NACE Journal, November 2020

Internships have long been viewed by students, employers, and career services professionals as a boon to the job search, recruiting, and career development, providing value to all.

For students and career services professionals, internships offer a range of benefits, including the opportunity to identify and clarify career direction, develop skills important to career readiness, and gain first-hand experience in the workplace. For employers, internships can serve as a valuable source of new hires, enabling the organization and potential hire to try each other out, thereby enhancing retention down the road as well.

Paid Internships and Exclusivity

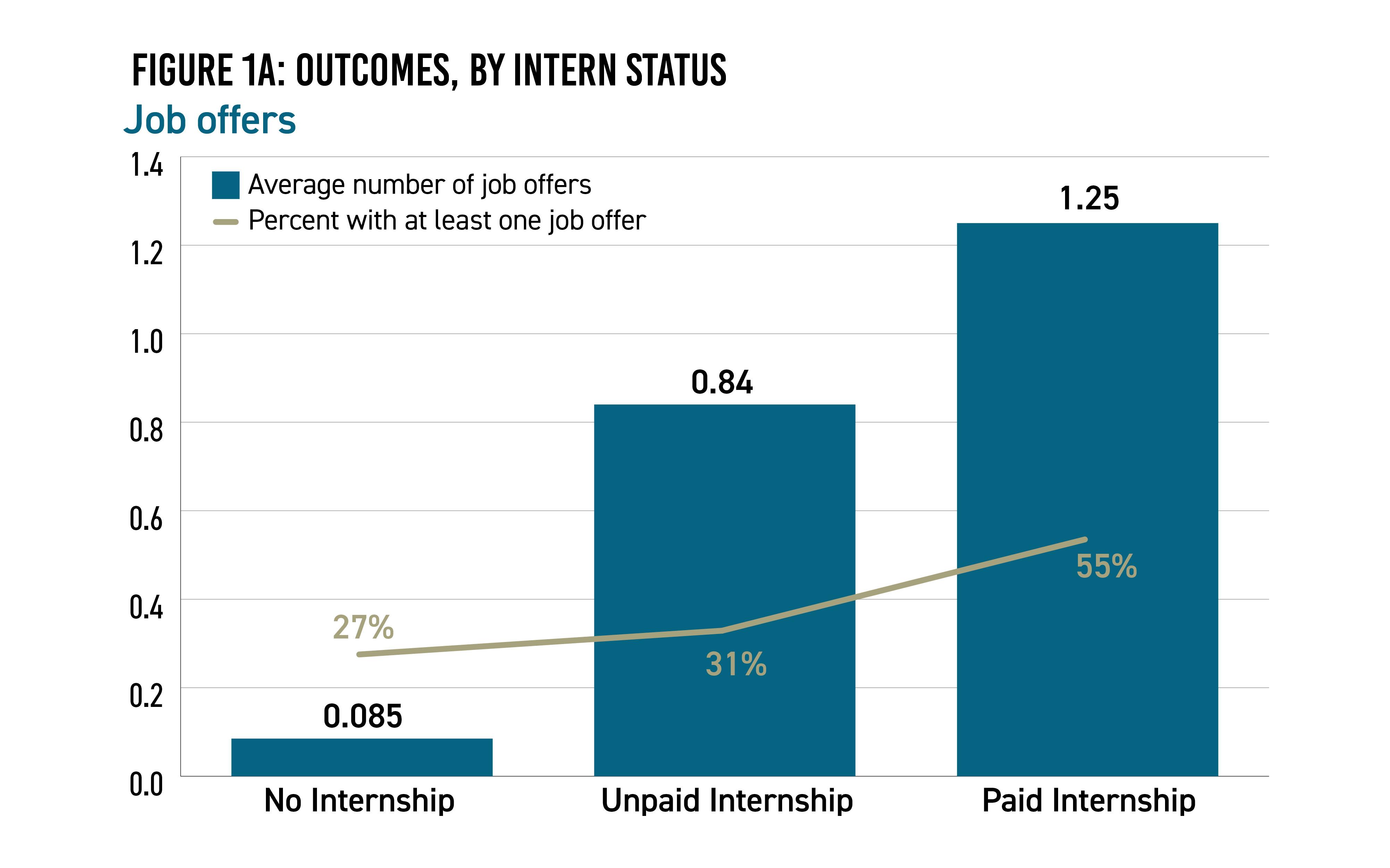

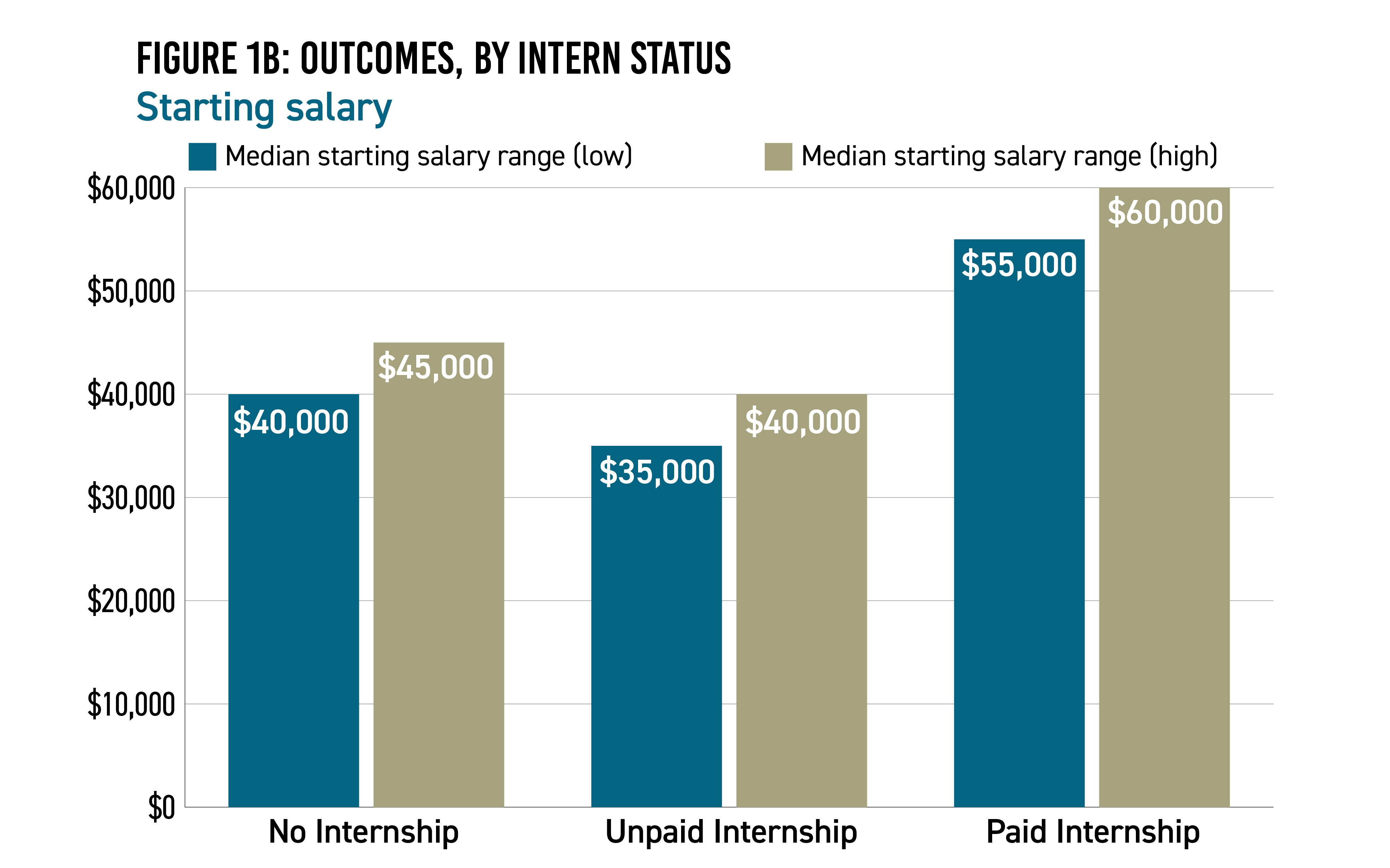

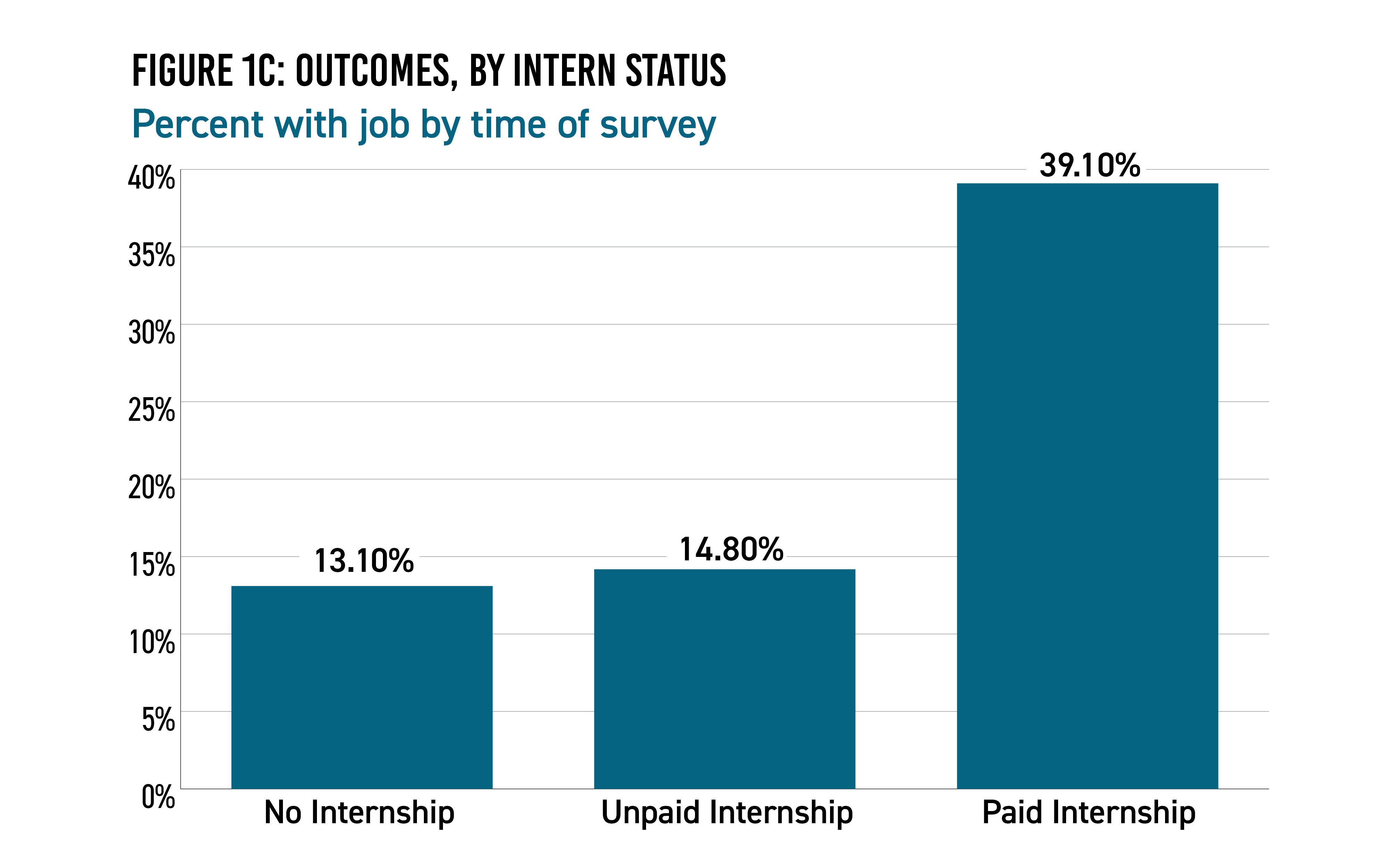

While all types of internships can have value, NACE research has found that paid internships benefit students in their job search in multiple ways, at least in terms of the first job post-graduation: more job offers, higher starting salaries, and a shorter search.1 (See Figures 1a, 1b, and 1c.)

Employers interested in leveraging their internship programs to feed full-time hiring typically pay their interns, which allows them to give their interns “real work” and thus a real crack at showing their abilities. The practice of paying interns is also supposed to support the quality of the candidate pool, ensuring that the opportunity is open to everyone, not just those able to forgo a paycheck for the summer.

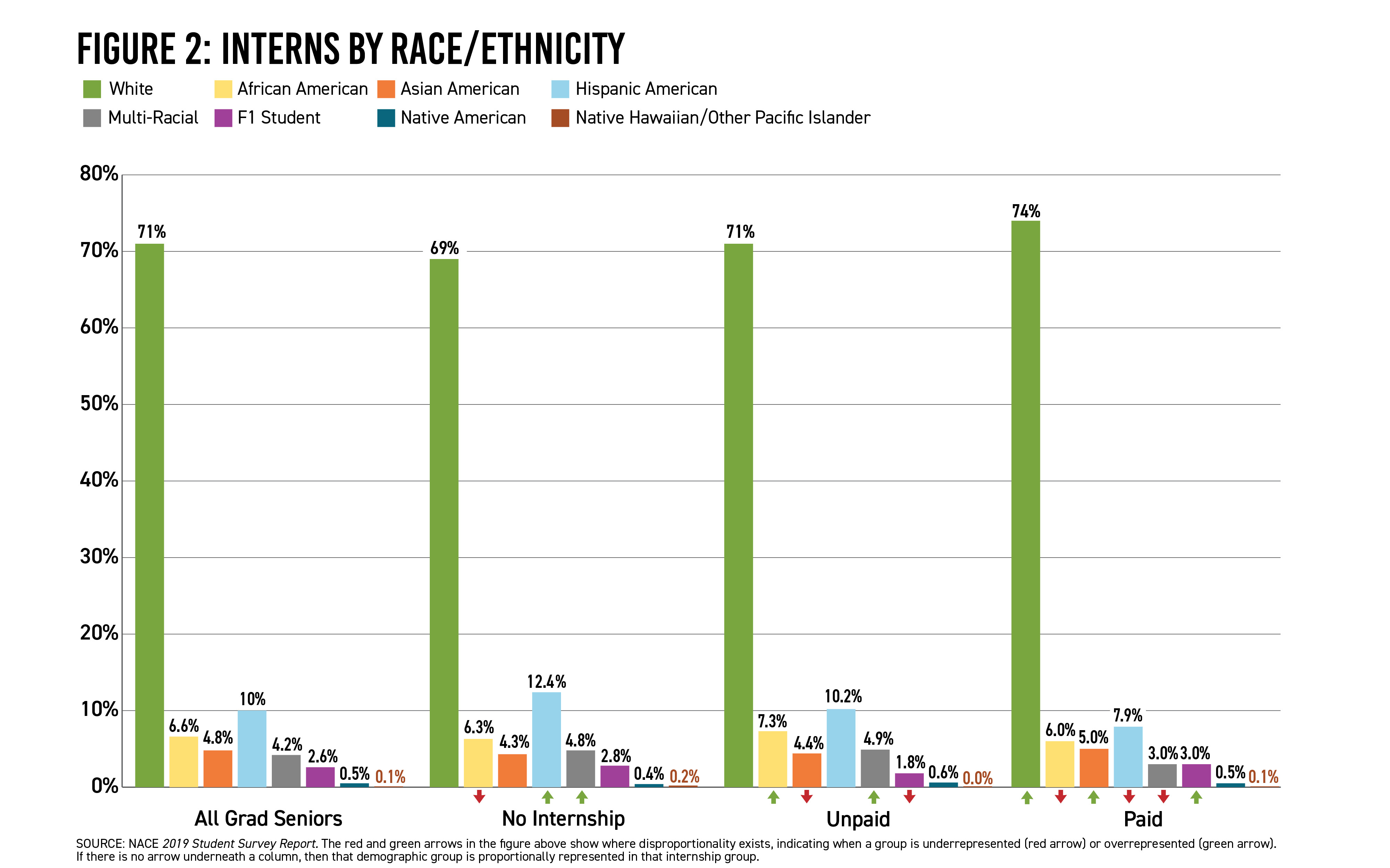

At the same time, however, analysis indicates that this path to employment may be exclusive. Data collected through NACE’s annual student survey indicate that racial/ethnic minorities, women, and first-generation students are all underrepresented in paid internships. This door, figuratively speaking, to a first job post-graduation is shut.

For example, Black students accounted for 6.6% of the nearly 4,000 graduating seniors who took part in NACE’s survey.2 However, just 6.0% of paid internships went to Black students. Instead, Black students are overrepresented in unpaid internships, accounting for 7.3%. The same scenario plays out for Hispanic-American students and students who identify as multi-racial. (See Figure 2.)

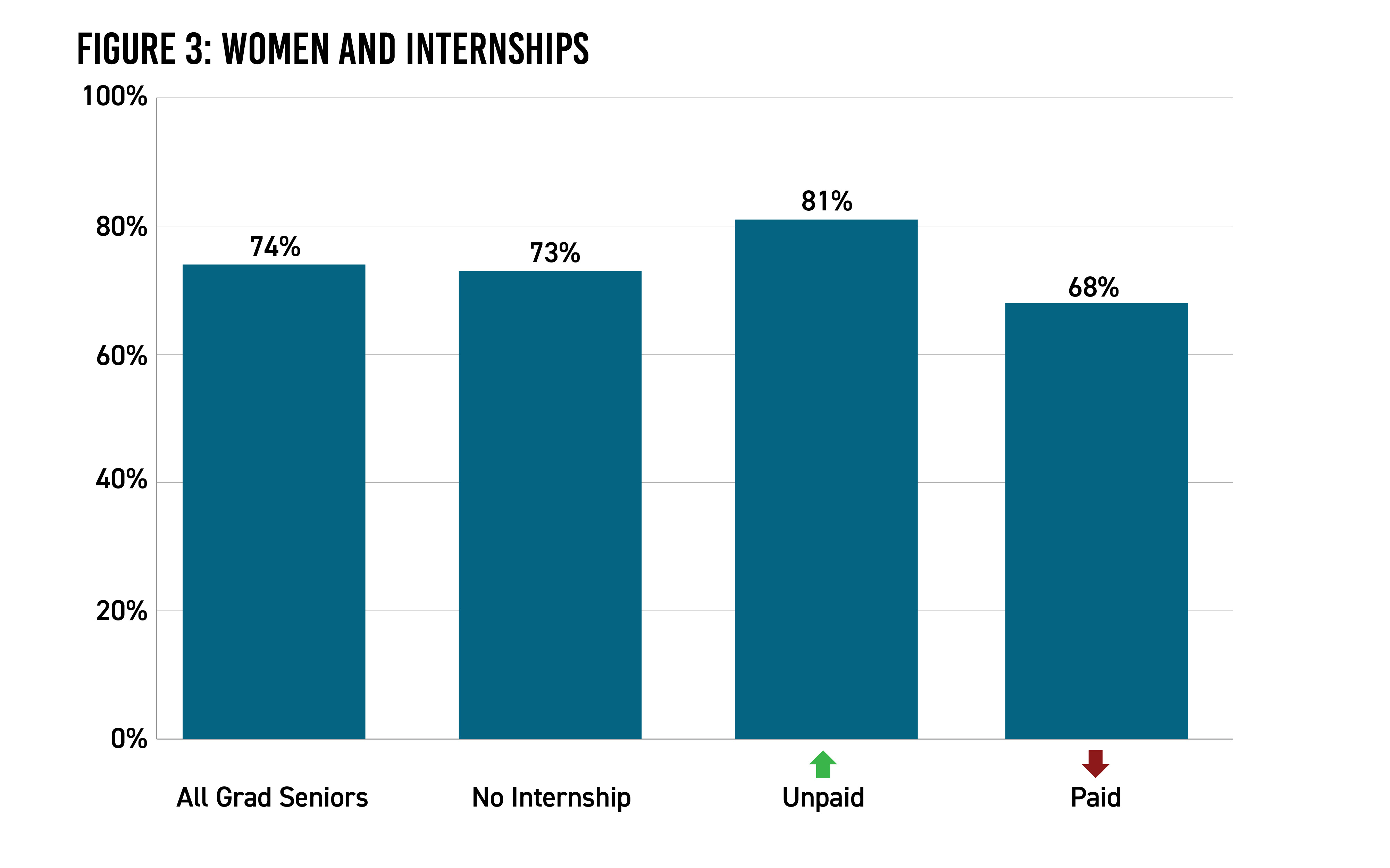

Women, who account for nearly three-quarters of all graduating seniors in the survey, make up just 68 percent of paid interns. As is the case with racial/ethnic minorities, women make up a disproportionally larger share of unpaid internships. As Figure 3 shows, the “brightest” data for women indicate that, although they did not get paid in proportion to their numbers, they did, at least, engage in internships…

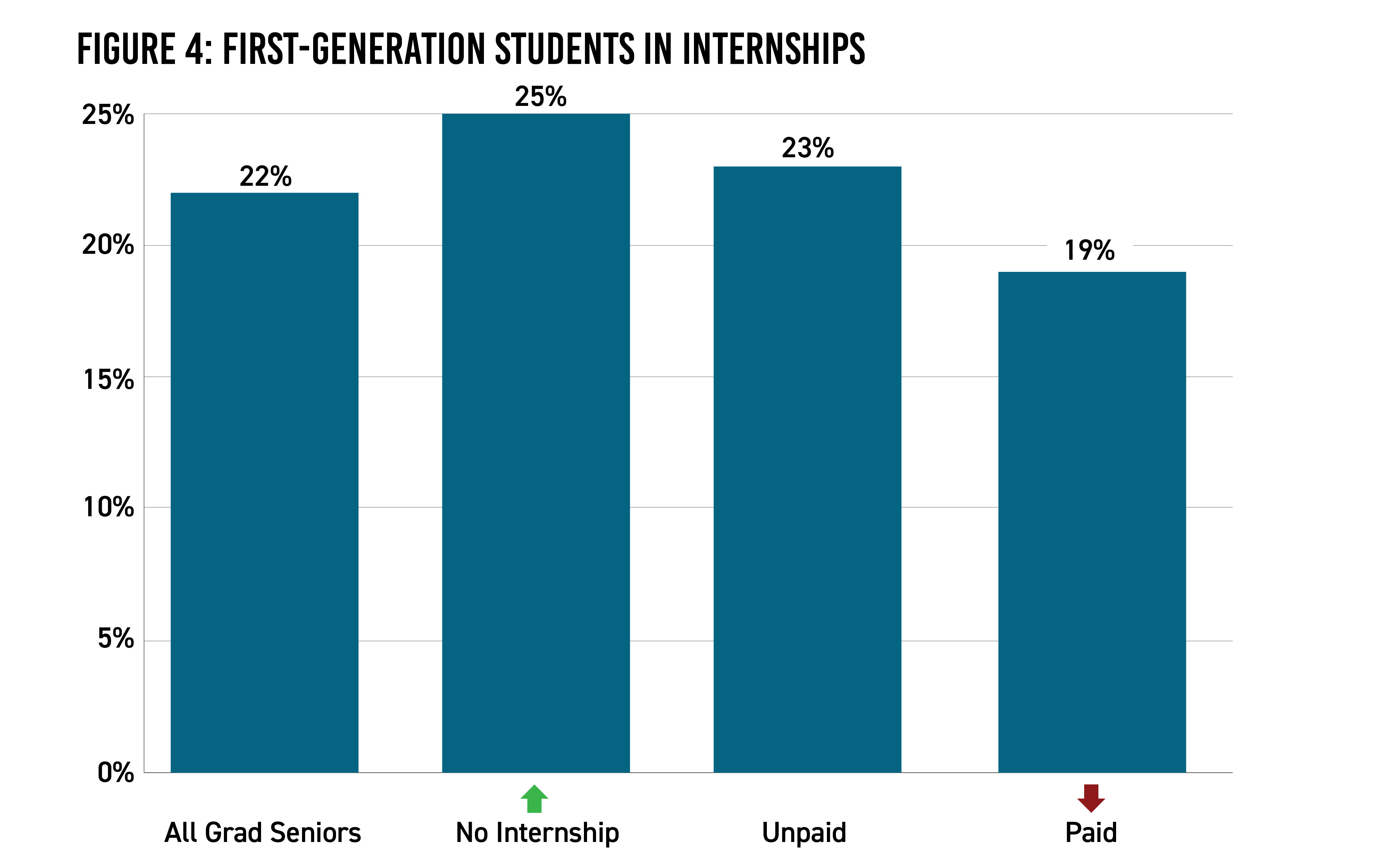

…unlike first-generation students, who are disproportionally represented among students who have never taken part in an internship.3 (See Figure 4.) Further, as was the case with racial/ethnic minorities and women, first-generation students are underrepresented in paid experiences.

Recommendations for “Opening the Door”

At this juncture, we do not have a clear understanding of why women, racial/ethnic minorities, and first-generation students are underrepresented. The NACE study was limited, so its takeaways point broadly to the issue but are less helpful in narrowing down causes. Likely there are a variety of contributing factors that warrant exploration.4 Despite the lack of granular information with which to pinpoint and work to resolve problems, there are actions employers can take to ensure their own programs are representative of the larger pool of candidates.

Track intern demographics: This is common practice among employer organizations with well-defined internship programs, but bears mentioning regardless, especially if your internship program is s key feeder for full-time hiring.

Consider how you source interns: If efforts are concentrated on a set of schools, then the overall demographics of those institutions determine your potential intern pool. Look at how you can open that up to expand your pool beyond those schools.

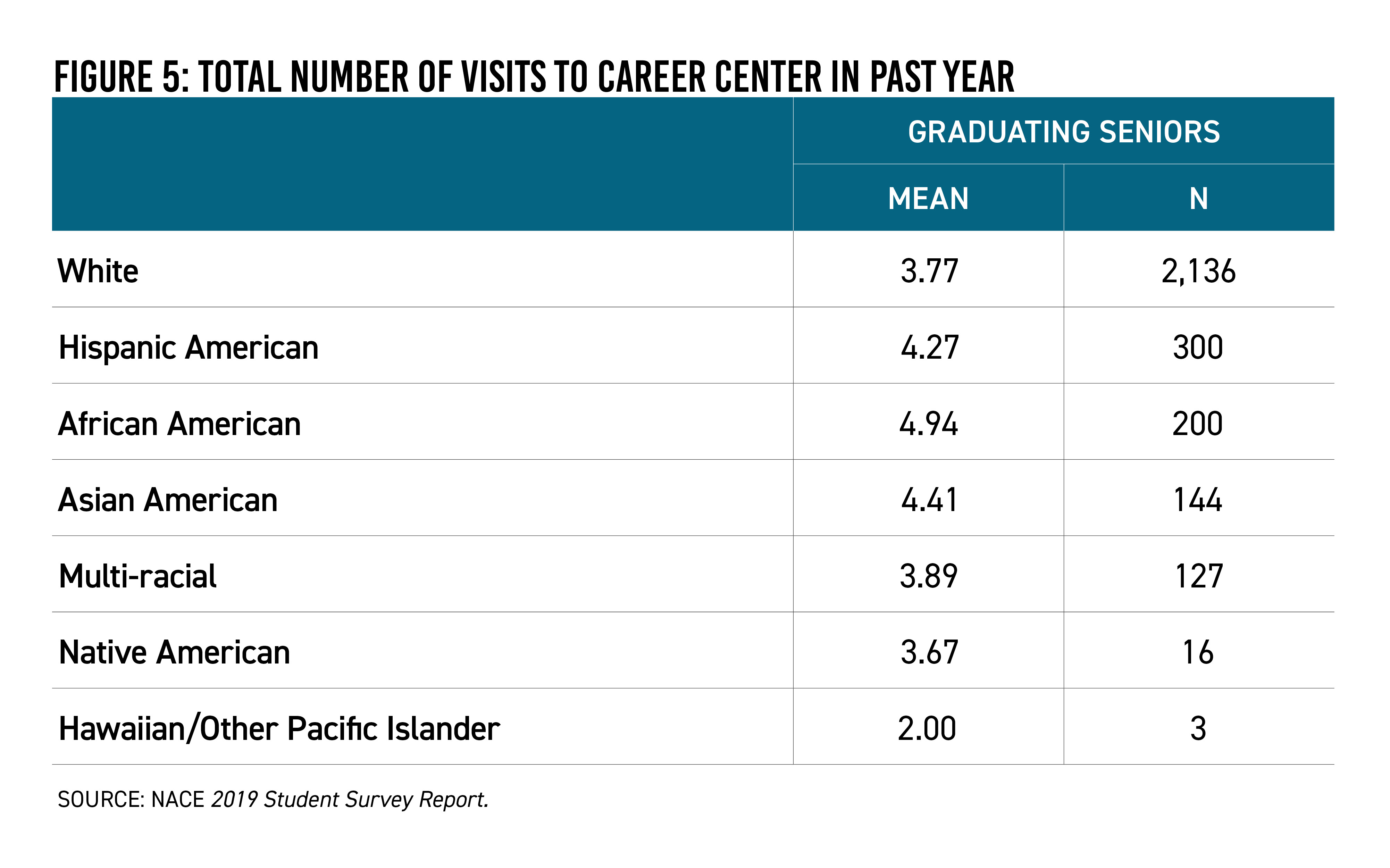

Work with career centers: Data indicate that, overall, Black students use the career center more than other races/ethnicities, not only in number of total visits, but also proportionally.5 For example, 41% of white graduating seniors reported using the career center while 55% of Black graduating seniors did so. (See Figure 5.)

The takeaway: The career center is an important resource for organizations looking to reduce inequities and expand their candidate pools for internships as well as full-time positions.

Work to identify barriers in your systems: For organizations, one place to start is your selection criteria. For example, is GPA a significant factor, and why? Can you tie a specific GPA to performance? Who does it cut out? Are there mitigating factors that could be taken into account if a candidate does not meet your GPA threshold? Along the same lines, review the other screening mechanisms and tests you have to determine who is being screened out—and why.

Endnotes

1 National Association of Colleges and Employers (October 2019). 2019 Student Survey Report (Four-Year Colleges). The data, derived from NACE’s 2019 Student Survey, were collected from February 13, 2019, through May 1, 2019. A total of 22,371 college students responded from 470 NACE-member colleges and universities across the country. The focus of the report and the data presented here is on the experiences of the 3,952 graduating seniors who participated.

2 Ibid.

3 First-generation status is defined in this study as a student whose parents have not earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

4 One of the limitations of the analysis is that the students’ majors were not taken into account.

5 National Association of Colleges and Employers (October 2019). 2019 Student Survey Report (Four-Year Colleges).