NACE Journal, November 2019

There is little chance that the readers of this publication need to be convinced of the value of internships. Years of employer surveys, research studies, and anecdotal stories from students paint a positive picture of internships as an important tool in helping students get started in a career. Research has labeled internships as a “high-impact practice” that has a positive effect on learning, retention, and graduation rates.1

While the value of internships is well established, there has been some unease with the practice of unpaid internships. There is concern that unpaid internships are not an option for lower-income students, giving them fewer opportunities than their wealthier peers. There is also some evidence that unpaid internships have less direct value on career outcomes.

At Metropolitan State University of Denver (MSU Denver), pay is a practical concern for our students. MSU Denver is a comprehensive, modified open-access, public university with 20,000 undergraduate and graduate students. The student body is highly diverse in ethnicity, socio-economic background, and age, with a large number of first-generation college students. Many of our students work full time or work multiple part-time jobs just to survive.

Last fall, the university was given some funding and allowed to use the money for programs that it thought could positively impact student outcomes. It is not surprising that the internship staff took the opportunity to put together the “earn and learn” program, designed to provide an hourly wage for students doing unpaid internships. Our goal was to determine if we could increase the number of students doing internships, and, even more importantly, see if we could impact the demographics of the students doing internships.

Literature Review

In embarking on this pilot program, it was important for us to understand what research was available as well as where there were gaps. A few years ago, NACE did a call for research in this area, and several of those studies have been published in this journal. However, those studies primarily focused on the value, learning, and career outcomes of unpaid internships.2, 3, 4 There has been less discussion of the impact that lack of pay has on students deciding to do an internship.

While higher education professionals are trying to encourage students to take time for these highly impactful experiences, we also want to think about how we have been encouraging employers to provide these opportunities in an equitable way and to get creative in how to get them paid.

In their study, Townsley, Lierman, Watermill, and Rousseau noted “the introduction of internship funding for every student increases access to internship opportunities.”5 There are also findings within that study that highlight the higher likelihood of traditional-aged students whose families had gone to college taking advantage of these opportunities more frequently than first-generation, nontraditional, and/or transfer students. They also found that funded opportunities “[led to] a decline in the number of students who never completed an internship.”6 So, pay can help with increasing access, but the question is still, for whom? And how does this show up when looking at equity in those numbers?

The conversation around access to internships, especially those that are paid, also comes down to a difference in gender and economic status. For example, in an article about unpaid internships, Philip Gardner reported that “men from families with incomes above $120,000 were more likely to be in for-profit paid internships…Women from lower income families were more likely to be in internships with nonprofits and government than higher income women students. By [and] large, women from higher incomes were found in for-profit internships.”7 Gardner found that women were more likely to be in unpaid positions; interestingly, being lower income amplified that tendency.

Similarly, Mayo and Shethji noted that “the lack of affordability of both internships and, more broadly, a college education, leaves low-income students at a significant disadvantage in a competitive labor market.”8 These findings underscore the impact programs could have when institutional funding is provided for internships; such programs can assist students in accessing their career aspirations.

It is also clear in the research that internship opportunities benefitted all students in preparing them for their future careers and provided beneficial experience and skills more broadly. Finley and McNair noted that there were specific groups that seemed to show the greatest impact when participating in high-impact practices, such as internships. Latinx and African-American students showed greater increases in “self-reported gains, grade point averages, and retention.”9 Kinzie also found that, with increased participation, Latinx students were graduating in fewer semesters than those not participating, but that both “Latino and African-American students participate in internships less frequently than white students.”10 Though research shows internships may provide even greater benefits to students of color and low-income students, we lack research into the obstacles that prevent these students from participating.

– Student

In most of the research, the population of the student body studied was shown to be quite different than that of MSU Denver. Our demographics represent a seemingly growing population in the United States: urban, nontraditional, and greatly first generation. Kinzie shares the need for more diverse ideas on how to provide access to experiential learning, and one way to try to address that need may be “more responsive financial aid rewards…”11 We hope that MSU Denver’s “earn and learn” program will add to this body of research to look at whether institutional internship funding will increase participation for broader groups of students.

Studying the Potential Impact of “Earn and Learn”

The premise for our own study was that, if we could guarantee pay for internships in majors that traditionally do not have many options for paid internships, we would then be able to look at the students who took advantage of this opportunity and compare them to a previous cohort who did not have the option of a paid internship.

We selected three majors for the “earn and learn” program: political science, psychology, and biology. These are majors at MSU Denver in which internships are encouraged, but not required, and fields in which there are few paid opportunities. In October 2018, we began marketing to students in the three majors. The message was that any student in the selected majors who got an unpaid internship for spring 2019 would be paid by the university for their internship hours.

We had three research questions that we hoped to answer:

- Does offering pay for traditionally unpaid internships increase the number of students able and willing to complete internships?

- Does offering pay for traditionally unpaid internships change the demographics of students doing internships?

- What impact does internship pay have on the internship experience?

Our comparison group were students from the same three majors who did internships in spring 2018. By looking at the numbers and demographics of the unpaid students from spring 2018 compared to the paid group from 2019, we hoped to answer the first two questions. Surveys of the students and their supervisors would provide the answer to the third research question.

Findings: Socio-Economic Status Affected Participation

The results were dramatic: The spring 2018 comparison group (unpaid interns from the three target majors) consisted of 22 students. When given the opportunity for a paid internship, the number of interns in the three target majors for spring 2019 jumped to 50—an increase of 127 percent. This provides strong evidence that offering pay in fields that traditionally do not have paid internships has the potential to increase the number of interns.

In addition, the demographics of the groups were compared on the basis of Pell eligibility, first-generation status, race/ethnicity, and gender.

Interestingly, there were no significant differences in any of these areas except Pell eligibility: Twenty-seven percent of the 2018 students were Pell eligible and 56 percent of the 2019 students were Pell eligible. (This difference was statistically significant at the α = 0.05 level.)

It is interesting that, among those taking part in our study, socio-economic status was significant, while the other demographic factors were not. It raises the possibility that financial need is a bigger barrier to internship participation than other demographic factors. This is an area for further exploration with a larger pool.

Findings: The Impact of Pay

– Student

Students and their internship supervisors were asked to complete surveys about the experience. A total of 41 students and 25 employers took part. (Some employers had multiple interns.) From these surveys, we were able to learn a little more about the impact of pay.

1. Pay as a motivator for doing an internship: Despite the efforts at publicity for the program, most of the students did not know about “earn and learn” until after they visited the office. This raises the question: Why did we see such a dramatic increase in internship numbers if most of the students did not know about it before starting their internship search?

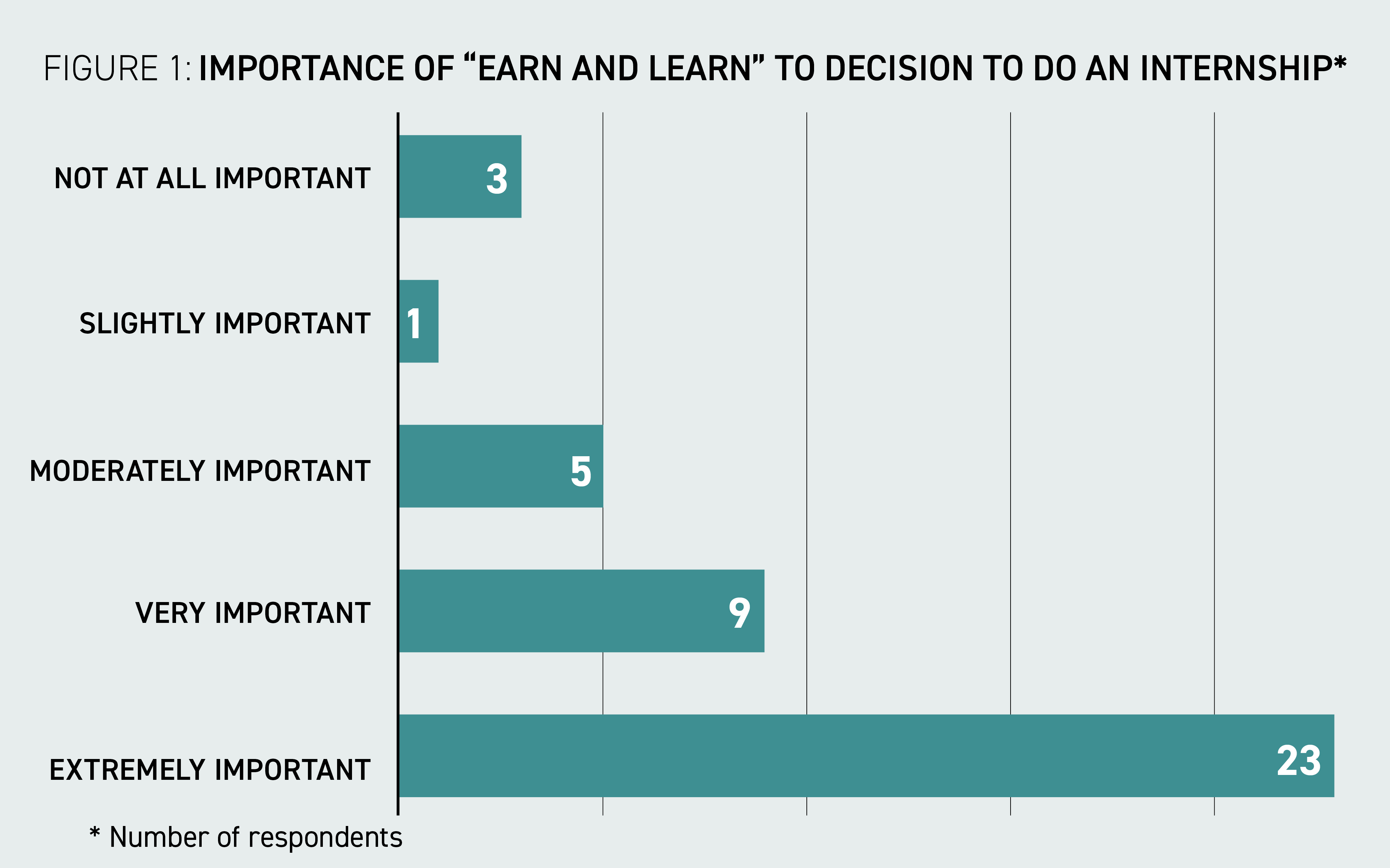

The answer may come from an exploration of the decision-making process. When asked about the importance of “earn and learn” to their decision to do an internship, students were clear: It was very or extremely important. So, while the publicity for the program may not have brought in a large influx of new students seeking an internship, the chance for pay “sealed the deal” for those students already thinking about doing an internship.

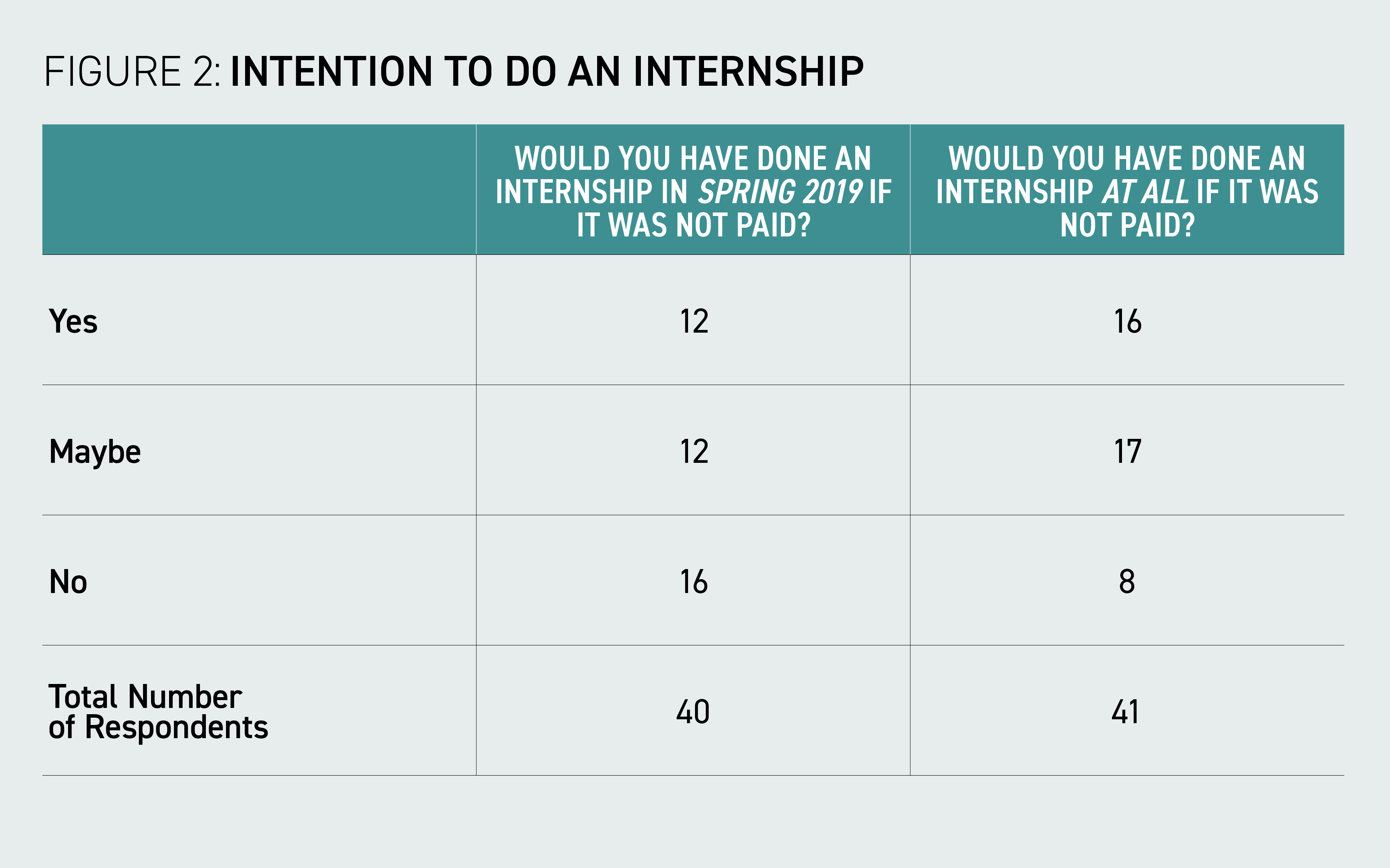

This was further explored through a question that asked students to assess how serious they were about doing an internship. Nearly 20 percent of the respondents were sure that they would never had done an internship without pay, and another 41 percent were not sure if they would have done one without pay. (See Figure 2.)

2. Impact of pay on the student: As a diverse, open-access institution, MSU Denver has a high number of students who are financially insecure.

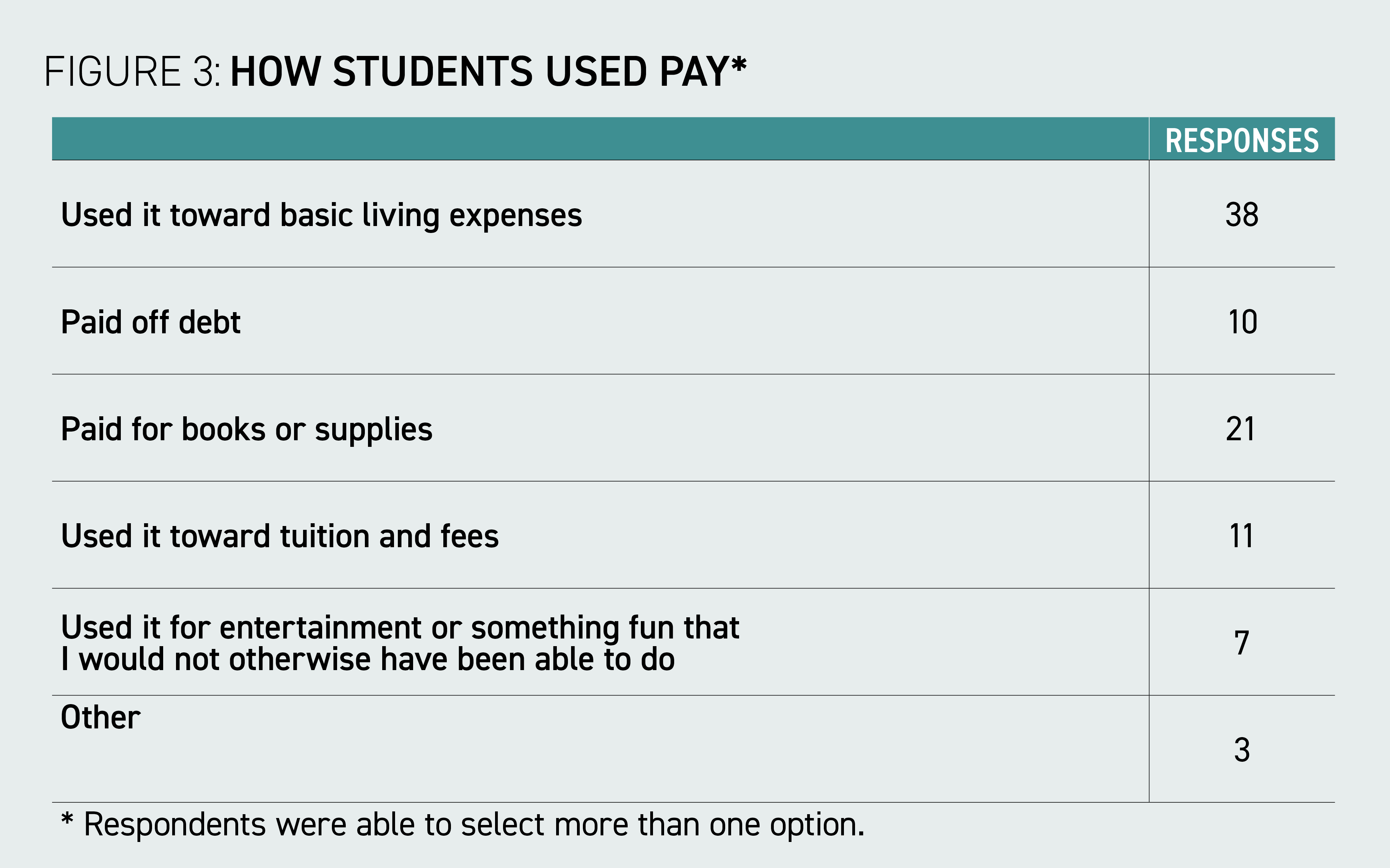

The “earn and learn” students were paid $12.50 per hour for a maximum of 150 hours and a total of less than $2,000 per student. This relatively small amount of money had a big impact. The money provided through the “earn and learn” program was overwhelmingly used to pay basic living expenses or pay for books and supplies. Students also indicated that they used the funds to pay for parking at their internship site or gas to get there. Only seven respondents indicated that any portion of the money was used for entertainment, illustrating how tight budgets are for many of our students. (See Figure 3.)

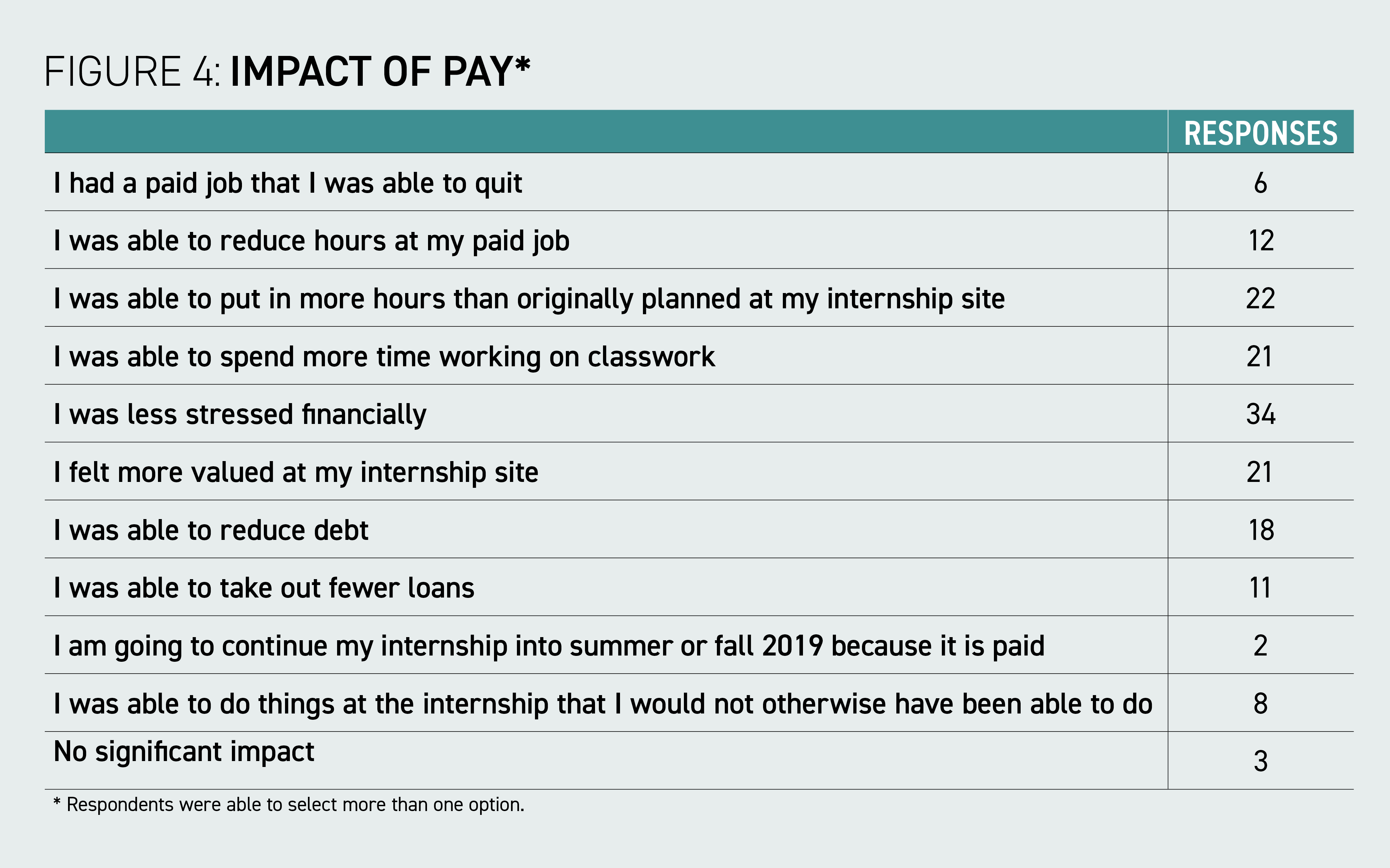

While the greatest impact of this money was a reduction in financial stress, there were other non-financial outcomes as well. For example, many students reported that they were able to spend more time on classwork. (See Figure 4.)

3. Pay creates a sense of value: Another non-financial outcome for students was a greater sense of feeling valued. According to some of the participating employers, their perception was that the pay made the students work harder and take the experience more seriously. So, while unpaid internships can provide good learning opportunities, the data we collected provide some evidence that pay can change the dynamic just enough to make the internship a more serious experience.

4. Impact of pay on future opportunities: It was noted above that the reason that biology, political science, and psychology majors were chosen for the pilot of this program was because these areas tend to have few paid opportunities for MSU Denver students. A large portion of the 33 organizations that took part in “earn and learn” identified themselves as nonprofits. Although these employers recognized the value of pay, when asked if there was potential for them to pay interns themselves in the future, the overwhelming answer was “no.” Only a couple indicated that they might be able to pay 25 percent of the intern’s wages as is required by some work-study programs.

It is easy to criticize unpaid internships as a function of employers trying to get “free labor” or take advantage of students, but the reality for MSU Denver students in some academic fields is that opportunities are often found in organizations that simply cannot pay. In written comments on the survey, employers expressed strong appreciation for the program as a means of providing pay to students.

Because employers recognized the value of the program, we harbored a secret hope that, if we continued the program, these employers might begin to give preference to MSU Denver students over other schools for internship slots in the future. This was not the case. Although a few indicated that “earn and learn” might give our students an edge—all other things being equal—half told us that the funding alone would not be enough to increase the number of MSU Denver students they would select for future internship openings.

Other Outcomes

In addition to the financing of internships, the “earn and learn” program gave us the opportunity to have more control over the internship experience. At MSU Denver, academic assignments and class requirements are set by the academic department. “Earn and learn” gave the internship program staff a chance to add some requirements of our own. We took advantage of this by adding a presentation requirement for all participating students. Interns were asked to create a poster or oral presentation about their internship experience to present at our Student Impact and Innovation Showcase, to which their faculty advisers and site supervisors were invited. Despite the additional requirement, students were excited about the chance to share their internship experiences. The added benefit was that they could add a conference presentation to their resume.

“Earn and learn” has also enhanced our relationship with our employers and community partners. They were appreciative of what the university is trying to do. Many saw themselves as beneficiaries of the program as much as the students; without financial issues as a barrier, they had a larger pool of candidates from which to choose.

Next Steps for the 2019-20 Academic Year

The answer to our research questions is yes, we were able to increase the number and socio-economic diversity of students doing internships by providing pay. This result did not go unnoticed by the administration and has attracted attention across campus. With some additional funding, we now have the chance to move beyond a pilot program and create a sustainable initiative.

For 2019-20, we are establishing a new process to reach students in more majors through “earn and learn” and are partnering with the university’s human resources department to streamline the application and selection processes. Students will be required to apply to the program through a multi-question application that will base qualification for the program on financial need and professional impact. We anticipate funding experiences for approximately 65 students in the spring.

We also ramped up the requirements for taking part in the program. Accepted students participate in an initial information session to set the stage for the semester and attend a “lunch and learn” session mid-semester to provide further professional development and cohort camaraderie in addition to presenting at the Student Impact & Innovation Showcase.

Although the funding for the program is not guaranteed long term, we are confident that this program is impactful enough that we will be able to find a variety of funding sources to keep it growing. For example, we have already had a department chair indicate interest in using some department funds for his students.

Over time, the plan is to build out a pool of qualified students and, eventually, approved employers to connect our students with for quality experiences. These additional standards will allow us to address some of our limitations and show potential funders—including departments and industry partners interested in supporting the university—that we are set and “ready to roll” as soon as consistent funding is provided.

In much of the discussion about unpaid internships, one position is that unpaid internships should just not be allowed. The reality is that, for students in some majors, there simply are not enough opportunities with organizations that can afford to pay interns. Eliminating unpaid internships will not help these students but will put them further behind their peers in fields that offer more plentiful paid internships. The “earn and learn” initiative was a solution that made it more feasible for financially insecure students to get the benefits of the internship experience. The initial results are an encouraging sign that we can open doors to more students to do internships regardless of the employer’s ability to pay.

In addition to the increase in numbers, we also found evidence that pay can change the nature of the experience by making it a more serious and valued experience for both the student and employer. Clearly, pay reduces student financial stress, and this could have a host of other positive ramifications.

In the short term, we think it unlikely that “earn and learn” will lead to jobs with the internship employer: Our experience has been that employers offering unpaid internships are often small start-ups or nonprofits with few jobs available. However, even in the short term, we are seeing other types of benefits accrue from the program, including enhanced relationships with faculty as there is greater buy-in from departments. We recognize that, with such a small study, it will be a challenge to determine if long-term career outcomes emerge for the “earn and learn” students. Still, we are excited about the future and look forward to identifying longer-term impacts of the program.

Endnotes

1 Kuh, G. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

2 Guarise, D. & Kostenblatt, J. (2018). The Impact of Unpaid Internships on Career Success of Liberal Arts Graduates. NACE Journal, September 2018.

3 Saltikoff, N., Albers, A., Rossi-Le, L. & Hall, E. (2018). Unpaid Internships and Early Career Outcomes. NACE Journal, May 2018.

4 Crain, A. (2016). Unpaid Internships of College Student Career Development and Employment Outcomes. NACE Journal December, 2016.

5 Townsley, E., Lierman, L., Watermill, J., & Rousseau, D. (2017) The Impact of Undergraduate Internships on Post-Graduate Outcomes for the Liberal Arts. NACE Center for Career Development and Talent Acquisition. September, 2017.

6 Lierman, L., Townsley, E., Watermill, J., & Rousseau, D. (2017). Internships: Career Outcomes for the Liberal Arts. NACE Journal, May 2017.

7 Gardner, P. (2010). The Debate Over Unpaid College Internships. Intern Bridge, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.ceri.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Intern-Bridge-Unpaid-College-Internship-Report-FINAL.pdf

8 Mayo, L. & Shethji, P. (2010). Reducing Internship Inequity. Diversity & Democracy, Fall 2010, Vol. 13, No. 3. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/reducing-internship-inequity.

9 Finley, A. & McNair, T. (2013) Assessing Underserved Students’ Engagement in High-Impact Practices. Association of American Colleges and Universities.Retrieved from https://leapconnections.aacu.org/system/files/assessinghipsmcnairfinley_0.pdf

10 Kinzie, J. (2012). High-Impact Practices: Promoting Participation for All Students, Diversity and Democracy Fall 2012, Vol. 15, No. 3. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/high-impact-practices-promoting-participation-all-students.

11 Ibid.