NACE Journal / August 2022

As a career coach, I meet with both domestic and international students who are hoping to build their connections in a variety of industries. Many of our newer graduate programs in the Katz School of Science and Health can be completed in as little as 12 months, so there is a relatively short runway for these students to develop and cultivate their industry connections. LinkedIn offers students and professionals easy access to the world’s largest professional network.

In considering how to encourage early adoption and increased used of LinkedIn among our students, I noted that companies frequently employ gamification and incentives to encourage engagement and certain behaviors. In fall 2019, I launched a competition among students in our graduate courses that was designed to foster a habit of regular and frequent engagement with LinkedIn—the Katz LinkedIn Challenge. Below is an outline of these efforts and the results.

Developing the Katz LinkedIn Challenge

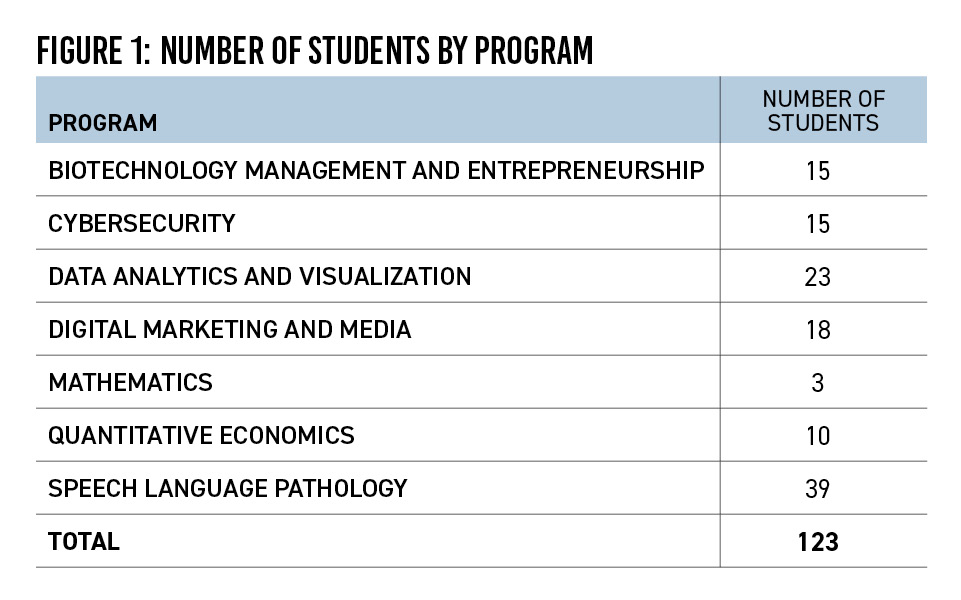

Our relatively new graduate programs provided an ideal sample to initiate the Katz LinkedIn Challenge (KLC), with programs ranging from three to 30 students. (See Figure 1.) I chose to use the number of LinkedIn connections as our key metric because it is the most convenient and available metric to monitor, measure, and reward. A two-month challenge period was selected for a variety of reasons including:

- According to a 2009 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, on average, it takes an average of 66 days for a new behavior to become automatic.1 (Full disclosure: The range is 18 to 254 days depending on the habit.)

- The time frame allows time to track and reward students’ progress at bimonthly intervals and gives staff adequate time to offer tips and support along the way.

- It would enable me to have sustained contact with students through the end of the calendar year and an opportunity to review, tailor, and potentially recalibrate our center’s outreach to the students during the spring semester.

KLC Timeline

August 2019: At orientation, encouraged School of Science and Health graduate students to adopt/leverage LinkedIn as a key networking tool.September 2019: Began promoting the challenge via classroom visits, email, and newsletter.

October 2019: Ran LinkedIn headshot clinics.

November and December 2019: Established baseline, launched the competition, tracked student progress at bimonthly intervals, and communicated ongoing results with leaderboards and “milestone winners.”

January 2020: Announced results, awarded final prizes, and identified and initiated follow-up and outreach.

Promoting the Challenge

During September 2019 orientation for all new students, I introduced our center’s primary offerings and highlighted success stories from alumni who used LinkedIn to grow their professional network and opportunities. I closed by inviting attendees to take out their phones and download the LinkedIn app, announcing that I would be visiting each program within the next month to provide tips on expanding their network and that I would share more details about the KLC to be launched that November.

I had arranged with each program director to take 15 to 30 minutes of regularly scheduled class time during the third or fourth week of the semester. This would give students adequate time to settle into their new routines as graduate students before my class appearances. During these class visits, I recapped some of my orientation presentation and asked the students to take out their phones and enable LinkedIn’s proximity feature to see who else in the room they had not yet connected with. Following this quick “game,” I promoted the upcoming challenge and encouraged the students to take part in the free LinkedIn headshot clinics offered by our career center. I also encouraged students to use our one-on-one coaching opportunities or to come by during my weekly drop-in hour to talk about their career strategy.

At around this time, we launched a bimonthly newsletter, in which I highlighted the upcoming challenge. I used this in addition to mass emails to communicate with students both prior to and during the challenge.

On November 1, the KLC’s launch day, we established a baseline for the challenge by recording the number of connections for all 123 incoming students in the School of Science and Health.

Results and Initial Findings

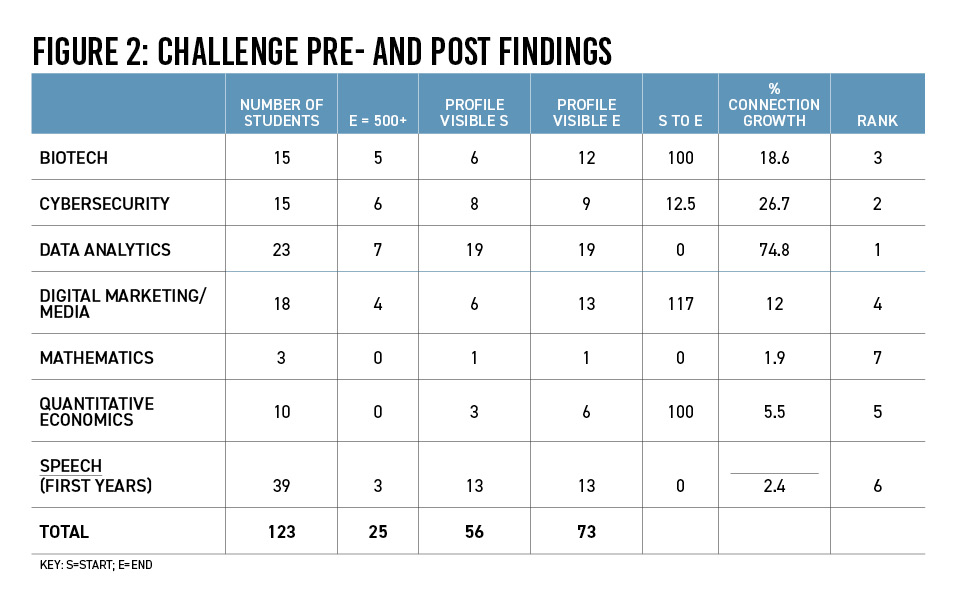

Prior to launching the challenge, we identified the number of connections each student had at the start of the challenge; at this point, more than 50% of our students did not have a profile that was easily discoverable (“visible”) on LinkedIn. (See Figure 2.) This prompted me to add a tip in one of my email updates and emphasize in individual coaching the need to personalize your LinkedIn URL, fully build out the profile, and make sure the headshot was unrestricted, i.e., visible to everyone.

By the end of the challenge, the profiles of 73 of our students—just shy of 60% of the total—were easily discoverable; although that is far from perfect, it is a 28% increase from the start. Although the number of participants from the biotech and quantitative economics programs was small, twice as many students in both programs had a visible profile at the end of the competition, which was encouraging.

By the end of our study, 11 students had achieved a milestone of 100, 200, 300, 400, or 500 connections. Each was profiled in one of our bimonthly email updates and/or in our center’s newsletter together with a quote or tip from them that related to the competition or to networking in general. Each received a $10 electronic gift card to Dunkin Donuts.

Three students achieved LinkedIn’s “magic” 500 connections by the end of the KLC. This meant that, four months into their program, there were now 25 students with 500+ connections, representing slightly more than 20% of the entire cohort. In addition to the gift card, I arranged with their professor to do a micro “award ceremony,” a two-minute in-person class presentation, in which each one was awarded an elegant keychain featuring the university’s logo. I hoped that profiling these students would encourage peer-to-peer conversations and sharing of tips on growing professional networks.

Overall, with a 75% increase in the number of aggregate connections in two months, the students in our data analytics program scored the highest. I scheduled a visit to their class and gave each student a thumb drive with our center’s logo on it.

On the other end of the spectrum, with less than a 2.5% growth rate, were our largest and smallest programs--speech language and mathematics. One possibility is that students in these programs were less eager to engage in the concept and process of networking. Our speech students were just a few months into a 24-month program and may have believed that clinical externships (of which they are guaranteed an interview with at least one organization) are a major factor in career paths, rather than networking. Challenging this explanation, however, are the data from our LinkedIn headshot clinics showing that the largest percentage of students attending were from our speech program. With just three students, our mathematics program is small: These students may bypass LinkedIn and instead rely on their professors to make introductions to industry professionals.

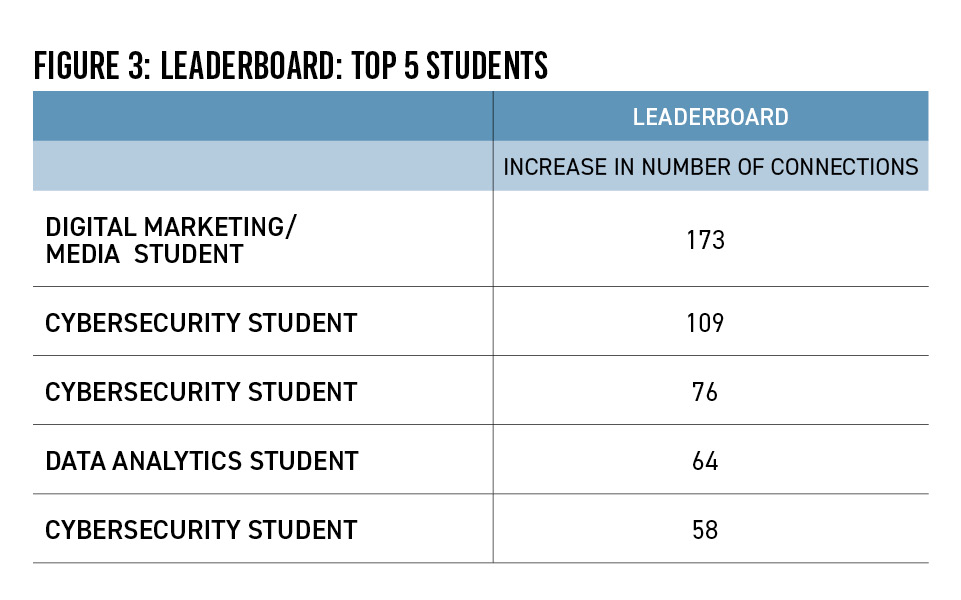

Not surprisingly, given the nature of their course of study, top performers were from the digital marketing and media program—with an increase of 173 connections over two months, an average of nearly three new connections per day—as well as data analytics and cybersecurity. (See Figure 3.)

Of course, there a significant flaw in this exercise: Using the LinkedIn metric alone does not provide a way to gauge the quality of a students’ connections. In fact, several students raised this issue both in my classroom visits and during 1:1 coaching sessions, enabling ample opportunity to emphasize the importance of quality outreach and connections, something that we reinforce through our center’s periodic workshops.

Also, regardless of whether an individual reaches 500, and regardless of the strength of those 500 connections (however that may be defined), it is always beneficial to keep growing, cultivating, and strengthening your professional network. The KLC was designed as a first step—a fun catalyst to encourage students to pay regular attention to LinkedIn.

Another important discussion that emerged with students during the challenge was the competition among peers—and the fact that competing against each other is OK. The competitive aspect simulates the “real world” where—especially as a student in a new specialized cutting-edge graduate degree program—the student may be competing with their peers for the same positions. An important byproduct of the challenge was the realization for some that they need to find a unique edge to differentiate themselves from their peers with similar backgrounds, and that one way to promote themselves (and achieve promotions in the workplace) is through the strength and value of their networks.

For Further Investigation

We found that approximately 80% of the students had not reached 500 connections by the end of the challenge. This gave rise to questions about the cohort. More than 40% of our graduate students are from overseas, and many have not have encountered LinkedIn before the challenge; this may contribute to a longer (and flatter) learning curve. This warrants further study to determine if different strategies and motivators may be needed for international students.

Similarly, because the challenge included only graduate students, how such a challenge would affect behavior among undergraduate students is an unknown. I hypothesize that a graduate population is more motivated to grow their network than their undergraduate counterparts, but without a much larger sample size for both populations, it would be hard to put this to the test.

We also do not know what, if any, bearing our interventions had on the results. A multisite study with a control group that receives no interventions, and/or different interventions, could tell us more about their relative effectiveness. When I next run the challenge, I plan to consider the correlation between student success on LinkedIn and the number of interactions with the career center, especially 1:1 coaching. Also, a larger and longer study could look at the average length of time it takes students to go from 0 to 500 connections and the factors that affect the outcome. Interviewing the “top performers” could provide useful insights and spur new programming.

I would also finetune the challenge by:

- Creating specific targets and milestones, e.g., everyone in a specific program reaching 250 connections within one month, or 90% of students having a personalized URL for their profile and completing at least seven of the steps highlighted on LinkedIn’s guide for college students, including a photo.

- Building in outreach to students who are straggling. For example, a message could target students who are yet to achieve certain milestones by midpoint of the challenge.

- Developing a peer-to-peer mentoring process. A peer or “buddy” system could pair those on the leaderboard with one or two students who were trailing.

- Repeating the challenge throughout the year as a means to enhance each student’s profile visibility, with an initial challenge in November and December, another in February and March, and then a final in June and July. As part of this, we could identify stretch goals, e.g., increasing visibility by 30% during each period (based on this study’s data set where we achieved ~28%).

Implications for Coaching Students

While a much larger longitudinal study would be needed along with a definition of student success to draw definitive conclusions about the relationship between LinkedIn adoption and success, the findings were very valuable on a micro level as a point of reference for coaching discussions during and beyond the challenge. For example, if I were meeting with a student who had an underdeveloped profile or was well behind their peers in network building, I could initiate a discussion around their future plans and timeline to inform and develop their career strategy.

If we believe that cultivating the habit of developing a professional presence and network on LinkedIn is a valuable professional skill, we need to devise and implement a strategy to help students achieve these. Our resources are finite, but simply providing a handout or tips is unlikely to inculcate a lifelong habit.

Rather than just a fraction of our students graduating with a well-developed LinkedIn profile and a strong network, consider what it would say about our career centers and institutions if the vast majority were easily “discoverable” and had a robust network.

Endnotes

1 Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C., Potts, H., & Wardle, J. (2010, October). How Habits Are Formed: Modelling Habit Formation in the Real World. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 6, 998-1009.