NACE Journal / Spring 2024

In winter 2024, NACE surveyed its membership to better understand their experiences in the profession. NACE’s Career Progression in Career Services and University Recruiting Quick Poll, sent to 15,024 NACE members, focused on how professionals progress in career services and university recruiting, along with the barriers to and supports for successful career pathways in the profession. The survey was fielded from February 20, 2024, to March 15, 2024. Overall, there were 1,727 responses, of which 87.6% were college members, 11% were employer members, and 1.4% represented other types of members.

Reasons Professionals Enter Career Services and University Recruiting

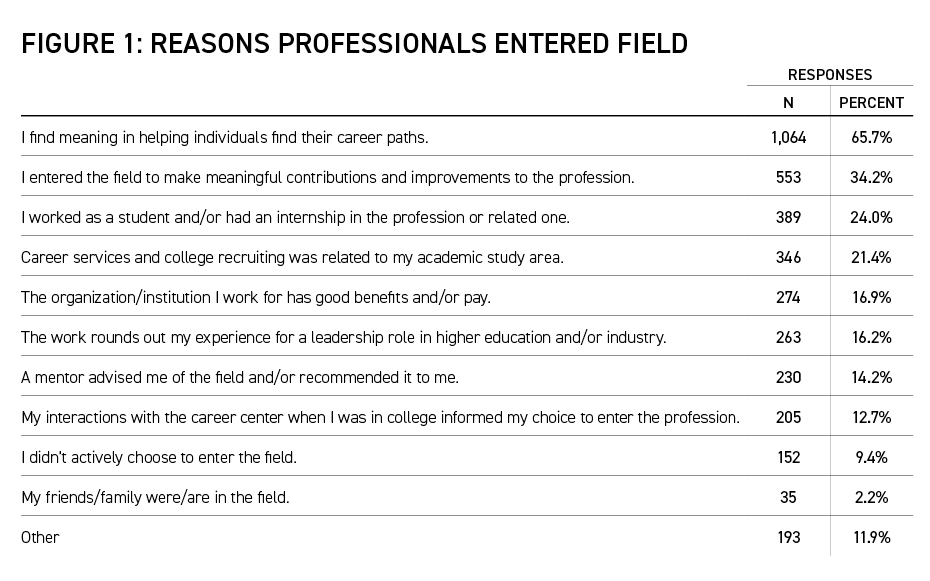

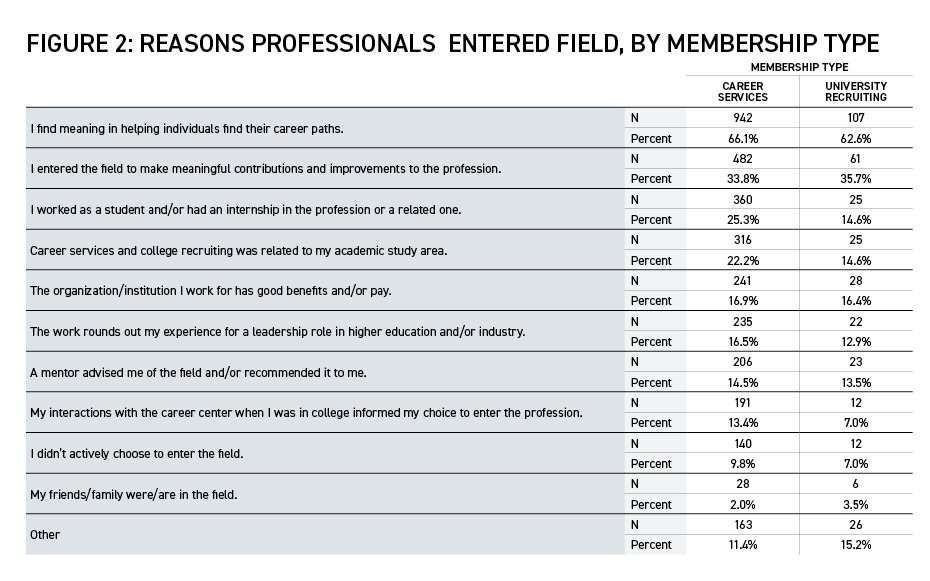

By far, and regardless of membership type, career services and recruiting professionals are drawn to the field because they find meaning in helping individuals find their career paths.

Overall, two-thirds of members reported that this was a reason why they entered the field. There is very little difference between members who work for colleges and those in industry (66% of college members versus 63% of those in industry). Following this, more than one-third of respondents reported they entered the field to make meaningful contributions and improvements to the profession. (See Figure 1.)

Other reasons that professionals entered the field included awareness of the field that they gained during college. For example, almost one-quarter of respondents had an internship or worked in the profession, more than one-fifth reported that career services and college recruiting was related to their academic study area, and 13% reported that their interactions with the career center when in college informed their choice to enter the profession. College members were more likely to report these reasons compared to members in industry. (See Figure 2.)

Career Progression in Career Services and University Recruiting

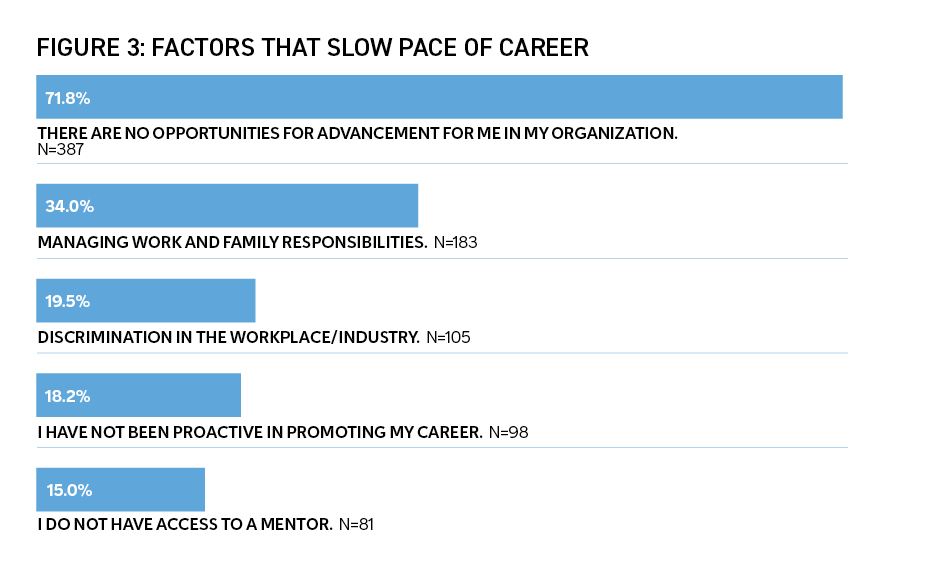

The ways professionals view the progression of their career in the field is mixed.

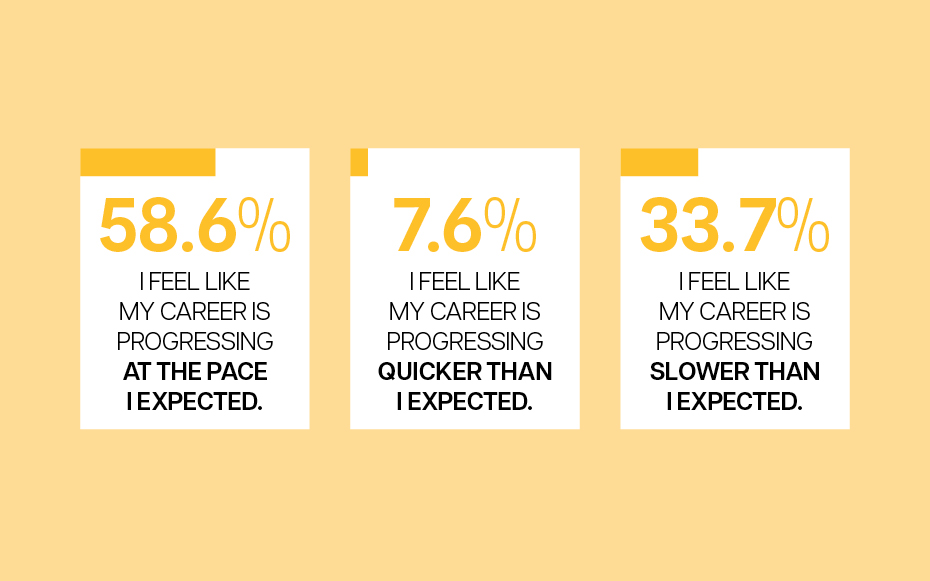

Overall, nearly six out of 10 respondents felt their career is progressing at a pace they expected, but more than one-third say the progression is slower than they anticipated. Among respondents, a lack of advancement opportunities in their organization is the single biggest obstacle to career progress. (See Figure 3.)

Slower-than-expected progress was more prominent among career services respondents (35%) than recruiting professionals (28%).

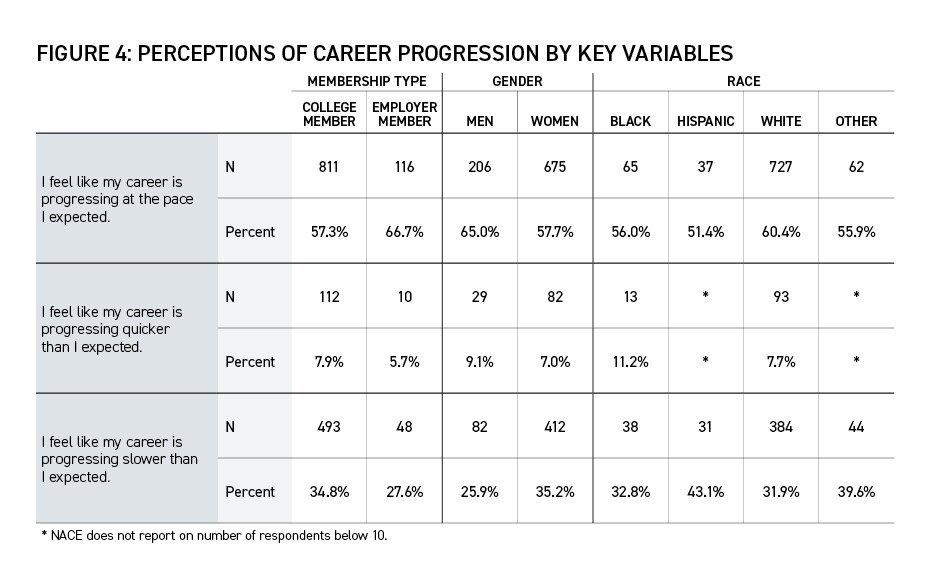

Gender and race also appear to be factors in career progression. Overall, men (65%) were more likely than women (58%) to report that their career was progressing at a rate faster than expected. By race, white members (60%) were more likely to report faster-than-expected progress compared to Black (56%) or Hispanic (51%) members. In addition, members who identify as Hispanic accounted for a greater share of those reporting slow progress than other categories. (See Figure 4.)

Career Services, Career Progress, and Implicit Bias

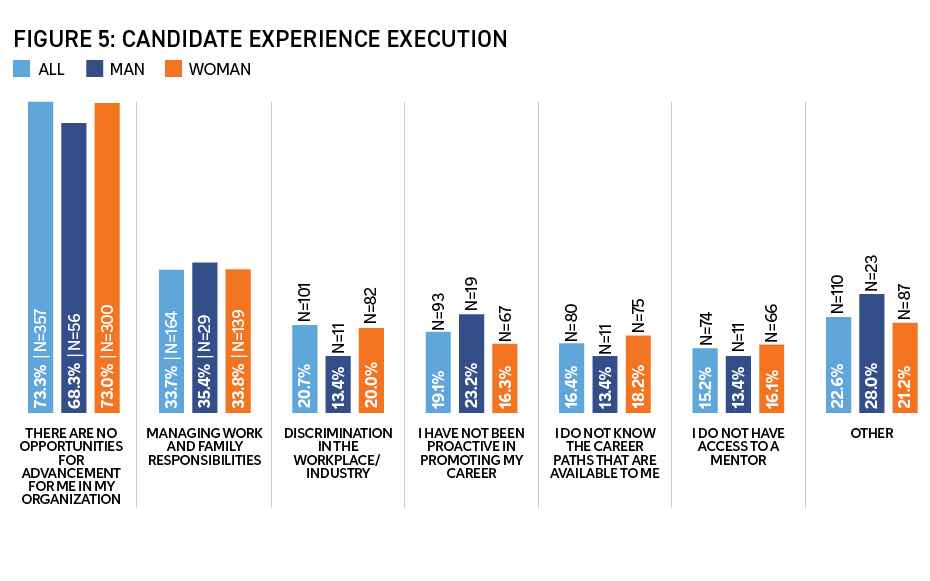

Among career services respondents who reported disappointment with the pace of their progress, the reasons beyond lack of opportunity were quite telling.

Overall, more than one-fifth of career services respondents reported that discrimination in the workplace impacted their progression, but that was skewed toward female respondents—21% cited discrimination as a factor compared to 13% of their male career services colleagues. (See Figure 5. Note: Due to the limited number of responses, race/ethnic data are not provided.)

This finding, coupled with the overall racial and gender differences in perceptions of career progression as illustrated in Figure 4, suggests implicit bias in the career pipeline that impacts progression. Interestingly, a slightly larger percentage of men (23%) than women (16%) reported that they were not proactive in promoting their career, thereby slowing the process. While this difference is small, it does lend some support to counter gender stereotypes that women are less inclined than men to self-promote.

Interestingly, a slightly larger percentage of men (23%) than women (16%) reported that they were not proactive in promoting their career, thereby slowing the process. While this difference is small, it does lend some support to counter gender stereotypes that women are less inclined than men to self-promote.

Social Capital and Career Progression

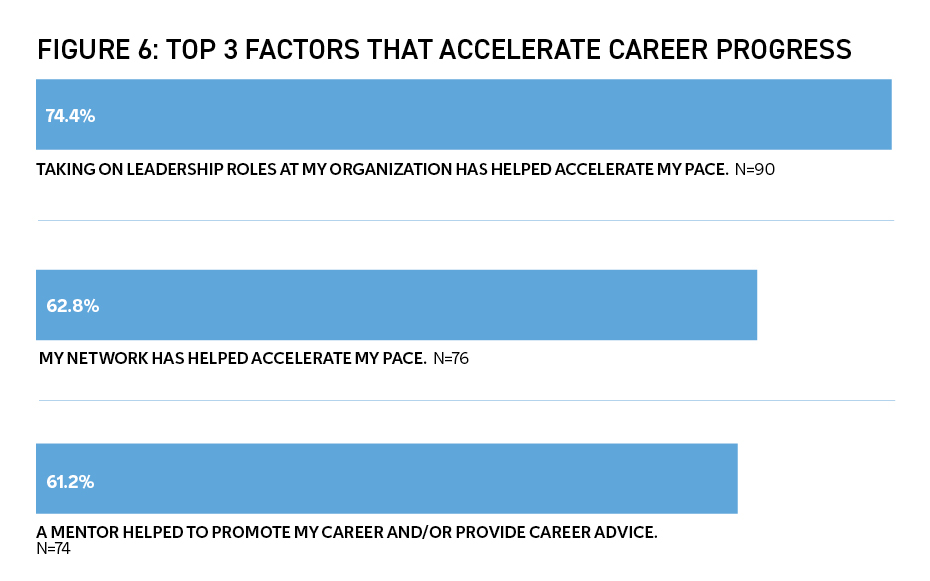

A lack of opportunities is a huge barrier to advancement for many, but when advancement is possible, social capital plays a significant role.

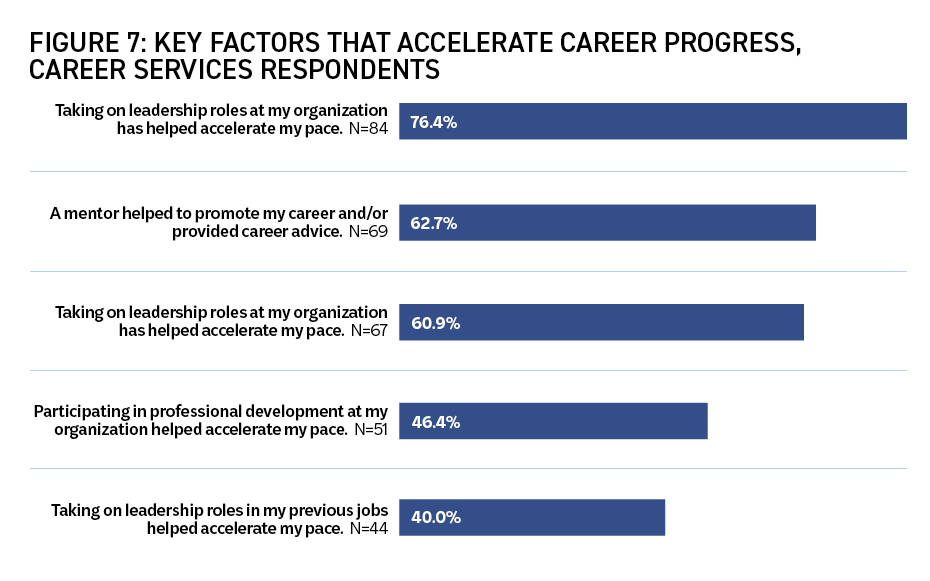

This is especially evident among those reporting faster-than-expected advancement: Although just a handful reported an accelerated pace, more than 60% of those who did pointed to social capital resources—having help from their network and engaging with a mentor—as contributing to their advancement. Moreover, it is likely that the biggest factor cited as a career booster—taking on leadership roles within their organization—is fostered or made possible at least in some part by networks and mentors, i.e., social capital. (See Figure 6.)

This pattern repeats when we look at responses among career services professionals. (See Figure 7. Note: Due to the limited number of responses, employer data are not provided.)

The Role of Networks and Mentors

Given their importance, it is helpful to understand the role of networks and mentors in the profession.

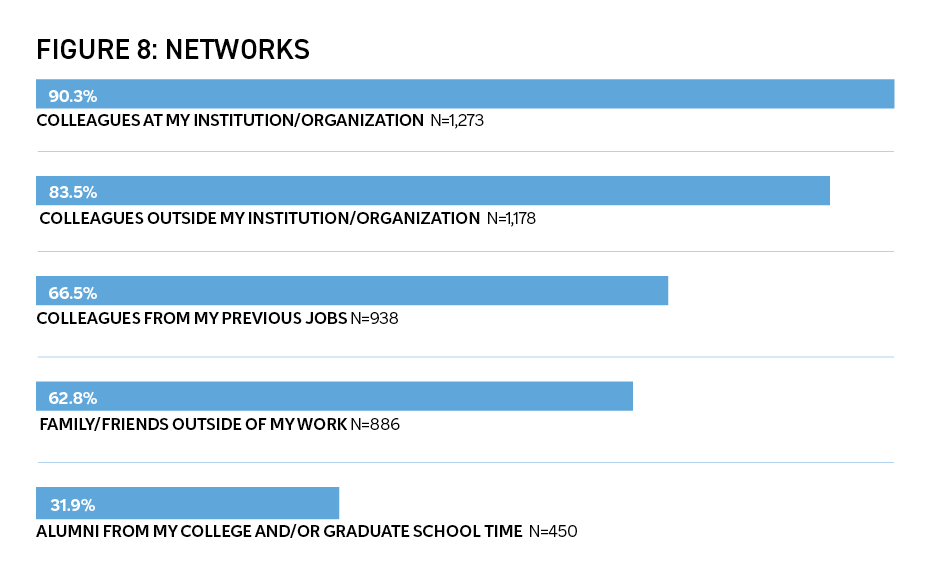

Overall, 90% of respondents reported that they have a network they can draw on for career advice and support. As Figure 8 shows, nine out of 10 count their current work colleagues as part of their network, and one-third include former work colleagues.

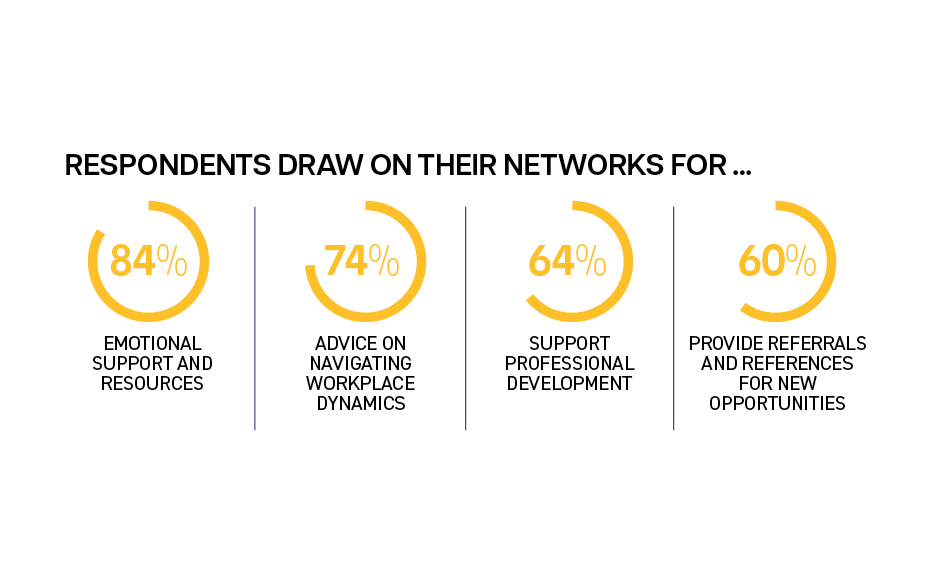

As noted above, networks are important to career advancement, but when asked about what they gain through their networks, the largest portion of respondents cited the emotional support, followed by helping navigate workplace dynamics.

Mentors, however, are nowhere near as prevalent. Only one-third of respondents said they currently have a career mentor they could turn to, and less than one-quarter (24%) said they had participated in a formal mentoring program in their workplace.

Interestingly, while there was very little difference in the percentage of members who reported having a career mentor by membership type (37% of employer members and 33% of college members), there was a large difference in those who had access to a formal mentoring program in their workplace. More than one-half of employer respondents (52%) said they had access to a formal mentoring program as compared to just 20% of college members. This points to the fact that within industry, formal mentoring programs are more common than in higher education.

There is not much difference between men (35%) and women (32%) in terms of having a mentor, but there are more pronounced differences by race/ethnicity. Black respondents (41%) were more likely to report engaging with a mentor than were their white (33%) and Hispanic (24%) colleagues.

Mentors play a key role in individuals’ careers. Among those who had mentors, 82% reported that mentors provide advice on navigating workplace dynamics in their current job, 80% reported that mentors provide emotional support and resources, 74% said mentors support their professional development, and 64% look to mentors to provide advice in planning their career progression.

Working Toward Promotion

Slightly more than one-half of respondents (51%) reported that they were working toward a promotion in the next two years. By variable, results show:

- Men were a bit more likely than women to report they were working toward a promotion (54% versus 50%).

- Professionals of color were more likely than their white colleagues to be working to advance: Sixty-five percent of Hispanic professionals and 60% of Black professionals reported that they were working toward a promotion compared with 48% of their white colleagues.

- Recruiting professionals (70%) far outpaced their career services counterparts (49%) in terms of working toward a promotion.

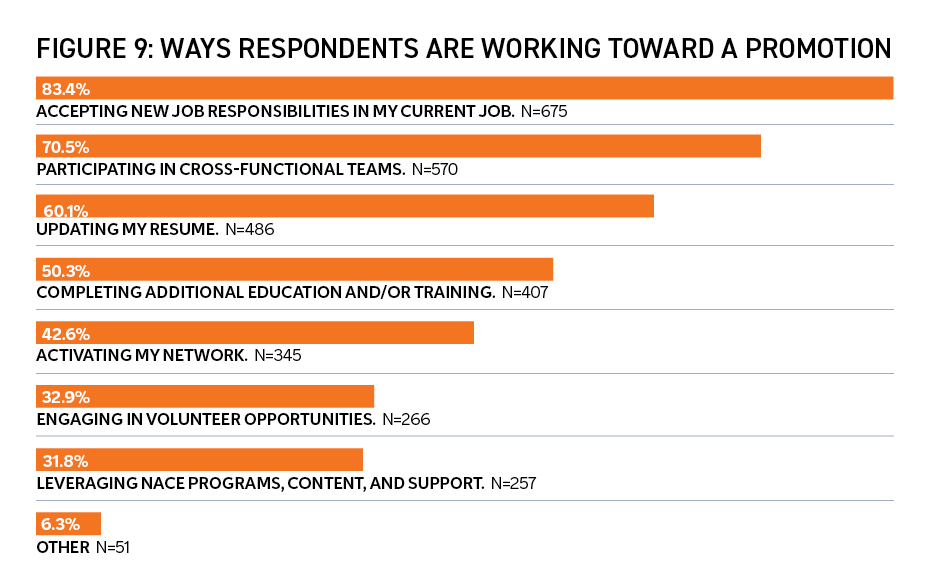

Those striving for promotion most frequently cited taking on new job responsibilities in their current job as a means to gaining a promotion—showing rather than telling leadership that they are capable of more. (See Figure 9.) Interestingly, more than 70% also indicated they were taking part in cross-functional teams as part of their effort; this ties back to the role networks play in career advancement and shows that those working to achieve a promotion recognize the value of expanding their professional networks.

Among those who are not working toward a promotion, a major reason was they were content in their current position (45%) had just been promoted (30%), or were nearing retirement (24%). However, one-third of respondents reported that they weren’t working toward promotion because there were no promotion opportunities available at their organization; 28% noted that they would have to leave their organization to have a promotion. The lack of advancement opportunities within one’s organization, and the subsequent need to change employers, serve as a barrier toward forward progression in the field.

Key Takeaways on Career Progression

NACE’s Career Progression in Career Services and University Recruiting Quick Poll offers a snapshot of how professionals view their careers and is a first step to understanding career progression among career services and university recruiting professionals. The poll offers some interesting insights into issues affecting careers in the field.

1. The majority of participants entered career services or university recruiting to help others in their career path, but fully one-third have found that their own career progression has been slower than they would have expected.

2. Limited advancement opportunities within their existing organization appears to be the largest factor in stagnant careers, suggesting that, for many, moving to another organization is the best—and possibly only—path to advancement.

3. Systemic forms of discrimination are thwarting career progress for many: Nearly 20% of respondents overall cited discrimination as a factor in their slower-than-expected career progress.

4. Taking on leadership roles and gaining guidance and support from networks and mentors are effective means for propelling a career forward. However, access to mentors and formal mentoring programs appears to be limited, particularly in higher education.