NACE Journal, February 2018

Career centers at institutions large and small face a problem in common: how to scale our services to reach as many students as possible with quality, customized programs.

The University of Nevada, Reno has found success with a surprising new model: We ended career counseling and even appointments. Instead, the doors stay open for drop-in visits until 8 p.m. every weeknight. All career advising is done by undergraduate students in an open-plan studio. The professional team gets to focus on everything but meeting individually with students.

A Chance to Reinvent

I was hired by the University of Nevada, Reno in 2013, part of a two-person team with a charge to offer career services to 20,000 students. Deep cuts to the budget during the economic recession had led to a closure of the university’s central career services office a few years earlier. Now, we had an opportunity rare in higher education: to invent a new career center, working from the ground up.

One thing was clear: The traditional model of career services would not get us very far. Even if we both emptied our schedules of anything but appointments, my colleague and I would manage to help only a small fraction of students. Further, this would leave no time to develop the resources, programs, and connections that give advising sessions their value. An idea for a new kind of career center began taking shape—one without any appointments. Without appointments, our staff would have more time to invest in innovation and development: programming, partnerships, events, external relations, and training. There was just one problem: In this new model, who would help students with their individual career questions?

We were inspired by programs that empower students to work directly with their peers.

The traditional model for university career services looks something like this: Professional staff handle most “frontline” services, such as counseling appointments and drop-in advising, while also working hard behind the scenes to plan and implement programs. Student employees often help fill in the gaps. At many schools, student workers pitch in to do a little bit of everything. They work the reception desk, assist with career fairs, promote events, and/or curate the social media accounts. A growing number of schools train students as “career peers,” and give them the opportunity to do some hands-on work with students, such as resume critiques during limited drop-in hours.

We were inspired by programs that empower students to work directly with their peers. We wanted to see how far we could take the concept of peer education in career services. So, we flipped the traditional model. We placed student “career mentors” in a role traditionally reserved for professional counselors. Student employees would become the frontline providers, with one important twist: With no appointments, everything would happen on a drop-in basis. Our office would be a career studio, an open-plan space where a team of peer mentors is always ready to help the student with his or her career. This would be a space where students could drop by day and night to get help with a resume, prepare for an interview, search the job board, or talk through a tough career decision—all with the help of their peers.

That first year, we posted a job description of a “career mentor” and worked through two rounds of interviews before making job offers to eight undergraduate students. The positions were funded using money that had been earmarked for another part-time professional hire—money we thought we could put to better use by funding peer educators. We spent 40 hours training the new career mentor team the week before school started. Then we opened the Career Studio doors and waited for our first clients to walk in.

How It Works

Picture a typical afternoon in the Career Studio. Several students work at computers, typing edits to Word documents and clicking through job posts. Backpacks and jackets are strewn everywhere. Outfitted in navy blue polo shirts, with the Nevada “N” stitched onto a sleeve, career mentors buzz around the room and touch base with their clients. A mock interview is underway in the comfy chairs at one end of the room, the mentor jotting notes as she listens. Tables are pushed together to make space for an impromptu group of three freshmen who walked in separately, all with questions about writing cover letters. One young man walks slowly around the room’s perimeter, selecting resume samples and tip sheets to use at home. As another student readies to leave for class, a career mentor snags her for a quick exit interview on a tablet.

Open for drop-ins 44 hours a week, our Career Studio is dynamic, welcoming space. Between two and four mentors work the floor at a time, adapting to the changing needs of the room. Some students (we refer to them as “clients”) are looking for a deep dive one-on-one with a mentor, while others prefer to work largely on their own. The average length of a drop-in visit is a little over an hour, but there really is no such thing as an average visit. Students know they can just pop in for a few minutes to have a quick conversation (“Can someone look over this thank-you note before I send it to the interviewer?”), or just as easily set up camp at a computer while they add finishing touches to a dozen job applications. Each mentor knows what every client is working on, and they seamlessly work the room to make sure everyone is getting what they need.

Professional staff walk through the Studio a few dozen times in a day, sometimes sitting down with a client when we see that things are busy, jotting observation notes to discuss later with a mentor, or chiming in to add our two cents to a group conversation. Occasionally, career mentors pull one of us onto the Studio floor to help a client with an especially challenging request. We always open such conversations to include the career mentors as well, turning these conversations into learning labs for anyone in the Studio. This is part of our larger strategy to elevate the role of student employees as the true leaders of the Career Studio. Professional staff are careful never to give an impression that professionals are the “real deal,” while career mentors are merely students. The effort seems to pay off, as students rarely question our peer-to-peer setup.

Hire for Heart, Train for Technique

Our hiring process for career mentors is very selective and includes an online application followed by two rounds of interviews. There are no requirements for class standing or major—each year, we end up hiring a team that ranges from sophomore to senior, spanning every academic college. Although professionalism is a critical part of the job, we do not necessarily hire the students with the best resumes, nor the ones with the most work experience. Instead, we look for students who can demonstrate an appreciation for diversity, aptitude and experience teaching, and the ability to connect naturally and warmly with others. Group interviews help us discern which applicants are comfortable engaging openly with their peers. Technical skills—how to write an effective resume, craft a strong answer to a tricky interview question, and so forth—can be taught, and mentoring techniques can be practiced. But the heart of a mentor, a true dedication to helping others find their best, has no substitute.

Once we hire our career mentors, the real work begins—teaching them how to do everything. With the time we’re not spending in appointments, our professional team invests in continuous improvement of our mentor training program. We consider this the Career Studio’s most important project. The robust training curriculum incorporates extensive summer training and onboarding; year-round weekly meetings; and an ongoing cycle of observations, evaluation, and guided reflective practice. All training is mandatory and paid; for us, the training is as important to the job as is the work with drop-in clients.

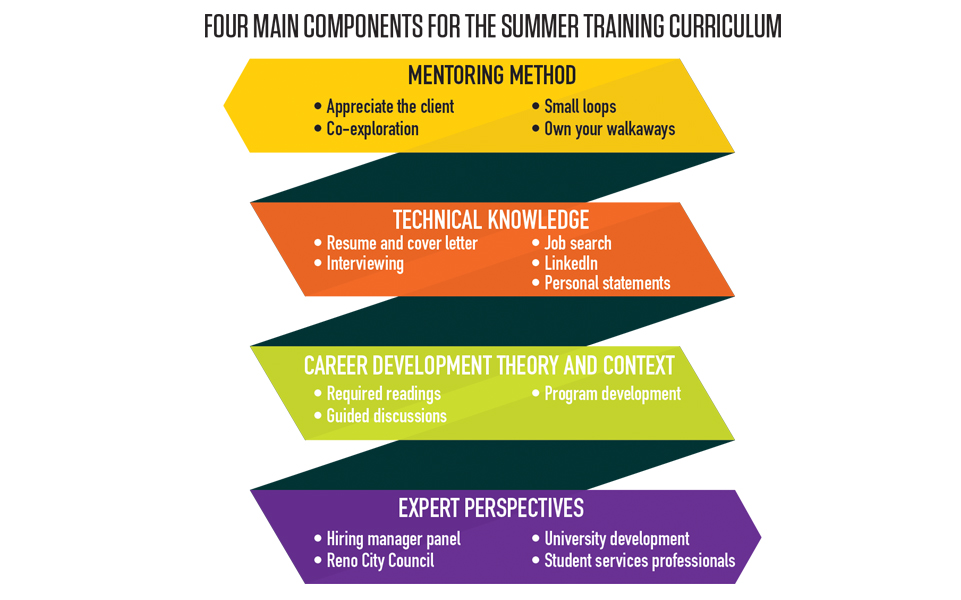

Every summer the new hires participate in 45 hours of (paid) training and complete a set of summer reading assignments. This initial training addresses the NACE Professional Competencies for College and University Career Services Practitioners, aligned to the basic level of proficiency. During the school year, mentors participate in weekly training meetings to hone technical skills and problem-solve tricky client interactions.

The ongoing, year-round nature of training encourages us to tinker constantly with elements of what we teach the mentors, how we teach it, and how they can serve their peers with greatest impact. Teaching technical skills such as resume writing and interviewing is easy to do, compared with the challenge of teaching how to be a good mentor. Over time, the professional team has developed a framework to guide the career mentors in the art of mentoring, a set of core principles that we call the “studio method.” Career mentors are introduced to the studio method during summer training. From then on, everything that happens in the Studio comes back to our four principles of mentoring: appreciation, co-exploration, small loops, and walkaways. (See Calhoon’s article, “The Studio Method.”)

Is It Working?

Our staff remains very small—just three and one-half full-time professionals and one administrative staff member. The typical career center staffing for a university of more than 20,000 students is more than three times this size. Meanwhile, the career mentor team has steadily grown, increasing from eight students in year one to 18 in year five. Today, peer career mentors handle more than 3,000 drop-in visits in a year.

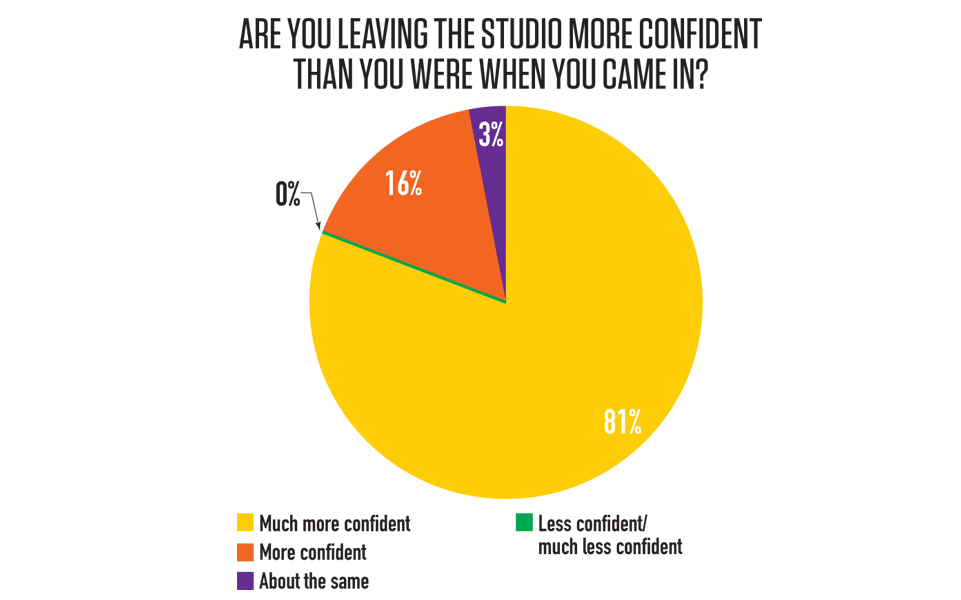

Frankly, when we debuted the Career Studio back in 2013, we expected a lot of pushback from students. Those fears turned out to be largely unfounded. Students not only do not seem to mind receiving career advice from their peers, but many actually prefer it. So, according to student feedback—yes, it is working. Since we introduced the exit survey in 2016, responses have been consistently, overwhelmingly positive: 97 percent of students in 2016-17 said that they were walking out feeling more confident, and 96 percent said that they knew their next steps as they left.

Another way we measure the Studio’s success is by taking stock of everything else our small team has accomplished while not holding appointments. In 2016-17, between drop-ins, career fairs, programs, and workshops, the Nevada Career Studio registered 10,000 touchpoints with students. Our career education team logged more than 70 hours in classrooms and another 50 hours teaching workshops outside the classroom. The employer relations team runs an award-winning Internship Grant Program, funding more than 60 paid internships at area nonprofits and startups. Last year’s calendar included five major hiring events and more than 60 other employer events. Revenue from career fairs, nonexistent our first year, now funds all wages for our growing student team. The studio model makes these achievements possible: We are not meeting with students one-on-one, so we have the time to accomplish programming on the scale of a much larger career office.

Five years after we opened, there is evidence that the Nevada Career Studio is securing a reputation as a vital, outcomes-focused resource for students and the community. We are fortunate in reporting up to a vice president who celebrates innovation and believes in the potential of peer-led learning. Thanks to her support, we had a tremendous opportunity to relocate into the new Pennington Student Achievement Center, along with other highly sought student resources, when the building opened in the heart of campus in 2016. Last spring, the Career Studio began traveling with the university’s recruitment team to meet with high school seniors and their families at admitted student receptions throughout Nevada and California. As a larger spotlight is applied to the question of career outcomes, and return on investment for higher education, our Career Studio has been poised to handle that spotlight. Our office has also taken on the project of reporting first-destination outcomes for the whole university, which puts us in conversations with stakeholders from academic deans to the president’s council to the state Board of Regents.

Benefits of a Career Studio

The benefits to students in a studio model are manifold. Peer-led, drop-in college career advising not only reaches more students, but also cultivates a collective attitude about career readiness that will serve students long after they graduate.

1. Reach more students with fewer professional staff: Extending career services’ reach on a campus requires easing the demand for one-to-one services. The studio model accomplishes this in two distinct ways. First, shifting more responsibility to student mentors opens more time for professional staff to do what we do best—develop and implement creative, smart programs that prepare students for the professional world. Time that would have been spent in one-to-one meetings gets reinvested in programs that serve many students at once. Second, drop-in visits can be much more efficient than individual appointments. Drop-ins easily accommodate more than one student at a time, especially in a space set up to invite independent work as well as guided coaching. With no expected time frame for a visit, students tend to stay for exactly as long as they need, and come back when it’s time for the next step. Another boon for efficiency: Without the option to make an appointment, students can’t forget to show up for one.

2. Invest in peer-led teaching and learning: Peer education helps students on both sides of the mentoring relationship learn skills of collaboration and problem solving. College students can be incredible resources for one another when it comes to making career plans and decisions. This is especially true for formative professional experiences, such as internships and part-time jobs. Imagine a first-year student with no work experience, hoping to land his first job on campus. At a traditional career center, his only option might be sitting down for an hour-long talk with a professional counselor, then applying for jobs at home. At the Career Studio, he gets the inside scoop on campus hiring from a college junior. He hangs out all week in the Studio to work on applications, with mentors nearby to answer questions as they come up. A few months later, he heads back to the Studio for advice on summer internships, knowing that he’ll find easy rapport with the career mentors and immediate, hands-on help.

We know that teamwork, collaboration, and communication are critical skills for the modern workplace. I would argue that these same skills are essential for personal career advancement. There exists no professional equivalent of the college career counselor, no sage adviser whose role is to help you further your career (for free!). Instead, you learn to have strategic conversations with the people you work with—you network for contacts, negotiate promotions, and seek career advice and feedback from co-workers you admire. Such conversations resemble the peer-to-peer interactions that take place in a college career studio. Ideally, your college career center is the place where you first learn how to talk with peers about what you want from your career, and ask for help taking concrete steps toward it. If so, it will serve you well throughout your whole career.

3. Encourage ownership of career planning: Our model shifts the role of the career center from “a place where you talk about your career” to “a place where you work on your career.” When a student comes to the Career Studio, we will put tools in his hand, show him new resources, plug him into opportunities, and teach him how to put his best foot forward. But we won’t tell the client what to do, and we won’t do it for him.

Anyone who works in our field can tell you why this transfer of ownership back to the student is so important. Career decisions do not end when the student lands that first job out of college! Students graduating from college today can expect to change jobs close to a dozen times. And those job changes reflect just the major decisions; in between will come countless smaller career decisions. It is critical that our work in career services prepares college students to navigate a lifetime of career choices, big and small, with confidence.

We do students no favors if we give them the impression that an hour-long meeting with an adviser will answer all their questions, setting them on the “right” path from then on. Few career counselors intend that message, but nonetheless students are primed to receive it. In the Studio setting, where coaching is peer-facilitated rather than expert-led, it is clear to students that they will get out of the Studio what they put into it.

4. Make career education a casual, everyday part of college life: The Career Studio works so well because it is designed to meet students’ needs on their own terms. Drop-in conversations with other students are far more casual and accessible than appointments in offices with professional counselors. Students come in exactly when they need help—because an application deadline looms or a phone interview starts in just a few hours. Dropping by the Career Studio is easy for students to work into an ordinary day. As a result, we have the opportunity to make career education an integrated part of ordinary college life.

Can the Career Studio Model Work for You?

I urge my colleagues in career services to consider these benefits for your own students. Can the career studio model work at your school? If not as a standalone operation, is there a way to pilot a peer-led, drop-in career studio alongside the work you do presently? My school flipped the whole career center because we could: We started as two people in an empty office, with nothing to lose if we tried it and failed. You likely find yourself at a different starting line, with talented staff and programs and systems that are well established. But perhaps you have a team of students working or volunteering for you, who would rise to the occasion if you trained them as career mentors. Maybe there is an awkwardly empty lobby somewhere that can be transformed into a multi-function studio for drop-ins. Perhaps, too, there is some aspect of your career center that you wouldn’t mind dismantling, flipping on its head to see what shakes down. Try it!

There is untapped potential in all our career centers. Potential for more creative programs, once our staff unlock space in their minds (and calendars) to dream them up. Potential for students to become compassionate, knowledgeable career coaches to their peers. Potential to rework how we provide career education to better equip today’s students and tomorrow’s world. I firmly hope that our experience in the Nevada Career Studio inspires other schools to experiment with how to tap into all of this potential in our collective quest to bring our work to scale.