NACE defines an internship as a form of experiential learning that integrates knowledge and theory learned in the classroom with practical application and skills development in a professional workplace setting (across in-person, remote, or hybrid modalities). Internships provide students the opportunity to gain valuable applied experience, develop social capital, explore career fields, and make connections in professional fields. In addition, internships serve as a significant recruiting mechanism for employers, providing them with the opportunity to guide and evaluate potential candidates.

Since 1956, the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) has connected tens of thousands of career services and early talent recruiting professionals, serving as the authority on the employment of the college educated.

We forecast annual hiring trends, identify best practices, track student outcomes, and provide extensive professional development opportunities.

SEE WHAT NACE HAS TO OFFERInternships are routes to jobs for job seekers and access to talent for employers.

For job seekers, NACE research demonstrates that work-based experiences can be avenues to increased skills, expanded networks, and enhanced social capital. Internships—particularly paid internships—are also direct pathways to job offers. According to the results of the NACE 2022 Student Survey for four-year college students, paid interns averaged 1.61 job offers, compared to 0.94 offers for unpaid interns, and 0.77 offers for non-interns.

For employers, internships are one of the main recruiting tools employers use to recruit entry-level college graduates. According to a recent NACE quick poll, eight out of ten responding employers said that internships provided the best return on investment as a recruiting strategy, compared to career fairs, on-campus visits, on-campus panels, or other activities (NACE Winter 2022 Quick Poll: Spring Recruiting and Career Services).

Internships serve as an important bridge from college to career. NACE research has demonstrated that internship experiences are avenues to increased skills, expanded networks, and enhanced social capital, and offer direct pathways to job offers and jobs. While many internships are paid, unpaid internships are problematic for many reasons. Using an equity lens, NACE’s position statement on unpaid internships is a call to policymakers to address the inherent inequities unpaid internships cause and to work to ensure all internships are paid.

Read the Position Statement

Yes, currently unpaid internships are legal in certain situations. Based on a test developed by a federal court, the U.S. Dept of Labor has released a fact sheet that outlines the Primary Beneficiary Test (PBT), which should be used to determine who benefits primarily from the internship. In general, if the student/intern is the primary beneficiary, then the unpaid internship is legal; if the for-profit company is the primary beneficiary, the intern must be paid. Not-for-profit organizations and government agencies are exempt from this regulation.

Yes—legally, not-for-profit organizations and government agencies can offer unpaid internships, according to the FLSA. However, if they do not pay their interns, they must recognize that their intern cohort will include those who can afford to forgo a paycheck or are willing to endure financial hardship while providing unpaid labor.

In cases where not-for-profits and government agencies cannot afford to pay their interns but would still like to provide experiential learning opportunities to students, they should seek to ensure their interns are compensated in some fashion. For example, local chambers of commerce or universities may offer funding for low- or unpaid internships.

Budgets reflect priorities, and if developing and diversifying the government workforce of the future is a priority, then government offices should make the investment now. It is NACE’s position that all internships should be compensated in some fashion and for this to occur, government agencies—both local and federal—must lead the way.

Although the PBT does not explicitly state that academic credit is compensation for the internship, this perception has been an unintended consequence of its inclusion as Factor #3 in supporting an unpaid classification for the internship. This implies that academic credit functions as a type of compensation. Indeed, some employers justify unpaid internships because students “are earning class credit instead.” However, in nearly all cases, students purchase those academic credits, and compensation for labor cannot be purchased by the laborer. Therefore, NACE takes the position that academic credit alone is insufficient as compensation and should not be used to justify an unpaid internship. NACE stresses that being compensated should not preclude students from earning academic credit. There is no reason why a student cannot earn credit, which they purchase and work toward by accomplishing academic goals, and monetary compensation for the labor they contribute to their internship employer.

Absent any law precluding unpaid internships, this is a policy decision for the institution and career center. NACE takes the position that, while unpaid internships can be valuable, they are a source of inequity; therefore, institutions and career centers are encouraged to consider how to reduce the practice until such time as unpaid internships can be ended.

To determine whether to post the unpaid internship or not, career centers should ask: Will this unpaid internship provide an irreplaceable stepping-stone for this student in reaching their ultimate career goals? In answering the question, career centers should weigh the value of the unpaid internship position in its ability to help students explore career paths, develop professional networks, and confirm their career goals against the amount of time and labor required for the internship. NACE encourages career centers to have very high expectations for the unpaid internships they choose to post.

NACE encourages career centers to help organize various funding streams that can be used to help support low- and unpaid internships. Federal work study funds, funds available pursuant to the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), institutional stipend funding, and local chamber of commerce funding are options to consider to eliminate unpaid internships.

According to results detailed in the NACE 2022-23 Career Services Benchmark Report, about 35% of colleges and universities reported offering a stipend program for low- and unpaid internships, but only 2.1% provide the stipends for any and all unpaid or low-paid internships; most of the programs require the student to apply for competitive and limited funding.

Although institutions administer these programs variably, they are generally a quick and efficient way of getting money into interns’ hands. These stipend programs should be supported by the government and industry, not just donors and institutions of higher education as is most common now; they should be extended to more students and increased in amounts.

NACE conducts annual surveys and various quick polls to get the pulse of what's happening in the field.

SEE ALL OF OUR RESEARCHNACE supports several pieces of federal legislation:

NACE research found that all college students are not equitably represented in internships (Inequity in Internships, NACE, 2021). According to survey data provided directly by students, women, Black, Hispanic, and first-generation students were underrepresented in paid internships. In 2022, NACE analyzed internship data from 187 employers, and the findings were nearly identical. Again, women, Black, and Hispanic students were significantly underrepresented as a proportion of paid interns.

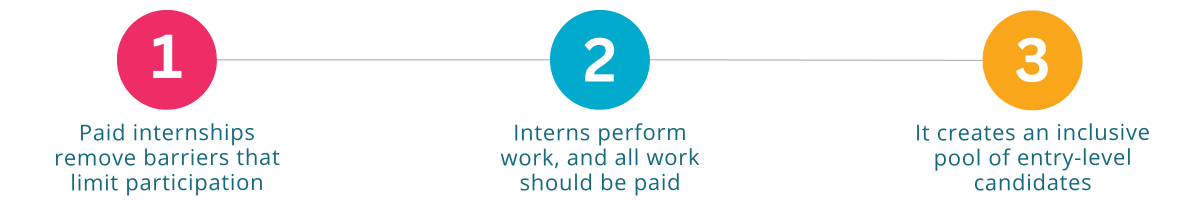

Taken together, the research shows that white, male, and continuing-generation students are disproportionally represented in paid internships. The current bifurcation of paid and unpaid internship opportunities is leading to a disparate impact on student outcomes. Because paid internships are disproportionately going to men, white students, and continuing generation students, these students then go on to receive more job offers and higher starting salaries, which compounds the disparate impact over time.

Providing paid internships or, at the very least, providing supplementary funding through WIOA funds, federal work-study, stipends, and similar sources for under- or unpaid internships are the two most immediate solutions to these inequities.

Additionally, though challenging, there is a legislative path that can bring more equity to the internship space. This legislation would have to revise or reject the PBT and replace it with guidance that interns must be paid. The White House voluntarily converted its unpaid internships to paid ones, and the 117th Congress passed a law requiring paid internships at the U.S. State Department, and we encourage others to follow suit.

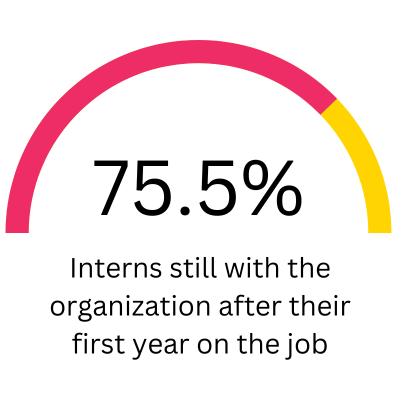

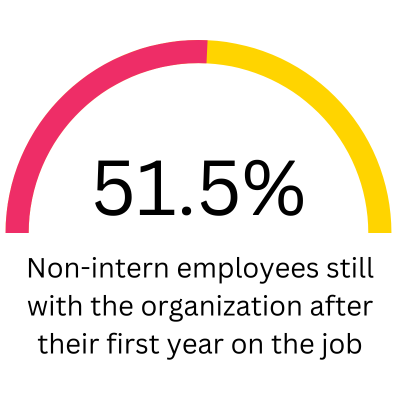

Internships are one of the main recruiting tools large employers use to recruit entry-level college graduates. As part of their strategy, employers strive to convert a large proportion of their student interns to full-time employees. Moreover, interns who become employees are retained at higher rates than other hires: 75.5% are still with the organization after their first year on the job compared to 51.5% of non-intern employees (NACE 2023 Internship & Co-op Report, 2023). Thus, if internship programs are paid and therefore accessible to a wider, more inclusive pool of candidates, then they can be an effective way of directly influencing the diversity of the company’s incoming cohort of early career individuals. In short, if all internships were paid, employers would be better equipped to recruit a diverse internship cohort and resultant workforce.

Experiential learning is an umbrella term for various types of work-based experiences that usually take place outside the classroom, but which build on, complement, and/or supplement the academic learning that takes place inside the classroom. The various types of experiential learning include, but are not limited to internships, co-ops, apprenticeships, externships, practicum/clinical/field placements, job shadowing, on- or off-campus original research projects, and on-campus work study jobs.

Cooperative education programs, or co-ops, provide students with multiple periods of work in which the work is related to the student’s major or career goal. The typical program plan is for students to alternate terms of full-time classroom study with terms of full-time, discipline-related employment. Because the program participation involves multiple work terms, the typical participant will work three or four work terms, thus gaining a year or more of career-related work experience before graduation. Virtually all co-op positions are paid, and the vast majority involve some form of academic credit.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, apprenticeships combine paid on-the-job training with classroom instruction to prepare workers for highly skilled careers. Workers benefit from apprenticeships by receiving a skills-based education that prepares them for good-paying jobs. The federal government supports the Registered Apprenticeship Program (RAP) to help employers and job seekers alike. For more information about the RAP, see www.apprenticeship.gov/employers/registered-apprenticeship-program.

Published June 2023