NACE Journal, November 2019

For much of America, the Great Recession of 2008 is a distant memory. Basic economic indicators such as unemployment have been favorable for several years. Average wages have been on the rise.1 The overall economy is strong, but the national employment numbers mask a different reality for rural states like West Virginia. Between 2013 and 2018, West Virginia lost 20,000 jobs, while the overall job market in the United States increased by 15 million positions.2 In the state capital of Charleston, home of the University of Charleston (UC), the population fell by 1.6 percent in 2018, more than any other metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in the nation.

Of the 20 MSAs that lost the most population last year, six are in West Virginia.3 This alarming trend has contributed to a weak economy in the Mountain State, which has resulted in fewer places for college graduates to work. There is strong evidence that metropolitan areas are magnets for college-educated people,4 which hurts states like West Virginia where there are no major cities. This results in a negative employment feedback cycle. Businesses want to locate in areas where qualified talent is plentiful, but educated workers are often attracted to areas that already have strong economies.

Reevaluating Employer Partnerships

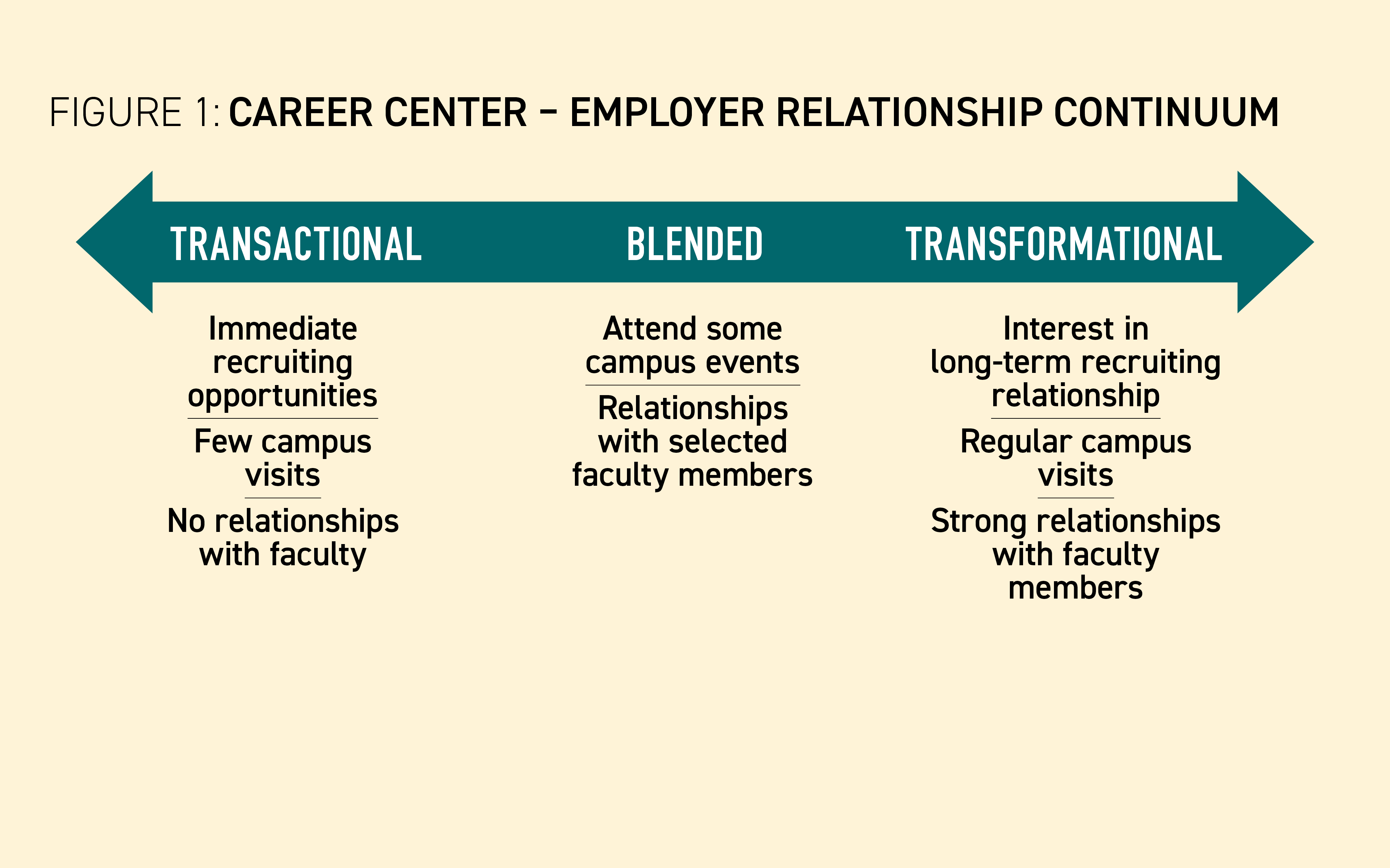

At the University of Charleston Center for Career Development (CCD), we have battled the economic challenges in the state by reevaluating our approach to employer partnerships. Since we have not been able to rely on a steady stream of new employment opportunities for our students, we have had to make the most out of our existing partnerships. We discovered that our strongest employer relationships are characterized by the following:

- The organization provides well-defined structured internship opportunities;

- The organization is visible on campus, attending networking and recruitment events regularly;

- Recruiters and hiring managers get to know students personally; and

- Recruiters form strong relationships with the faculty members as well as the Center for Career Development.

Conversely, our weaker, less fruitful employer relationships are characterized by the following:

- The organization has poorly designed internship opportunities with unclear expectations;

- The organization makes very few, if any, visits to campus;

- There is little to no effort to interact with faculty members; and

- The organization has a transactional approach to recruiting. (We define a transactional approach to recruiting as one in which the organization isn’t willing to participate in activities unless the activities provide immediate referrals to candidates. For example, we host an event at UC called the “I-3 Innovation Showcase.” We rely on our employer partners to serve as judges for various innovation competitions. This rarely results in immediate applications from students, but it often boosts the reputation of the organization with students and faculty.)

The relationship between career centers and employers can be envisioned as a continuum with “transactional” on one end and “transformational” on the other. (See Figure 1.) It may not be possible to interact with every employer in a significant way, but, for rural schools, it is critical to move as many employer relationships as possible to the transformational side of the continuum.

Transforming Transactions to Relationships

In the 2016-17 school year, we began shifting our approach to employers from transactional to transformational. Using the information gleaned from our analysis of our most and less fruitful relationships, we developed more opportunities for employers to visit campus and created business-facing brochures to let employers know the different ways they could interact with us. Perhaps most importantly, we focused on building stronger relationships between faculty members and corporate recruiters. We recognized that, although some organizations are eager to get involved on campus, corporate recruiters typically are not experts in dealing with college students. Career center staff members understand how to reach students and can help employers, but there are limitations. At the University of Charleston, we recognize that our faculty members are better connected with students than CCD staff members. We leverage those relationships by asking faculty members to promote our events and by connecting those instructors with corporate recruiters.

How has this shift impacted the CCD?

A key measure for us in assessing the health of our employer relationships is internships. First-destination data are important, but do not always provide a clear indication of the success of our employer relationships. For example, many students pursue graduate school after completing their programs at UC, which is not indicative of the school’s relationships with employers. We also have many out-of-state and foreign students who seek jobs closer to home following graduation. Credit-bearing internships, however, are directly related to our relationships with local employer partners.

Since the 2015-16 school year, we have experienced a 116 percent increase in credit-bearing internships. In fact, from 2017-18 to 2018-19, we saw a 23 percent increase in credit-bearing internships obtained by our students.

In addition to increasing internships, the transformational approach to employer relationships has produced more total employer relationships for our career center. CCD staff members are more active in pursuing employer partnerships, and faculty members are now more involved in the recruitment of employers. Over the past year, we increased the total number of relationships with in-state employers by 82 percent. Of course, many of those relationships could be classified as “transactional” or “blended,” but the process of developing transformational employer relationships looks something like a funnel—you start with several potential relationships to end up with a few transformational ones. Not all employer relationships are well-suited for higher maintenance transformational relationships.

Most of our new employer relationships are with existing businesses that have not previously worked with UC, not from new businesses. (As noted above, West Virginia lags behind in new business growth; consequently, we must make the most of partnerships with existing organizations. )

Our approach can be replicated in any area, rural or urban. However, it is imperative for rural colleges to be proactive in partnership development. There simply aren’t as many employment opportunities in rural areas as there are in larger metropolitan areas.

The UConnect Employer Partnership

Starting with the 2019-20 school year, we branded our transformational employer relationship model as the “UConnect Employer Partnership.” We developed literature and a social media campaign that explicitly stated the benefits of working closely with the CCD. We ask employers to make three simple commitments: 1) Provide at least one structured internship, 2) provide at least one employee to serve as a student mentor during the school year, and 3) attend campus events on a regular basis.

In return, we list our UConnect partners on our website, invite UConnect partners to be regular guests on a podcast series we recently launched, host a semi-annual reception for UConnect partners, and host an annual “UConnect Partnership Forum” to discuss solutions to our partners’ most pressing talent development issues.

Employer partnerships have always been an important part of college career centers. According to NACE, employer partnerships are on the rise, but are most common among major research institutions.5 Rural colleges—especially smaller schools like the University of Charleston—stand to benefit the most from transformational employer relationships. A local employer once shared with me that it was not worth his time to post jobs on colleges’ job boards, but he could always find time to connect face-to-face with students. The transformational employer relationship model is a simple, but effective, way to link students with employers, thereby leading to job opportunities in areas where they are needed most.

Endnotes

1 Bureau of Labor Statistics. Real Average Weekly Earnings Up 0.8 Percent From July 2018 to July 2019. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2019/real-average-weekly-earnings-up-0-point-8-percent-from-july-2018-to-july-2019.htm

2 Lego, B., Deskins, J., Bowen, E., Christiadi, Atkinson, M. West Virginia Economic Outlook 2019-2023 (2018). Bureau of Business & Economic Research. 302. Retrieved from https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/bureau_be/302

3 Census metro data calculated from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2018_PEPANNRES&src=pt

4 U.S. Congress Join Economics Committee. Losing Our Minds: Brain Drain Across the United States. Retrieved from https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/4/losing-our-minds-brain-drain-across-the-united-states

5 National Association of Colleges and Employers. “Employer Partnership Programs Becoming More Common,” Spotlight newsletter, June 12, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.naceweb.org/career-development/organizational-structure/employer-partnership-programs-becoming-more-common/