, program development and delivery, communications and marketing, event planning, and more.

What’s Ahead for Career Coaching

As the coaching movement continues to grow and more of us take on the role of career coach working with students, the challenge will be less about the distinction between counseling and coaching and more about the distinction between coaching generally and career coaching in a college or university setting. Here we might recover some of our student affairs heritage and recall our obligation to act in the best interest of the student as we foster that partnership of equals that is the hallmark of a productive coaching relationship.

Likewise, we can work to bring about changes in our organizational units and institutional settings to reinforce a career coaching mindset using positive, future-focused language that signals to students their resourcefulness to take action. We can begin by looking more closely at the policies, procedures, materials, and messages we rely on every day to assess our own level of comfort with the career coaching approach, and take steps toward professional development and skill building as career coaches. Of course, many questions and challenges remain, especially around how to best scale up career coaching to reach more students bringing, it out of the usual one-on-one (staff-student) interaction and applying it to group settings, courses, and peer-to-peer interactions. Innovative programs, collaboration across campus, and emerging technologies may offer new pathways for the scaling of career coaching in higher education.

The career coaching paradigm is not so much a break with the past, but rather an evolution of our thinking and approach to the fundamental relationship that drives our work in higher education. This relationship, between student and staff, has been defined over the decades in various ways and ranging from quasi-parental to customer-service-oriented. The career coaching approach places students and staff on the same plane and challenges us to let go of our own tendencies to have the answers or be the expert, instead empowering the student to act out of his or her own resourcefulness. In this respect, the career coaching paradigm may be ideally suited to the current landscape of higher education, where student career success is explained more by flexibility, happenstance, continuous learning, and active engagement with others than by past models of vocational guidance, placement, counseling, and networking.3

In this new era of complex and changing connections, students will benefit from career coaching given its future focus, bias toward action and change, and affirmation of students as resourceful individuals, setting the agenda for our career coaching interactions with them.

End Notes

1 Eagan, M. K., Stolzenberg, E. B., Zimmerman, H. B., Aragon, M. C., Whang Sayson, H., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2017). The American freshman: National norms fall 2016. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

2 National Association of Colleges and Employers (2018). 2017-18 Career Services Benchmark Survey Report, Figure 11.

3 Dey, F. & Cruzvergara, C. (2014). "The evolution of career services." In K. K. Smith (Ed.). Strategic directions for career services within the university setting (pp. 5-18). New Directions for Student Services, Number 148; San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

References

Brooks, K. (2011). Applying positive psychology to career services. NACE Journal, 72(1). Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Brooks, K. “Career Coaches: inspiring students to make positive career changes.” NACE Spotlight newsletter, February 2, 2007.

Brooks, K. (2005). “’You would think…’ applying motivational interviewing and career coaching concepts with liberal arts students.” NACE Journal, 65(2). Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Chickering, A. W. (1969). Education and identity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cooperrider, D. & Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: a positive revolution in change. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A psychotherapist’s view of psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Seligman, Martin E. P. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: A. A. Knopf.