NACE Journal, May 2018

In the wake of the presidential election in 2016, higher education leaders are confronting a tumultuous landscape that features renewed emphasis on vocational outcomes, growing condemnations of colleges as liberal strongholds, and critical outcry about the worth of postsecondary education. While some administrators might downplay higher education’s opponents as an outspoken minority, there are others who see the “Trump Effect” as a very real phenomenon, with equally real implications for areas such as international student recruitment, campus security, and Title IX policy enforcement.1 Additionally, the political turmoil that has swept across the United States in the past several years has also forced college administrators to acknowledge that many stakeholders feel left out of the broader economic and educational opportunity structure in our country. In particular, higher education leaders are sitting up and taking notice of a forgotten segment of American society—the rural students, parents, and community members who feel increasingly marginalized by our higher education system.

The Importance of Rural Students

Why is it important to talk about rural students, and is it worthwhile to focus on this group of stakeholders in particular? Such an emphasis is important for a number of different reasons. Consider the following data points:

- 72 percent of the U.S. landmass is considered rural, and around 18 percent of K-12 public school students attend a school that is classified as rural.2 Rural students may have less access to high-speed internet, AP coursework, or extracurricular opportunities, and low-income rural students may face unique challenges related to transportation, childcare, food insecurity, housing, and healthcare.3 Many rural students may feel self-conscious about their academic abilities, and rural students are more likely to “undermatch” themselves when applying to colleges.4

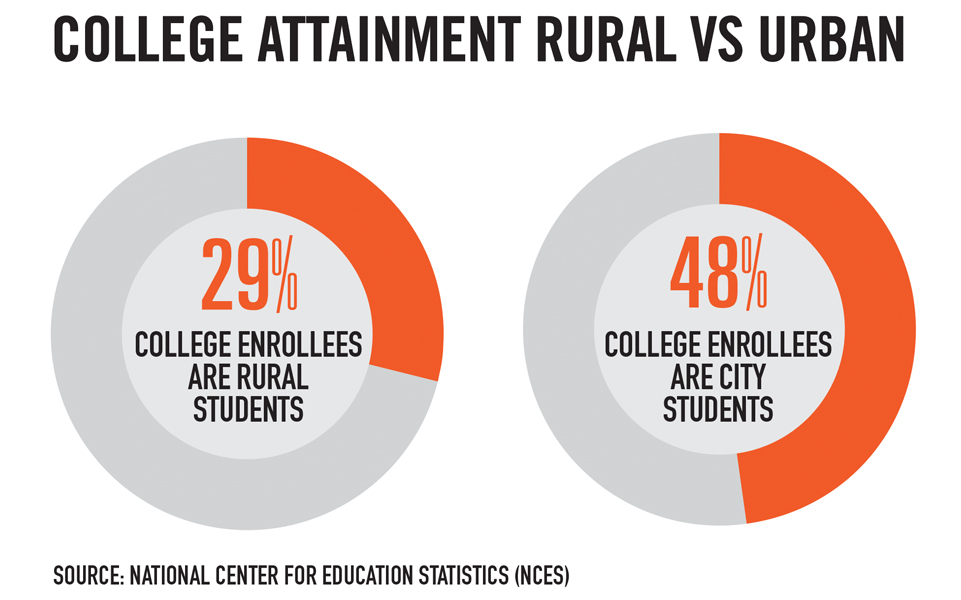

- The college attainment gap between rural and urban students is widening. National Student Clearinghouse data show that 59 percent of rural high school graduates enroll in college the following fall compared to 62 percent of urban high school graduates and 67 percent of suburban high school graduates. These margins are exacerbated by lower persistence and completion rates,5 with data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) showing that only 29 percent of college enrollees are rural students compared to 48 percent from cities.6

- Perhaps most challenging of all is the fact that rural students often come from communities where locally available jobs don’t require a college degree and many residents fail to see the value in higher education. A September 2017 poll by NBC News and The Wall Street Journal found that only 33 percent of rural dwellers considered a four-year college degree to be worthwhile, rating this demographic far lower than urban dwellers (52 percent), Republicans (43 percent), Trump voters (42 percent), or those with a high school diploma or less (43 percent).7

Given these statistics, it is not surprising that many postsecondary institutions, state policymakers, and intermediary organizations are making a renewed push to engage rural students.

Last year, the University of North Carolina system released a strategic plan that focused on bolstering rural student enrollment.8 The University of Georgia recently announced a new initiative to support rural student success.9 Clemson University and Texas A&M have also expanded their rural recruitment efforts, with Texas A&M Director of Admissions Scott McDonald arguing that “In terms of diversity, geography is just as important as racial and ethnic.”10 Liberal arts colleges such as Swarthmore College, Carleton College, and Warren Wilson College have launched strategic admissions initiatives aimed at rural communities as well,11 and organizations such as the College Board and the College Advising Corps are seeking ways to facilitate the application process for students in more remote areas.12 In short, there is widespread evidence of a recruitment and retention groundswell focused upon rural students. For campus career centers the question is: Are we prepared to support them when they arrive?

Supporting Rural Students

To be fair, most approaches to career counseling and coaching are not particularly place-bound. One of my favorite models, appreciate advising, offers a strengths-based approach that focuses primarily on what the student brings to the table—not his or her deficits. However, it is also important to acknowledge the limitations and pitfalls of how various advising approaches may apply to rural student populations. Coaching models with a strong future-orientation and a heavier emphasis on the client’s role in the development process may be uncomfortable to navigate for students who have had little previous interaction with professional advisers. And, any approach designed to help elicit a student’s career potential could be limited for rural students who come from areas that, by definition, offer less exposure to various economic fields.

While many career development models seek to factor in environmental influences, in practice this variable can sometimes get lost in the shuffle. Take for example Donald Super’s life-span, life space” approach to career development. In this model, Super outlines the various roles and life stages that may occur within a person’s life-span, with roles sometimes overlapping or manifesting in different “theaters” (such as work, home, community settings, and so forth). Super argues that both situational determinants—“geographic, historical, social, and economic conditions in which the individual functions from infancy through adulthood and old age”—and personal determinants—interests, values, needs, aptitudes and self-awareness—work in conjunction to shape an individual’s career development path via a series of key decision points.13 Although this model seems intuitive even today, I would argue that a much larger emphasis in college career advising is often placed on personal determinants and not situational factors as outlined above. For many students, and particularly for rural students, these situational considerations can play an important role in career development and decision-making.

To elaborate further on this idea, we may begin by considering the notion of habitus, which was posed by Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu characterizes habitus as a set of “permanent dispositions” that guides our behavior.14 One’s habitus is shaped largely by one’s habitat—that is to say, an internalized worldview drawn from the socio-cultural surroundings with which one is surrounded from an early age. Even when one transitions to new surroundings (as Bourdieu would say, from one field to another), his or her habitus continues to influence daily practices. In essence, one’s habitus guides the individual’s perceptions of the “rules of the game” and overall interpretations of the world around him or her. These dispositions can serve to place students in a state of either advantage or disadvantage as they transition from their home communities to college and ultimately embark on their career path.15

Focusing specifically on rural students, Dees expands this theme with an exploration of the college acculturation process for students from rural Appalachia.16 She finds that rural students encountering new ideas in the college classroom are often faced with either adopting the ideas of the dominant culture, denying these ideas, or negotiating another form of adjustment altogether (such as becoming bicultural or rejecting both the dominant and subordinate cultures). The participants in her qualitative study articulated their unique rural/Appalachian cultural values in the following ways:

- Realization of the importance of family

- Strong sense of community

- Belief that “common sense” is more important than intellectual ability

- Mistrust of those outside the community

- Adherence to gender-role stereotypes

- Strong work ethic

- Strong religious beliefs

In her analysis, Dees discusses the ways in which the adjustment process may be problematic for rural enrollees, saying:

“Like immigrant sojourners into another culture, rural/Appalachian college students encounter brief visits into a dominant cultural system that may be very different from their own. The university classroom, through power relationships that are constructed through cultural norms such as grading, classroom expectations, and professor–student relationships, becomes a cultural system with hidden rules that may be difficult for students to negotiate. Additionally, when the dominant culture, represented in this study as the college classroom, presents ideas that conflict with the students’ home culture, an added sense of stress is created in the students’ lives.”17

Students reported struggling to balance family connections, being suddenly recast as an outsider in their home communities, or navigating work obligations that interfered with their educational goals.

Ali and Saunders, in a separate study on rural Appalachian youth, highlight the presence of “stereotypes and other contextual factors,” such as pressure to remain near home, which can have a dramatic impact on both career aspirations and achievement.18 In addition, “rural Appalachian adolescents contend with a variety of within group cultural messages about the value and need for education.”19 The authors also point out that educational systems are often inherently biased toward certain (middle and upper) classes of society, stating that rural youth may temper their career expectations because they do not feel socially accepted in the educational landscape they must traverse to reach such goals.20 Related studies have identified other negative influences, citing that more than half of Appalachian students surveyed had received discouraging messages from others about their pursuit of higher education.21 Students reported struggling to balance family connections, being suddenly recast as an outsider in their home communities, or navigating work obligations that interfered with their educational goals. While economic circumstances at one time dictated that higher education was not necessarily a prerequisite for vocational success, challenges such as these often leave rural youth unprepared to enter today’s rapidly changing work force.

Michael Corbett, a sociologist of education who has studied rural students extensively, elaborates on this perspective and also points out that career development in the modern world is much more complex than Super would have us believe. Corbett draws upon interviews with students and parents to assess the “spatial and temporal tensions” of families and youth who are seeking to establish educational and life trajectories in rapidly changing rural communities.22 He points out that chronic uncertainty and ambivalence have become trademark characteristics of modernity—characteristics that sometimes contrast sharply with traditional rural values and ways of life.23

To illustrate this argument, Corbett outlines five parental “child-rearing frames,” which emerged from his interviews with rural families. His point is to articulate the ways in which these place-bound strategies serve to cultivate identities and educational trajectories for rural students. They are as follows:

- Competitive Frame: School is viewed as preparation for a fundamentally competitive world of scarce resources. Parents emphasize grades, test scores, and other tangible outcomes.

- Pragmatic Frame: School is constructed as work in its own right, as well as direct preparation for a future vocation.

- Security Frame: This frame emphasizes the relative safety of community life versus the perceived insecurity of spaces outside the community.

- Entrepreneurial Frame: This frame acknowledges the economic and social realities of resource decline and emphasizes the need for all players to become more inventive and creative.

- Exploratory Frame: Associated with the professional middle class, this frame emphasizes the role of schooling in personal growth and development—in particular, there is an acknowledgement that it may take time for individuals to progress through a period of emergent adulthood.

Emphasizing this latter point, Corbett posits that exploratory time (i.e., emergent adulthood) is not a universally accepted norm, but a feature of privileged society; for many individuals, he argues, there is a need to step more quickly from adolescence into productive adulthood:

“The difficulty with the emerging adulthood literature… [is the assumption] that the widening space between childhood and adulthood is a universal feature of late modernity culminating in the present moment with a new protracted identity exploration space which follows secondary school graduation. However, all youth do not experience the temporal space between the ages of 17 and 24 as an open-ended identity search. In fact, most youth from what might be called working class or low SES families are pressured to ‘get serious’ and to do it quickly.”24

In short, many rural students could be experiencing unique pressures to a) identify a field of study that might be considered economically pragmatic (and do so as quickly as possible), b) maintain connections to their home communities, and c) establish themselves as competent and competitive students, even though they may be entering college with limited social and cultural capital (or dramatically different forms of capital) when compared to their peers.

Preparing to Serve Rural Students

Given these realities, how can we best prepare ourselves to serve the rural students on our campuses?

In truth, it is hard to fully understand the needs of rural students because there is so much heterogeneity among rural communities, which vary dramatically by region; economic prosperity; social diversity; and political, cultural or religious views. Think, for instance, of the unique economic, geographic, and socio-cultural distinctions between rural Appalachia, rural Texas, and rural Mississippi. Even within these settings, we may encounter significant amounts of variation—a challenging dynamic that has always plagued the field of rural sociology.

One starting point for this difficult task is simply considering ways to acknowledge and address the unique career development needs of rural students on our campuses. For example, Ali and Saunders call for improved support structures to help students integrate academic life with long-term career planning.25 In college, this might mean closer ties between academic and career advising early on. Particularly for low-income students with strong ties to home, reflection and education about rurality as a cultural identity may help students navigate some of the challenges they will encounter. Career assessments could be strategically designed or selected to capture context-specific measures—the situational determinants of Super’s framework. Furthermore, I would argue that this strategy applies not only within assessment practices, but also in more contextualized approaches to career advising and exploration.

As career centers play an increasing role in tracking student outcomes, we have a unique opportunity to understand how students move through our institutions and launch their career trajectories.

For example, career development staff might consider increased usage of exploratory questions that focus on social background (“Tell me about your hometown,” or “Tell me about your family”), self-efficacy (“What career-related goals have you established already?,” “Who are your biggest role models?,” or “What are some ideas that you would like help to uncover further?”), and life/career trajectories (“Do you want to go back to your hometown when you graduate? Why or why not?”). Career advising questions could also be framed to uncover rural norms and values, including pragmatic outlooks on career selection, gendered career stereotypes, or other misconceptions and unique dispositions. Staff who encounter rural students regularly may benefit from refreshing themselves on career development paradigms that are amenable to this population. Examples might include social cognition career theory (SCCT)26 or circumscription and compromise theory,27 both of which emphasize the significance of environmental and social influences.

As with other dimensions of modern college life, it is important to consider the central role that parents and families can play in student decision-making. How do we allow opportunities for students and parents to partner in leveraging career development resources? How can we train our staff to help students navigate career decisions that may ultimately result in permanent departure from their home communities—a process that Michael Corbett calls “learning to leave”?28 In some cases, this task may involve providing students with the necessary tools to communicate their plans to family and friends and/or cope with any negative consequences of their decision, as well as finding ways for both students and staff to educate rural parents on the potential value of an extended career exploration period.

Lastly, we should ask ourselves how we can contribute to learning more about this issue. As career centers play an increasing role in tracking student outcomes, we have a unique opportunity to understand how students move through our institutions and launch their career trajectories. In particular, we might consider the many ways in which career centers—particularly at larger institutions—play a role in funneling students toward urban career opportunities and away from their rural communities. One contributing factor is the limited array of career paths that are available in rural communities. However, it is also possible that career centers help normalize the pursuit of urbanized career paths by highlighting corporate partnerships, emphasizing those professional skills and norms that are predominant in corporate America, or through an overrepresentation of urban-corporate speakers, role models, and experiential learning opportunities within the career development curriculum. Much more research is needed on this question to further understand whether more equitable practices might be developed.

In summary, there is currently no coherent career development framework that focuses explicitly on rural college students. However, there are plentiful opportunities for career advisers to reflect upon and adapt existing practices with this population in mind. For many seasoned career development staff members, the challenges outlined above offer few surprises. Many rural students have traversed our campuses before with great success, and many institutions today successfully serve student populations that are significantly (if not predominantly) rural. With higher education leaders around the country demonstrating renewed interest in rural students and communities, the time has come to revisit the unique needs of this demographic as we seek to ensure that everyone feels welcomed and supported within our institutions.

End Notes

1 Anderson, N. (2017). The Trump effect in college admissions: Rural outreach increases, international recruitment gets harder. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2017/09/13/the-trump-effect-in-college-admissions-rural-outreach-increases-international-recruitment-gets-harder/?utm_term=.3e0e572bd0fe.

2 Pappano, L. (2017). Colleges discover the rural student. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/education/edlife/colleges-discover-rural-student.html.

4 Mader, J. (2015). Study: Rural Indiana students more likely to ‘undermatch’ in college enrollment. Education Week. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/rural_education/2015/06/study_rural_indiana_students_more_likely_to_undermatch_in_college_enrollment.html.

5 The University of Georgia (2018). Task force on student learning and success. Appendix 3, p. 37. Retrieved from: https://president.uga.edu/_resources/documents/final_task_force_report.pdf

6 Marcus, J. & Krupnick, M. (2017). The rural higher education crisis. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/09/the-rural-higher-education-crisis/541188/.

7 Cann, C. (2017). Americans split on whether 4-year college degree is worth the cost. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/first-read/americans-split-whether-4-year-college-degree-worth-cost-n799336.

8 Spellings, M. (2017). UNC’s plan seeks to close the gap between the ‘two North Carolinas’. The News & Observer. Retrieved from http://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/op-ed/article190172169.html.

9 Stirgus, E. (2018). UGA president announces plans to help rural and low-income students. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from https://www.myajc.com/news/local-education/uga-president-announces-plans-help-rural-and-low-income-students/ypTcilTRMyTKbRTOh2iIEO/.

10 Pappano

11 EAB (2017). Why colleges are working to win over skeptical rural students. Retrieved from https://www.eab.com/daily-briefing/2017/12/07/how-and-why-colleges-are-recruiting-rural-students.

12 Pappano

13 Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of vocational behavior, 16(3), p. 295.

14 Bourdieu, P. (1993). Sociology in question (Vol. 18). Sage. p. 86.

15 Grenfell, M. J. (Ed.) (2014). Pierre Bourdieu: key concepts. Routledge.

16 Dees, D. M. (2006). “How Do I Deal With These New Ideas?”: The Psychological Acculturation of Rural Students. Journal of Research in Rural Education.

17 Dees, p. 2.

18 Ali, R. S., & Saunders, J. L. (2009). The career aspirations of rural Appalachian high school students. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(2), 172-188.

19 Ali & Saunders, p. 172.

20 deMarrais, K. B. (1998). Urban Appalachian children: An "invisible minority" in city schools. In S. Books (Ed.) Sociocultural, political, and historical studies in education. Invisible children in the society and its schools (pp. 89-110). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

21 Wallace, L. A., & Diekroger, D. K. (2000). "The ABCs in Appalachia": A descriptive view of perceptions of higher education in Appalachian culture. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Women of Appalachia: Their Heritage and Accomplishments (2nd). Zanesville, OH.

22 Corbett, M. (2009). No time to fool around with the wrong education: Socialisation frames, timing and high-stakes educational decision making in changing rural places. Rural Society, 19(2), 163-177.

23 Corbett (2009)

24 Corbett (2009), p. 172.

25 Ali & Saunders

26 Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (1996). Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. The Career Development Quarterly, 44(4), 310-321.

27 Gottfredson, L. S. (2002). Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation. Career choice and development, 4, 85-148.

28 Corbett, M. (2007). Learning to leave: The irony of schooling in a coastal community. Cornell University: Fernwood Publishing.