Clarion University was part of a historic integration within the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (PASSHE). Since 2020, Clarion, California, and Edinboro Universities of Pennsylvania have worked to plan and execute the integration of their three unique, standalone universities to one shared model. As of July 1, 2022, we became Pennsylvania Western University (PennWest).

You can only begin to imagine the massive challenges we faced merging three cultures; three sets of curricula; and hundreds of software programs, systems, processes, procedures, and more. However, with each challenge came a significant opportunity to write history and, for us, reimagine our career centers.

As the inaugural executive director of the Center for Career and Professional Development at PennWest, I oversee a team of eight practitioners to support three geographically separated career centers and the career readiness of nearly 14,000 students, including our global online students.

California, Clarion, and Edinboro legacy career centers served their institutions well and used best practices to elevate their offices to the best of their abilities, given staffing and financial challenges. Now, we look to those best practices to create anew and continue the work of delicately weaving ourselves into the strategic goals and mission of PennWest.

Since that work is ongoing, and a story for another day, let me take you back nearly five years and share strategies in how the Clarion University career center was able to shift the narrative for career development and elevate its status within its campus culture.

As you’ll learn, these strategies are holistic and can be used regardless of organizational alignment, structure, or staffing size. I’ve shared these strategies with many colleagues over the years and learned that the main restriction is resistance to change.

The Beginning of the End

Clarion University was an institution of nearly 5,000 students, with roughly 40% being first generation and Pell eligible. The career center was an optional service to students and relied extensively on faculty partnerships to increase student engagement. At the time, our office was organizationally aligned with academic affairs and used a liaison model to support students. To become respected experts in those areas, each career coach was aligned to majors with at least one academic college.

Like many career centers, we struggled for years to increase the awareness of career readiness and convince others of how critical our work was to support the university mission. However, in late 2020, that changed after an internal restructuring due to a retirement.

After I was promoted to interim director of the career center, the provost charged me with “getting the career center to and through integration.” I remember jokingly asking if there was a roadmap for that. Of course, the answer was no, although it elicited a few chuckles.

My decade of military, business, and higher education experience told me to go back to the basics and keep it simple. So, after many individual and team conversations, the career center staff collectively decided it was important to hold strategic planning sessions to reflect on our progress, pinpoint strengths and opportunities, and identify the best modes of action to prepare for integration.

A Supportive Office Environment

Staff identified the following as important qualities of leaders to provide a supportive environment:- Visionary; driven by strategic planning, data, and understanding of local, regional, and system goals/objectives

- Collaborative approach in goal-setting, decision-making, and execution

- Support for professional development/training

- Transparent communication and feedback

- Clear expectations without micromanaging

- Flexible/adaptable

- Fair and equitable

- Reflective listening and support through advocacy

- Empathetic and approachable

Assessing Our “Why” Through Strategic Planning

Our reflection began by holding biweekly meetings over four months to assess three areas: 1) identifying what makes for a supportive office environment, 2) determining individual staff goals within the next two to three years, and 3) rethinking the long-term vision of career development.

This exercise was completed in three parts. Parts one and two were self-reflective. The staff were provided a document that asked them to outline how they want to be supported by a manager and what makes a supportive office environment. Each question allowed me to understand how I could support the individual characteristics of each staff member and, as a group, how we all wanted to be treated. Follow-up 1:1 meetings to discuss these areas took place, and the synthesis of “what made a supportive office environment” was shared with the entire group. (See “A Supportive Office Environment.”)

Staff were also asked to draft two or three personal and professional goals over the next two years, which was the timing for the integration. This exercise was used to understand what each member of the team desired and if they aspired beyond the career center, and, if so, how I could help them achieve their goals. I regularly reviewed these two exercises to ensure I was supporting the staff to the best of my ability.

Why start with “why’?

Although we are good at explaining what and how we do what we do, we often can’t fully articulate why we do it.For example, if you were to ask your team what you do in your career center, they would be able list your array of programs and services.

If you were to ask them how you provide those programs and services, the would be able to list the modalities and methods used.

But, if you ask them why you provide those programs and services, you are likely to get responses akin to “because we always have.”

Your “why” should never be a status quo statement. If you start with the “why”—which should be rooted in your mission—it immediately challenges the status quo and leads to a stronger “what you do” and “how you do it.”

Part three of our office strategic planning explored the long-term vision of the career center and lasted about three months. The team implemented Simon Sinek’s “start with why” theoretical framework, which challenges organizations to reflect on their “why” and let it drive “how” and “what” they do.

In applying this concept to our planning, I led the team through a variety of exercises that challenged us to think about 1) why we do what we do, 2) how we do it, and 3) what we should do/change for the future.

This began by evaluating why we do what we do through a review of our office mission and the mission and vision of the university to see if we were fulfilling our publicized promise to stakeholders. Using a 10-point scale, each team member individually ranked how strongly we were achieving those missions. We quickly realized there were gaps between our mission statements and the actions we undertook that needed to be addressed.

Addressing the Gaps Between Mission and Action

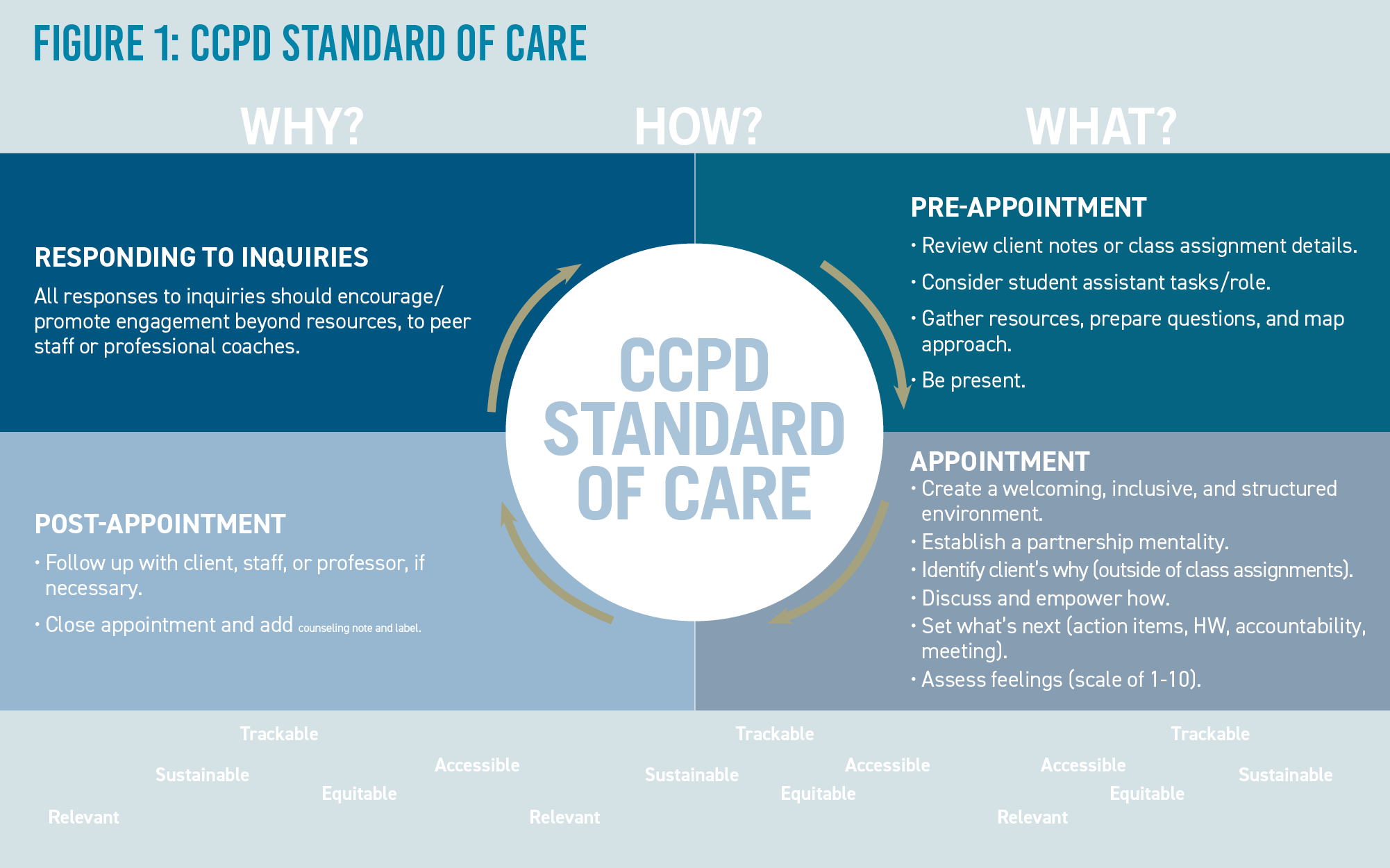

After many conversations, we landed on two methods to help address those gaps. The first was creating a “Standard of Care” to ensure that all students were served in a similar manner/process, no matter the staff member. (See Figure 1.) One example from the “Standard of Care” worth explaining is how we embodied the “why, how, what” model in our coaching strategies.

Most students enter our offices thinking they know what they want, e.g., to find an internship. Historically, our process would have encouraged that we teach them how to find an internship using strategies and resources. However, we didn’t always encourage the student to reflect on why an internship was important.

So, we flipped the model to start with why. As soon as the student indicated what they wanted assistance with—an internship, for example—our coach asked them to explain why they wanted an internship. This enabled the coach to assess the client's knowledge of the topic and introduce the benefits of an internship, such as the skill development an internship can afford. Then, the coach explained best practices in how we could support them in finding an internship and what was involved, such as their needing to update their resume and so forth. This simple adjustment helped our coaches educate our students and create simplified next steps.

The second, and perhaps most impactful, outcome of our strategic planning was TRESA:

- Trackable: Ensuring that we can obtain data to evaluate our educational resources and time allocation.

- Relevant: Ensuring educational resources and decisions are student-centered, efficient, effective, feasible, and applicable to office, university, and/or PASSHE mission and goals.

- Equitable: Ensuring all students have access to educational resources that meet their needs and help empower them to achieve their career goals.

- Sustainable: Ensuring educational resources can be used by students regardless of employee/peer staff turnover or attrition, or shifts in staff responsibility.

- Accessible: Ensuring educational resources are available to all students through in-person or online modalities.

TRESA was formed during the “why we do what we do” and “how we do it” processes. The evaluation of our mission showed gaps of equity and accessibility throughout our programs and services. TRESA was created to address those gaps and serve as a decision-making filter.

Now when I or a staff member have a new idea, our first step is to ask ourselves, “What does TRESA think?” Is the idea trackable? Is it relevant to our mission? Is it equitable, sustainable, and accessible to our students and staff? If the response to any of these questions is no, then it must be addressed before approval. This doesn’t mean every idea is implemented; rather, it means that TRESA empowers the team to examine their ideas and strengthen them before bringing them to the larger group for discussion.

We used TRESA to evaluate the last phase of our framework—what should we do/change. This process required the team to investigate our program and service offerings. Through many weeks of conversation, we identified 11 areas, which I have synthesized into four themes:

- Shifting the narrative from “career services” to “career development,"

- Providing robust hybrid/online educational resources,

- Increasing student employee usage and responsibility, and

- Prioritizing programs, services, and events and staff time.

Over the next few years, these themes served as our strategic framework and guided our decision making. Although each theme is important, the most ambitious theme—and the one our team had the least control over—was shifting the narrative from career services to career development. To put it bluntly, our team was (and still is) frustrated and disappointed that we are an optional university service for students. Most university staff and faculty viewed our work as transactional. I couldn't blame them—we operated that way and reinforced that view.

Our team wanted to change that perception and bring attention to the developmental process of a student’s career journey. We recognized that, if we truly wanted to help our students, we had to show stakeholders that our university model needed to shift from one-time transactions that often occurred later in the students' collegiate career to a development model that involved having career-related conversations earlier and more often.

Research tells us that faculty have a major influence on whether a student chooses to engage at their institution. However, our staff spent a significant amount of time in negotiating with faculty to involve them in our programs and services, e.g., by having staff present in the classroom and/or provide a career-related assignment. TRESA told us that this type of dependency on faculty was not (and is not) a sustainable model for us. In an effort to find a more sustainable model and to shift the narrative, we embarked on listening tours.

The Power of Listening to Elevate Career Development

Our team knew that change needed to begin with faculty and brainstormed various ways to pitch the concept of shifting the narrative. Historically, our approach to educating stakeholders was informing them of what we do and how we do it. Instead, we opted to start with why.

Of course, we did not sit faculty down and explain career development theory to them. Rather, we decided to ask key academic leaders and faculty one question and listen to what they had to say.

Our hypothesis was this: Faculty would be more likely to engage with the career center if we solved a problem they cared about.

This hinged on our being able to offer a meaningful question, one that could help us identify a problem/concern shared by faculty and the career center and determine if the career center could be part of the solution. If both were achieved, then we were confident that it would help systematically infuse career development into the curricular experiences and elevate career development within the campus culture.

To be honest, the question we really wanted to ask was, “Why do some faculty engage with us, and others don’t, even within the same department/college?” We knew, however, that such a question wasn’t going to work. In total, there were six steps in our listening tours—outlined below—and the first two helped us develop the question we ultimately posed to faculty: “What deficiencies do your current students and/or recent graduates have that you would like to see improved?”

There were six steps in our listening tours:

Step 1 – Meeting with the provost: I met with the provost to pitch the idea and get feedback and support for our listening tours. The provost offered her input on a meaningful question and put me on the agenda for the next Deans’ Council meeting.

Step 2 – Meeting with the Deans’ Council: I followed the same approach with the Dean’s Council meeting, and the deans further refined the question to make it “faculty friendly,” relatable, and usable. In addition, I asked to attend their next department chair meetings, which they agreed to.

Step 3 – Meeting with department chairs: The department chair level is where the magic happened. They were able to speak openly about their faculty—pros, cons, issues, and perspectives. They also suggested key faculty to follow up with and recommended that I engage with Clarion’s Center for Teaching Excellence to gather input. By far, this group was the most impactful and helpful. In addition, their response to our question provided robust data and insight.

Step 4 – Meeting with the Center for Teaching Excellence: My meeting with staff at the Center for Teaching Excellence confirmed the responses provided by the department chairs. It also helped to build awareness at the grassroots level of how the career center could help faculty with their problem. We later partnered with the Center to hold a workshop on how faculty could infuse the NACE competencies into their work.

Step 5 – Meeting with individual faculty members: I met with any faculty member who was available to gather their input. I also focused on and approached faculty who were non-engagers, those who historically did not or would not collaborate with our office. They were the ones we needed to win over. It was not easy getting a meeting, but having the support of the provost, deans, and department chairs helped to open doors that were typically bolted shut.

Step 6 – Synthesize findings and share with provost, deans, and department chairs: In all, the listening tours brought me one-to-one with more than 30 academic leaders. Our goal was to learn how we could embed career development into the curriculum across the university instead of the existing piecemeal approach.

What amazed me most about these listening tours was how consistent the answers were from all stakeholders, regardless of college or program. Faculty unanimously agreed that the deficiency they would most like to see improved in their current students and recent graduates was their soft skills—the career readiness competencies. Further investigation and clarification of this showed that they were not referring to a skills gap—it was an “articulation gap.” The issue faculty faced was that students were unable to connect how assignments and experiences supported their skill development, which led to poor articulation of the skill. Hence, the articulation gap. We knew from NACE and research that employers felt this way—but faculty, too?

At that moment, I knew we cracked our why with faculty and could be the solution.

Moving From Words to Action to Increase Campus Buy-in

Analysis of the listening tour allowed us to showcase how the career center was well positioned—and encouraged by NACE—to assist and empower students to identify, gather, and sharpen their career readiness competencies. Our next step was to move from words to action and create campus buy-in to show how the career center could help.

Thanks to a recommendation by department chairs during the listening tour, a dean and I co-led the development and coordination of a university-wide committee comprised of administration, faculty, and career center staff to investigate how faculty could embed the NACE career readiness competencies more visibly into their syllabi, class conversations, and assignments. The team worked for a semester to create and support four approaches.

Lesson learned

- Starting with “why” helped our office reset our thinking and grounded our approaches and decisions. It empowered staff to make clearer and stronger decisions and think innovatively about improvements.

- Shifting a culture takes perseverance and trial and error. Nothing happened overnight. It took deliberate focus and relationship building with key stakeholders and risk taking. It’s okay to fail forward.

- Advocate for a seat at the table—all of the tables—to ensure career development's voice is heard. If there is an administrative meeting you aren’t part of but should be, find a way to be included.

- Faculty partnerships create cultural shifts/changes—especially for optional services on our campus. Shared governance can make a difference, but start with the “unicorn” faculty who are the movers and shakers. They can shift the culture from the inside.

- Servant, authentic, and vulnerable leadership approaches helped our team feel welcomed, heard, and willing to try new things. Consider what leadership style you want to use, and—most importantly—take care of your team.

First approach

The first approach the committee focused on was brainstorming ways faculty could turn their syllabi to “skillabi.” We tasked faculty to take a current syllabus and look for ways to infuse the NACE competencies within their college and program learning outcomes and assessment materials. The results were astounding. Some faculty introduced the NACE competencies and linked to additional resources, others visibly showed which NACE competencies connected to their program and learning outcomes, and some faculty went as far as revamping their assessment materials with the NACE competencies. Most did all the above!

The faculty shared their “skillabi” examples with the committee and conversations continued, but this time by considering best practices in how to intentionally verbalize and connect the competencies during lectures. As one faculty member noted, these “competencies need to be prevalent in our everyday lectures.”

The outcomes of this first approach were shared with the department chairs, deans, and Center for Teaching Excellence staff for dissemination and follow-up workshops.

Second and third approaches

The second and third approach scaffolded together nicely and focused on actions the career center could take. To elevate the NACE competencies further and address stakeholders’ articulation concern, we updated our resume checklist and created a new interview rubric to be more visibly inclusive of the NACE competencies. The resume checklist helps students understand the difference between simply listing a skill and clearly articulating the skill. (See Figure 2.) Our interview rubric evaluates the student’s ability to understand, identify, and articulate an experience representative of each of the NACE competencies. (See Figure 3.) It was built to allow anyone, but preferably an alumnus or employer, to pick up the rubric and assess the student’s career readiness during a practice interview.

Fourth approach

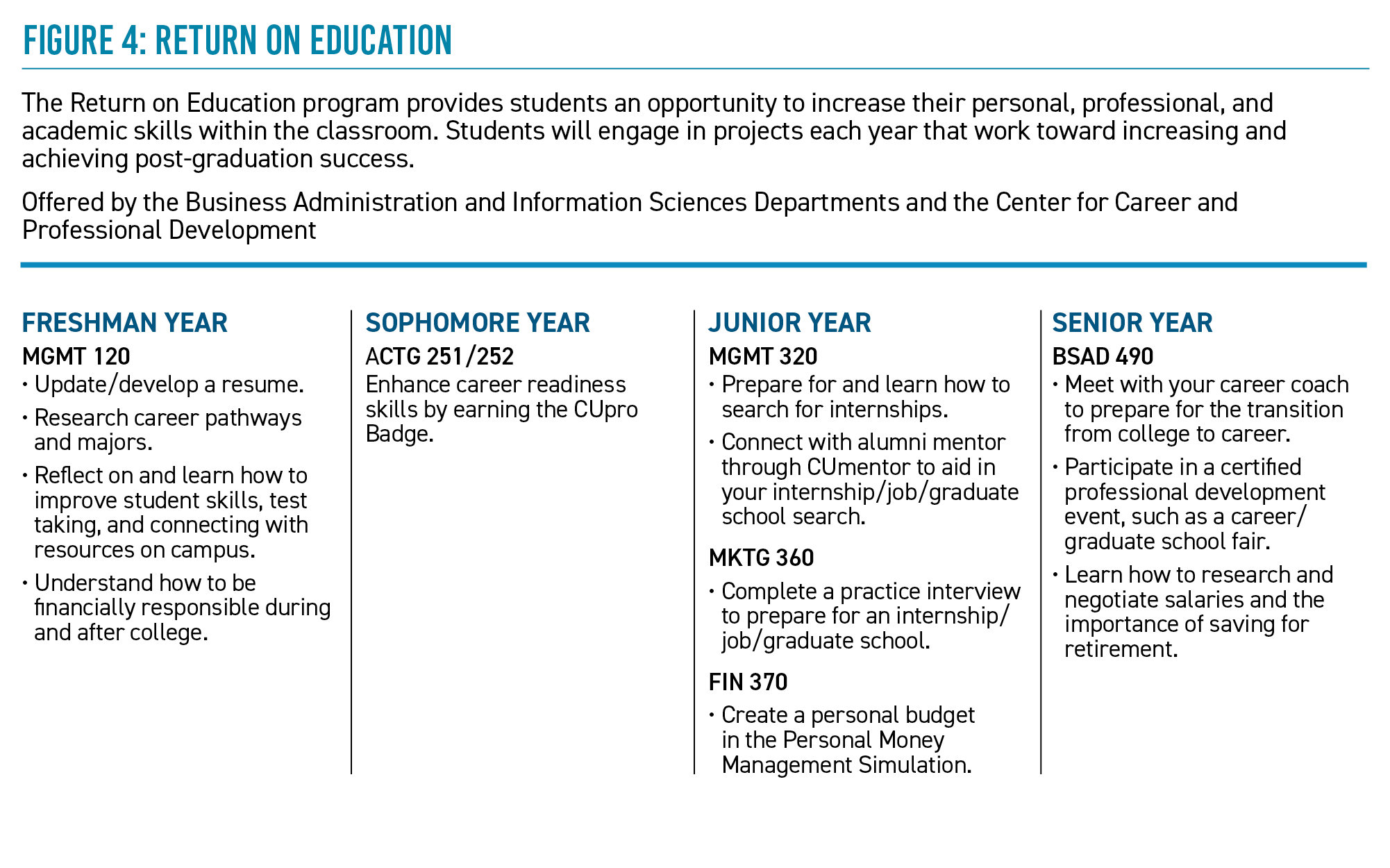

The last approach the committee discussed was continuing to educate academic stakeholders on the career center’s four-year career and professional development plan. The rebranded plan, titled “Return on Education,” showcases how the career center educates, empowers, and supports students’ career competency attainment and articulation, which has led to faculty adoption and embedding into the curriculum. (See Figure 4.) The plan outlines how faculty can learn where and how the career center can engage in the curriculum and leverages gamification to support and motivate student engagement. (Editor’s note: For more on the gamification and career readiness, see Domitrovich’s “Creating a Mentoring Program: Using Gamification to Increase Students’ Career Readiness and Graduation Outcomes,” which appeared in the February 2020 issue of the NACE Journal.)

*****

The four approaches outlined above strengthened the visibility of our career center among academic leadership and helped elevate the importance of career readiness at Clarion. Although we did not know it at the time, it also laid the groundwork for our integration planning when Clarion, California, and Edinboro merged to become PennWest. Further, the work we did also helped us with our initial strategic plan for PennWest, as career readiness is one of the plan’s eight pillars.

We have a long way to go at PennWest, and a whole host of new challenges, including managing budget and staffing reductions, serving three distinct locations as well as online students, and being relocated to strategic enrollment management. These approaches helped close a significant gap for our future students' career readiness, but we are just getting started! We’ll keep fighting the good fight: I hope our approaches can help you do the same.