NACE Journal, February 2020

Buford and Nester also wrote on the undecided student in the May 2019 issue of the NACE Journal. See “The Plight of the Undecided Student”.

As institutions are asked to do more with fewer resources, career educators may be tempted to use similar approaches with different student populations. Although simpler in the short run, this tactic often fails to adequately support student growth and professional development in the long run. Isabel Myers-Briggs, one of the co-creators of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), once explained, “we cannot safely assume that other people’s minds work on the same principles as our own. All too often, others with whom we come in contact do not reason as we reason, or do not value the things we value, or are not interested in what interests us.”1 To approach all students in one linear way is a disservice to them, their learning styles, and the questions they pose.

In the fall 2018 to spring 2019 academic year, our research team partnered with the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Cincinnati to conduct semester-long professional development courses. In fall 2018, we examined the nature of first-year, undecided students’ beliefs about major and career through a three-credit-hour course.2 In spring 2019, we conducted a similar one-credit-hour course with first-year arts and sciences students who had successfully declared a major. Both courses aimed to prepare students to make thoughtful decisions about their time in college and post-graduate careers.

One year later, having closely examined more than 200 students, a number of insights emerged about the nature of undecided and declared students in the arts and sciences and what unique and distinct barriers they face in engaging with career education.

Undecided and Declared Students in the Study

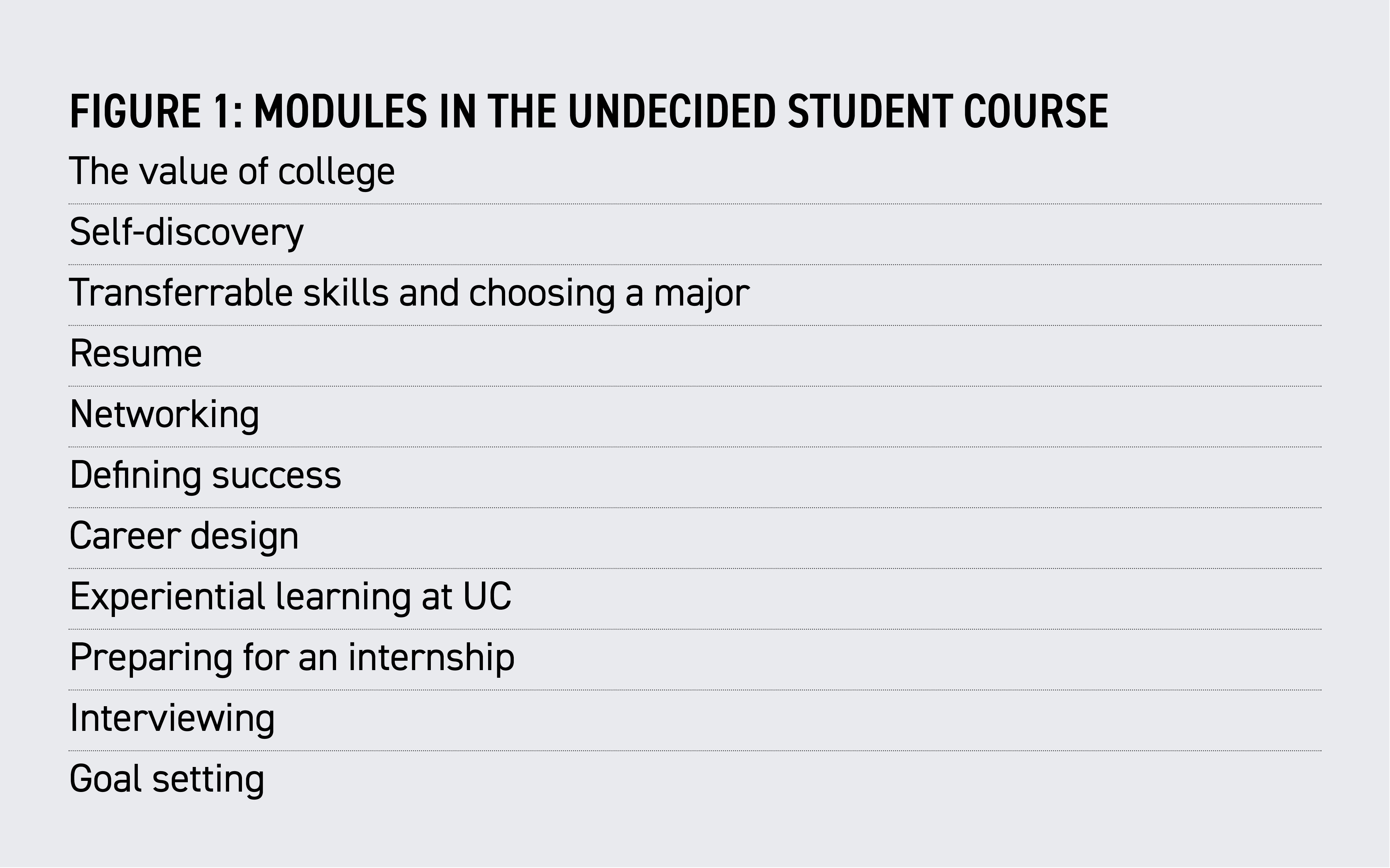

A total of 102 undecided students, approximately 95 percent of which were traditional college-age, first-year undergraduates, participated in a mandatory three-credit-hour pilot course. The course consisted of 11 modules, balancing self-awareness and career exploration. (See Figure 1.)

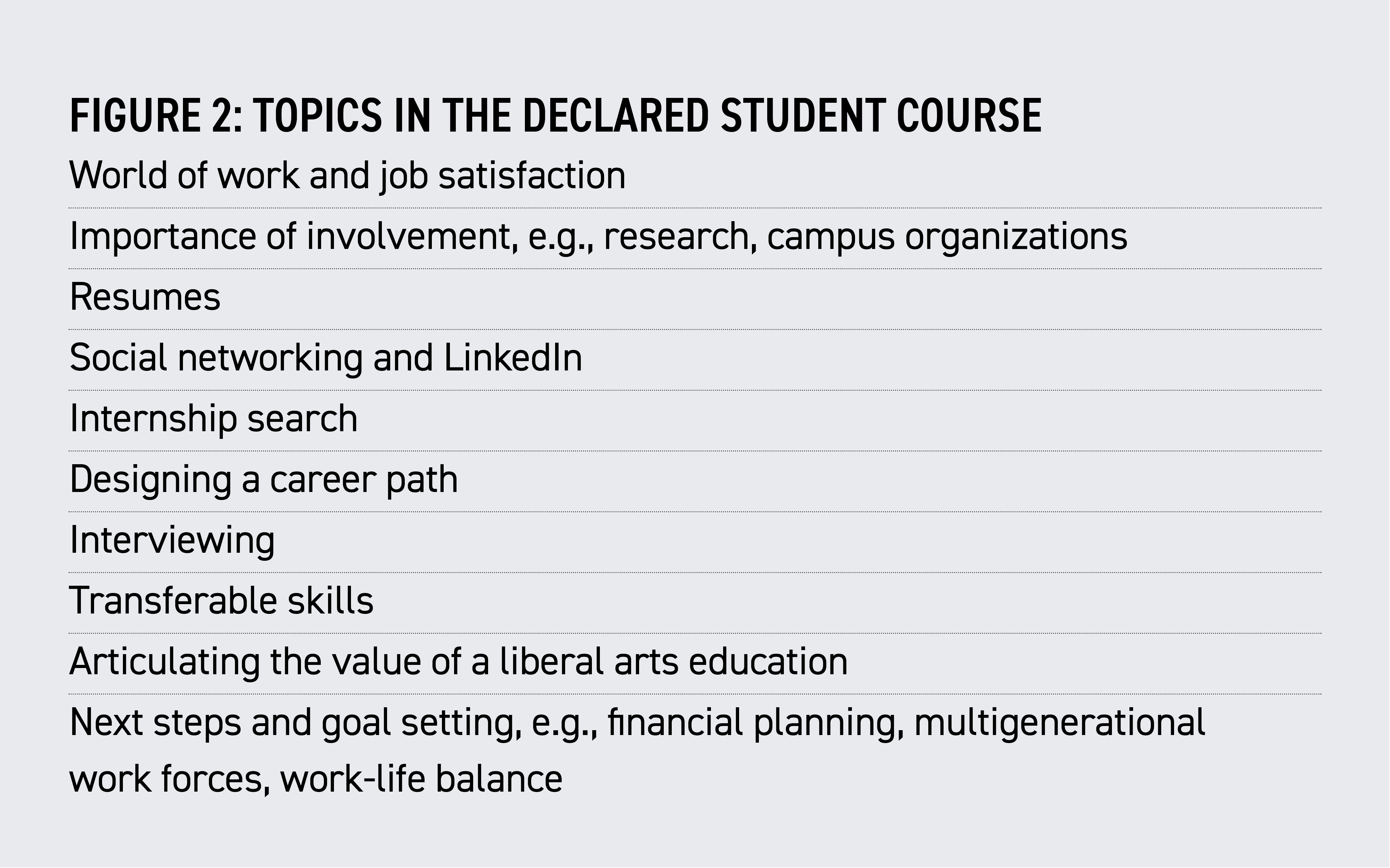

A total of 99 second-semester, first-year undergraduate students, with a wide range of declared majors in the arts and sciences, participated in a mandatory one-credit-hour pilot course. The course included various topics in the areas of self-exploration and career preparation, with a slight preference given to preparation. (See Figure 2.)

For both groups, we collected Myers-Briggs Types, top five CliftonStrengths, and students’ preferred career theorist among three distinct choices.

Comfort in Flexibility Versus Comfort in Structure

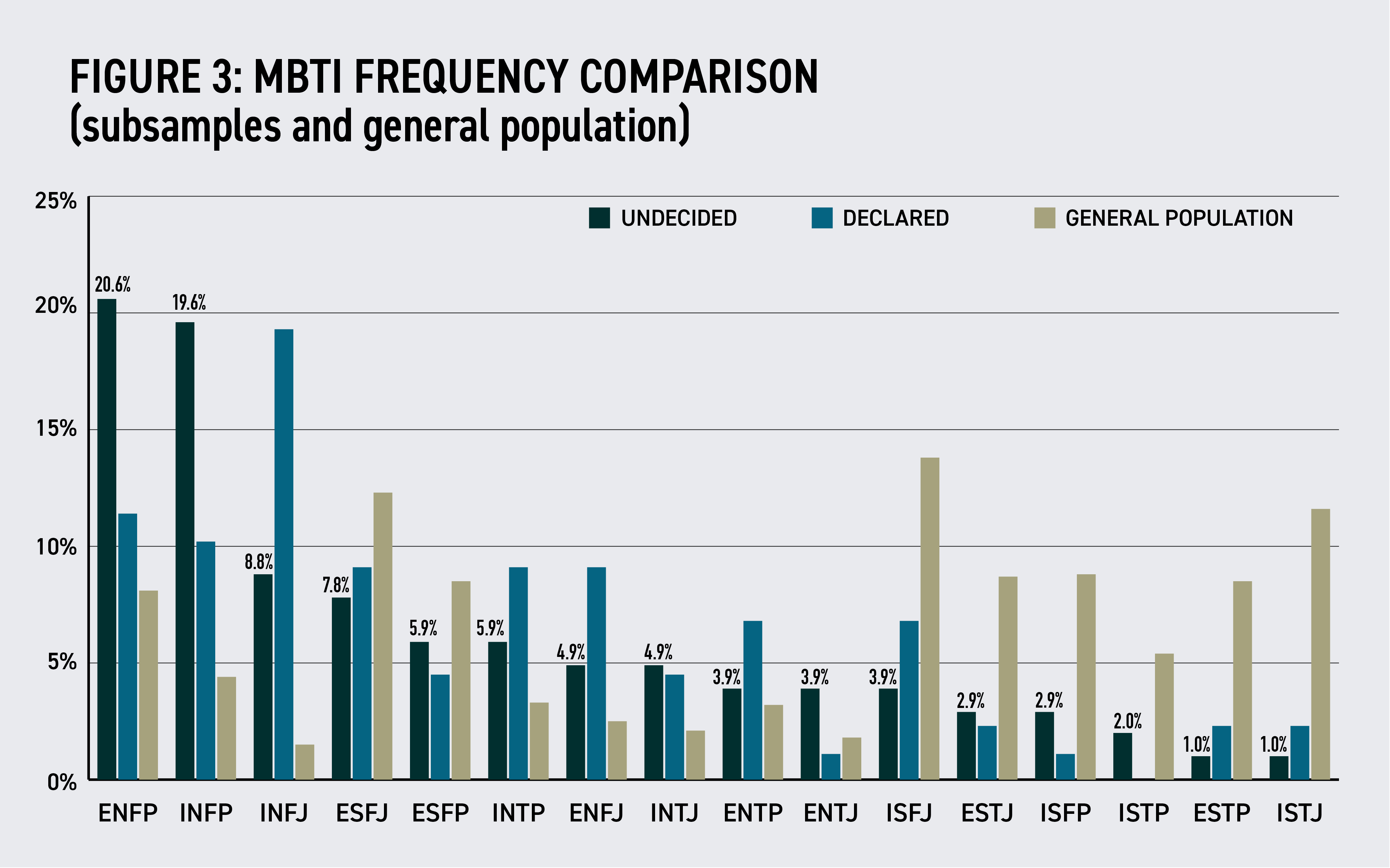

There were a number of similarities in Myers-Briggs Type results across the undecided and declared populations. Both groups demonstrated preferences for “feeling” and “intuition,” a combination associated with creativity, empathy, sensitivity, and big-picture thinking.3 Kiersey called these types “idealists,” notable for their pursuit of authentic and socially meaningful work.4 The split between introversion and extraversion was fairly balanced in both groups.

Undecided students find comfort in flexibility; declared students find comfort in structure.

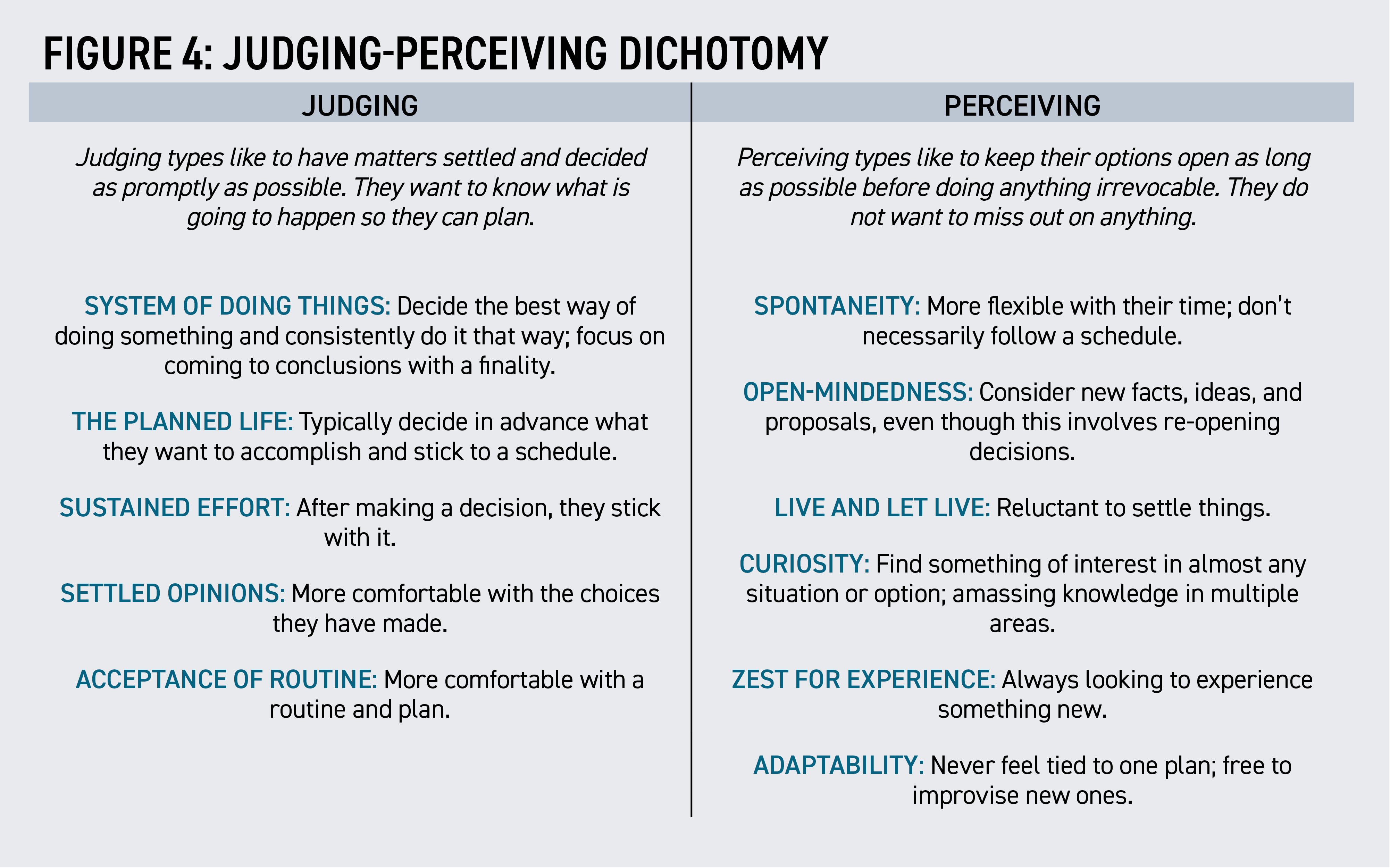

We finally start to see deviation in the fourth MBTI dichotomy, “perceiving” versus “judging.” Undecided students’ results suggested a preference for “perceiving” (62 percent to 28 percent).5 In contrast, a majority of the declared students demonstrated a preference for “judging” (57 percent to 43 percent).

Figure 3 compares the frequency of these two groups’ types with those found in the general population.

The difference in approach between these two preferences, especially how they organize and process information, highlights challenges and benefits to approaching career-related decisions. Figure 4 outlines some of the differences between the “judging” and “perceiving” dichotomy.

These results are consistent with what we might guess about undecided and declared students in the arts and sciences. Fleshing out differences inherent in “perceiving” and “judging” preferences gives us a sense of the needs, motivations, and limitations of these groups as a whole.

Declared students more commonly demonstrated a talent for planning and a relative comfort with structure. They were able to choose and apply for an academic program, and may have leaned on these strengths to do so. Conversely, undecided students were more likely to crave new experiences and the freedom to change their minds and develop new plans. A student who preferred “perceiving” would likely approach the process of major selection with different priorities than a student who preferred “judging.”

These data suggest that the approach to sharing professional development resources and career opportunities, and navigating exploration needs to be different for these two populations. Approaching each population—given their distinct priorities—with the same solutions may lead to frustration and distrust, and could potentially drive students away from services. One may be tempted, for example, to advocate for the importance of planning with an undecided student. This may be both well-intentioned and necessary, but this tactic would be more likely to succeed if it were accompanied by reassurance about opportunities to explore and change direction later on.

Declared or Not, First-Year Students Need to Explore Their “Why”

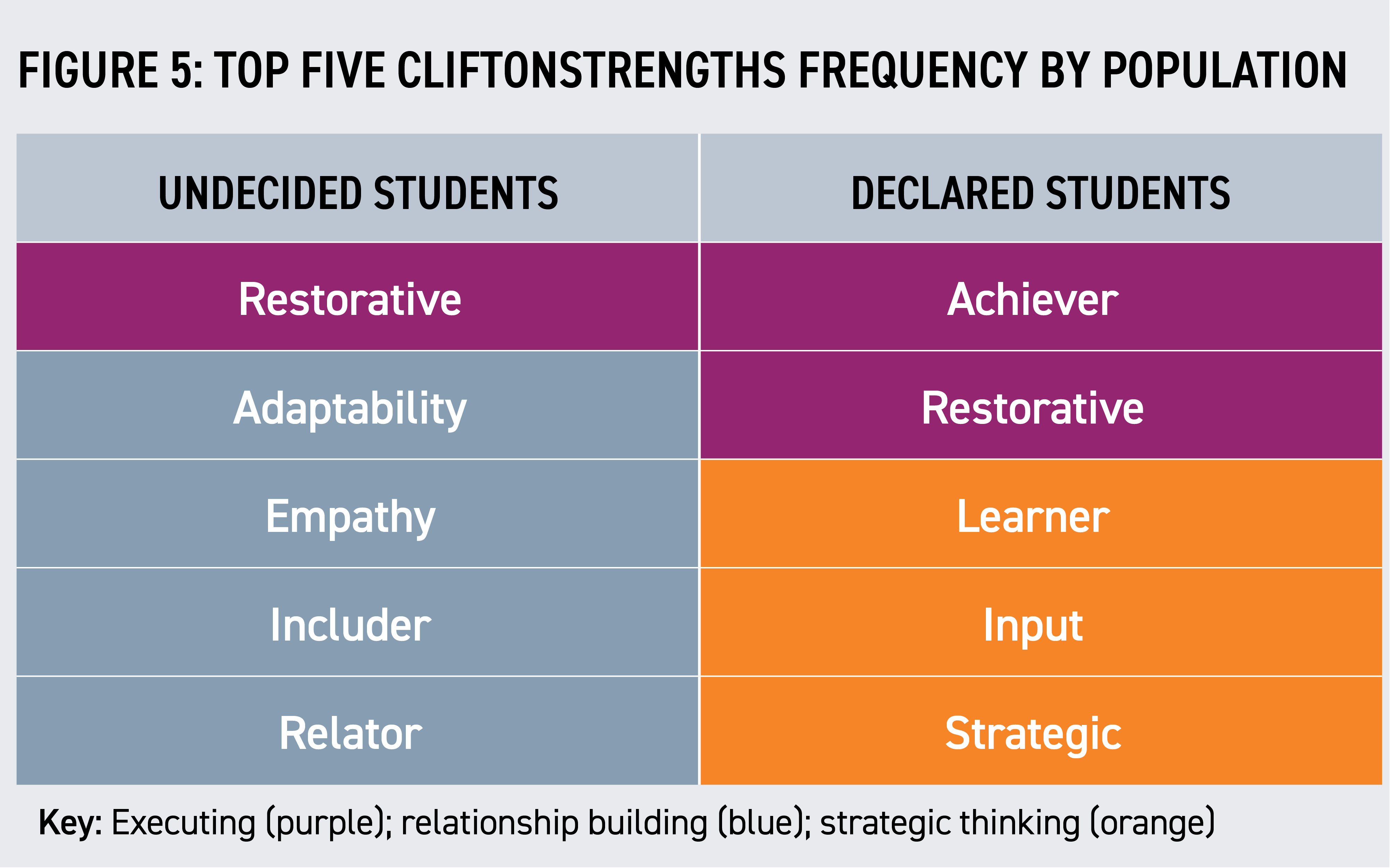

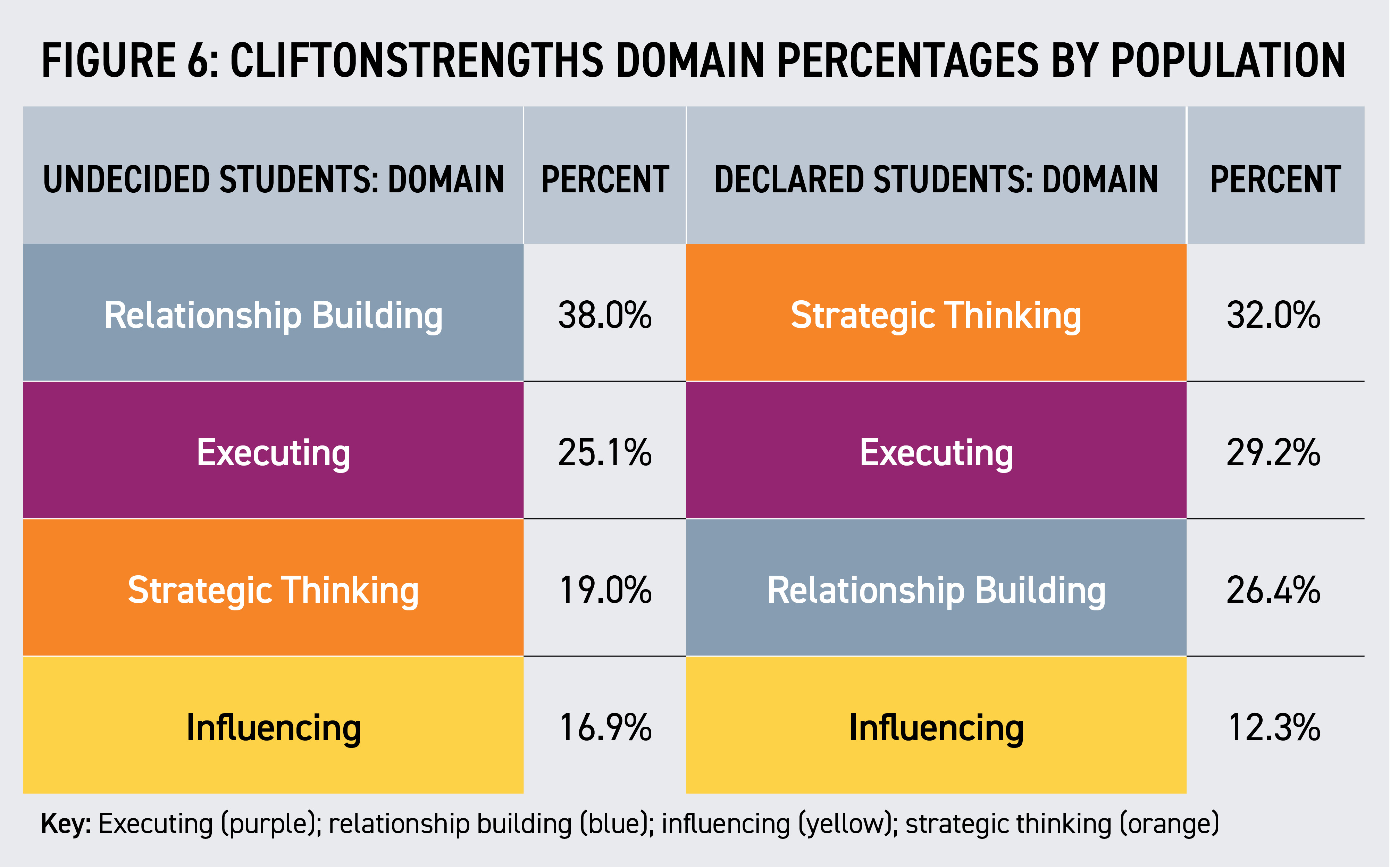

Students in both populations completed the CliftonStrengths assessment and shared their top five theme results. (See Figures 5 and 6.) Each of the 34 CliftonStrengths themes can be grouped into four domains: executing, relationship building, influencing, and strategic thinking.6

“Restorative,” the leading strength for undecided students, focuses on identifying and solving problems in a range of situations. According to the feedback from our teaching team, many students were quick to identify and voice potential problems with their career paths. With four of the students’ most frequent themes falling into the relationship-building domain, it is also noteworthy that many of their professional and career influences come from their peers and family. These students often reported investigating the careers of people they knew, which led to wrestling with whether these careers would fit them. Cycling through these options, unable to close out possibilities, became something of a trap for them. We found that these students first needed assistance to break this loop, and then support to focus on their values rather than the values of their peers.

Uniquely relationship-focused, undecided students may need to identify the “why” of what motivates them personally. Instead of relying on what those around them think, or falling into a “group-think” mentality, they would likely benefit from reflecting on why they have passions and drives in certain areas more than others. They need to differentiate themselves from others before they can formulate a plan.

In contrast, declared students’ top five strengths were principally located in the strategic thinking and executing domains. These strengths focused on taking action, solving a problem, learning and gathering data, and putting together a plan. The declared students, as evidenced by their ability to choose a major, were able to formulate a plan and stick with it through their second semester.

Declared students may benefit from pausing to reflect on the academic and professional decisions they have already made. They might explore such questions as “Why have I selected this major?,” “Why does this career path excite me?,” and “How can I use my strengths to succeed?” It should not be assumed that, because these students have declared a major, they have also appropriately reflected on their decisions and explored their “why.”

Students who foreclose early on career possibilities may also run the risk of operating with incomplete or inaccurate information. This may be especially true for students in the arts and sciences who have a wide selection of career options to contend with. Students may decide on one career option and begin moving into the executing phase before they have properly assessed the risks and feasibility of that option. This can be costly later if it results in an excessive number of changes in major or unnecessary extra time in school.

Preferred Career Approach

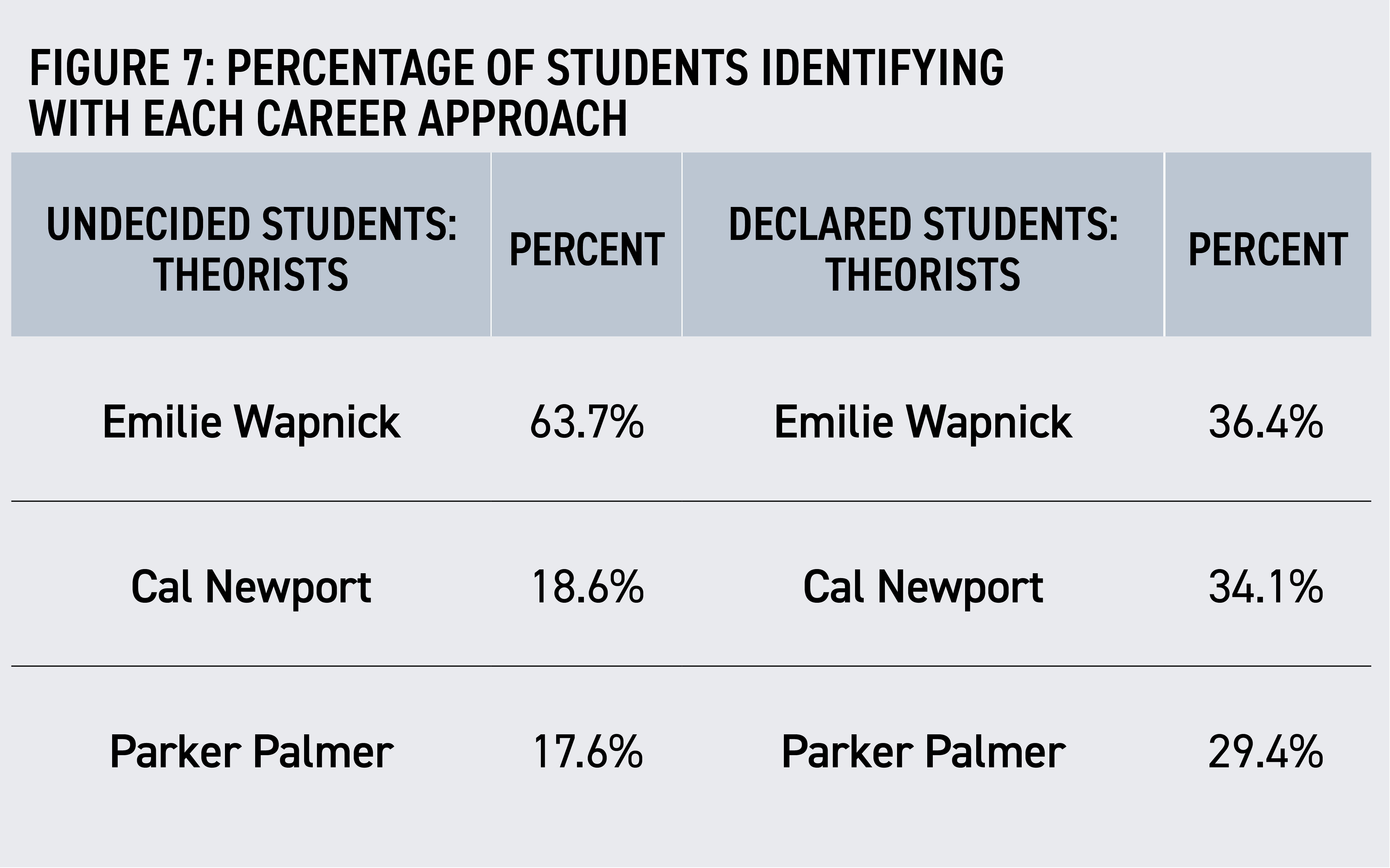

The third item we collected was students’ preferred career approach, represented by their choice of career theorist. Each student had the opportunity to choose one of three divergent authors of popular career guidebooks and write a reflective piece on why a particular approach captured his or her personal career philosophy. Students explored each of these thinkers through in-class lecture and personal investigation.

Undecided students embrace multipotentiality; declared students subscribe to varied career philosophies.

These included Emilie Wapnick, a millennial thought-leader who advocates for what she calls “multipotentiality,” the (sometimes simultaneous) pursuit of multiple interests or career paths; Cal Newport, who promotes the focused development of a “rare and valuable skill” that will allow professionals to maximize rewards and autonomy in a competitive global market; and Parker Palmer, a prolific educator, spiritual leader, and activist who explores the importance of following your authentic inner voice and finding a way to be of service to the world.7, 8, 9 Our research team selected these three figures to represent diverse approaches to career and definitions of success. In aligning themselves with one of these three experts, students were forced to consider the rewards and challenges of each approach.

As Figure 7 indicates, a clear majority of undecided students selected Emilie Wapnick (64 percent). Students embraced the idea of putting their multiple interests at the center of their academic and professional plans. They embraced her philosophy, regardless of their interests, potential career plans, or if they identified as multipotentialities themselves. Taking into consideration their MBTI preferences and top five CliftonStrengths, it makes sense that many undecided students felt validated by the acceptance-oriented stance of this approach.

In contrast, declared students had a closer split between the three approaches, regardless of major and interests. Declared students did not seem to clearly gravitate toward any one thinker. If anything, this underscores the inherent diversity of students in the arts and sciences. It is important not to assume declared students think alike as they look to their professional futures. Some want to pursue multiple paths, some want to specialize, and others want to find their authentic calling. Career education must speak to all three of these approaches or risk losing student engagement early on.

Our data reveal that both undecided and declared students thrive when their individual career needs are validated. For undecided students, it may be important to acknowledge the ways in which traditional models fail to fully capture their aspirations. For declared students, who tend to focus on a particular goal, it may be more impactful to acknowledge their goal (and the hard work they may have put into it) while simultaneously pushing them to interrogate the logic behind their choices.

Course Impact

In our final course evaluations, students shared which aspects of the course specifically supported their learning. Students spoke specifically to the value of a customized curriculum and to the wide variety of course topics.

Even in the course evaluations, we see that the items each population found beneficial were somewhat different. The undecided students focused on the benefits of exploring, understanding themselves, and clarifying their interests. The declared students focused on tangible outcomes of the course that fit into their strategic goals and next steps. It is worth noting that both groups appreciated the time spent on self-exploration.

Recommendations

Leverage what you know about each group’s strengths and limitations: Better understanding of the differences between undecided and declared students allows us, as career educators, to validate and uplift each group’s strengths, while strategically challenging them to balance their limitations. MBTI and CliftonStrengths are two useful tools for solving the problem of student engagement. Since we know that undecided students often have strengths representative of “NFP” types, we might look to this type’s foil for inspiration as we seek to teach and advise these students. The talents of an “STJ,” who we know are underrepresented in this group, may be the very capacities undecided students need to develop.

Since it is important to avoid stereotyping or oversimplifying student groups, openly sharing data points may promote engagement. Students often enjoy sharing their opinions. You might begin an advising session or a class by asking them to weigh in on relevant findings about their group, either data you have collected or wider research. For example, you might explain that some research suggests that undecided students tend to be interested in finding a creative career working with people, but often feel paralyzed by all of their options, and ask them to weigh in. This relatively low-stakes question can provide a foundation for a deeper conversation.

Validate declared students’ exploration of career niches: Declared students make significant gains by exploring their values, personalities, strengths, and possible career trajectories. Considering their dominant executing/strategic planning CliftonStrengths and a likely “J” preference on MBTI, these students are often looking to create a plan for moving forward. By encouraging them to explore the niches within their major, we validate their choice and allow them to dig deeper into their goals. Ultimately, they can choose a best-fit path and potentially evaluate whether their program aligns with their long-term career aspirations.

For example, students can use a “What Can I Do With This Major?” guide to research different areas/concentrations, employers, and strategies to succeed in their intended field. It places students in the driver’s seat of occupational research and lets them explore if their major is right for them.

Connect exploration with tangible outcomes for declared students: Declared students expressed a preference for exploration when they could tie tangible outcomes to the information. They did not want to explore aimlessly; instead, they wanted to know how they could move forward. Considering their dominant CliftonStrengths, focused in executing and strategic thinking, this emphasis on outcomes makes sense. Some ways you can connect exploration to career development include:

- MBTI: There are multiple ways to tie personality preferences into personal and professional development with declared students. You can use activities around conflict resolution that focus on group projects, the work force, or even roommate disagreements. Our students shared positive feedback about sharpening their awareness of self and others.

- CliftonStrengths: One of the easiest ways to connect CliftonStrengths to career development is teaching students how to explain their strengths during an interview. Create activities that allow students to describe their strengths in their own words, without using CliftonStrengths terminology. This gives them the opportunity to reflect on their strengths, claim them as their own, and learn how to positively sell their skills during an interview.

- Career theorist/approach: After students have connected to the theorist they identify with, they can begin to plan their next steps. Help them translate their career approach into a tangible “plan,” e.g., finding an internship, exploring additional career options, and so forth.

Encourage undecided students to explore multiple major and career options—and set a deadline: Since undecided students so often value exploration and complexity, they will likely be best supported by an approach that honors multiple major and career possibilities. Design activities and assignments that allow for this, but also ultimately move students toward timely decisions and action planning. Providing an undecided student with a two-step process, first an opportunity to indulge in exploration, and then a deadline to move things forward, may prove most effective.

This mirrors feedback from the course evaluations. Undecided students expressed an appreciation for feeling “guided” through the process of major and career selection and preparation. The more sensitive and holistic the support we provide to these students, the better.

Engaging Undergraduates in Career Preparation

Our exploration of first-year undecided and declared students’ strengths and career identities revealed a number of challenging ideas. Both are complex and diverse groups with different approaches to career, necessitating that each population be approached in customized, informed ways.

Engaging students in career preparation at the undergraduate level is a near-universal challenge. Efforts to better understand the unique characteristics of different student populations will enhance our capacity to meet students where they are. By customizing our approaches to instruction, programing, and advising, we can ensure that students feel heard and engaged in the work of career development.

Endnotes

1 Briggs, I. “Isabel Briggs Myers: Biography, Test & Quotes.” Retrieved from study.com/academy/lesson/isabel-briggs-myers-biography-test-quotes.html.

2 Buford, M., & Nester, H. (May 2019). “The Plight of the Undecided Student,” NACE Journal. www.naceweb.org/career-development/special-populations/the-plight-of-the-undecided-student/.

3 Tieger, P. D., & Barron-Tieger, B. (2007). Do what you are: discover the perfect career for you through the secrets of personality type. 4th ed. New York: Little, Brown and Co.

4 The Kiersey Group. “Portrait of an Idealist.” Retrieved from keirsey.com/temperament/idealist-overview/.

5 Percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

6 Pong, Kim, et al. (2019). “CliftonStrengths Theme Frequency All Countries 20 Million People (Strengthsfinder).” Retrieved from strengthsasia.com/cliftonstrengths-theme-frequency-all-countries-20-million-people-strengthsfinder/.

7 Wapnick, E. (2017). How to Be Everything: A Guide for Those Who (Still) Don’t Know What They Want to Be When They Grow Up. New York: HarperOne.

8 Newport, C. (2012). So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

9 Palmer, P. (2000). Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.