NACE Journal, August 2018

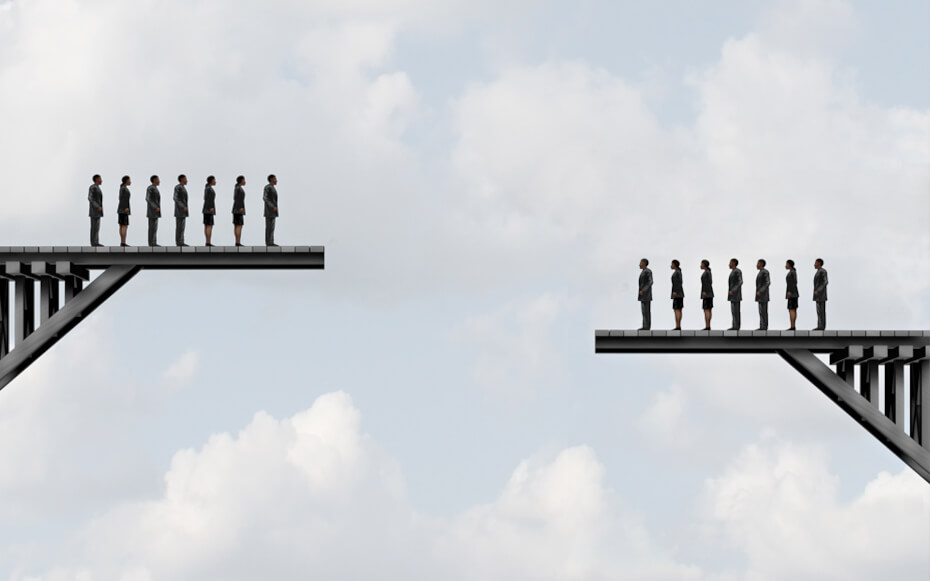

Imagine there is a large expansive waterway separating two islands. The inhabitants of both islands decide that a bridge is needed to connect their two lands, and each sets off independently to build one. Before too long, both notice the efforts of the other and decide to make their bridges connect. The problem is that both islands speak different languages and use different units of measurement; not surprisingly, when the bridges are complete, they fail to connect with each other. Neither has the resources to rebuild their side of the bridge, so when citizens from either land need to cross the bridge, there is only one solution—they must jump from one bridge to another.

It is not difficult to see parallels between this metaphor and the current condition of career preparation in the United States. Colleges and universities invest considerable financial and human resources in the development of their students’ career readiness. Business and industry also make a major investment in securing the work force they need to meet their goals. If we were to extend our metaphor a bit farther, we might hear business leaders complain, “Yes, it’s a great bridge, but it doesn’t go far enough.” They might also say, “We’ve told you many times where we need the bridge to be.” Their higher education counterparts might reply, “Look, bridges are considerable undertakings. It’s hard to change them quickly.” They might also add, “And, your bridge keeps moving! How can we connect to a bridge that won’t stay put?”

The challenges of career preparation and leadership development in the 21st century have many of the same complexities. Employers have communicated time and again that there is a gap between the readiness of new college graduates and the expectations of employers. That gap comes in the form of both technical skills (hard skills) and transferable skills (soft skills). In the past few years, colleges and universities have found ways of meeting these needs, but there is still much work to be done.

Adding complexity to this challenge is the fact that colleges and universities also have disconnected bridges—sometimes referred to as “silos”—on their own campuses, where many internal characteristics of the higher education environment inhibit collaboration. These include competition for resources within the institution, differing ideologies about the very nature of the work being done, and the impact of regulatory compliance, which has swelled workloads and which leaves insufficient time to truly collaborate. Seldom do complex problems have simple solutions, and the career preparation of contemporary college students is no exception. However, an area that has tremendous promise for addressing this issue lies within student leadership development through cocurricular experiences.

In this article, we advance a new leadership model to connect the very different worlds of higher education and business and industry: the Cocurricular Career Connections (C3) Leadership Model. This model also has the potential to create integration between students’ experiences inside and outside of the classroom. It can be used as the basis of structured leadership programs, and can also be used by business leaders to create professional development programs that connect to the training individuals received in college.

The Model

There are many useful leadership models and frameworks to guide leadership educators in creating programs, and to help individuals understand how to approach their own leadership development. Yet, many leadership programs on college campuses still struggle with recurring issues that limit the impact of these programs. One study found that, “Despite the illusion that most universities now have sophisticated collegiate leadership development programs, many campuses identify themselves as at early stages of building critical mass...or working to enhance quality....”1 They also suffer from the same issue identified at the beginning of this article: a failure to connect. The same study noted that these programs “are not collaborating with important stakeholders and instead operate as siloed programs.”2

The C3 model offers a structure for bridging and integrating a variety of experiences on and off campus, including 1) connecting cocurricular learning to classroom learning, 2) connecting experiential learning to learning in structured leadership development programs, and 3) connecting learning in college to learning throughout one’s career.

Connecting cocurricular learning to classroom learning:There is no agreed upon definition of the term “cocurricular experience.” If you ask a variety of professionals in higher education, you will get a variety of answers. This is especially true if you ask both faculty and student affairs practitioners. The conventional wisdom often asserts that “cocurricular” is simply a more contemporary term for the outdated “extracurricular.” Some might say that the “extra” in extracurricular downgrades the importance of these experiences, suggesting that they are nice to have, but not essential. These points are valid, but this work is grounded in the belief that the terms “extracurricular” and “cocurricular” are both needed to convey the potential of experiential learning. We therefore offer the following definitions:

- Cocurricular: Experiential learning opportunities that contribute to gaining skills and abilities that are part of the core competencies, and/or outcomes established by the institution and its governing bodies.

- Extracurricular: Experiences that provide the opportunity to engage with the institution and that connect students to others within the community in meaningful ways.

Essentially, cocurricular experiences are based on learning that is planned and which is expressed in learning outcomes. Extracurricular experiences may teach students something, but their primary role is to foster a sense of engagement and connection.

Many student affairs practitioners have struggled with their role as educators, particularly with the question of how their programs advance teaching and learning at the institution. If you ask a group this question, the response will often be a variation of “We give students the opportunity to apply skills they are gaining in the classroom.” This is a lofty aim, but it often falls short.

This topic was addressed by former NASPA Executive Director Gwendolyn Dungy, who wrote, "It's time to stop saying that our programs complement the teaching and learning that occurs in the classroom, when at too many campuses student affairs has no relationship with the faculty and no idea about what the student's experience is in the classroom."3 Perhaps that is true, but how would student affairs practitioners even approach this? How can a chemistry major, for example, apply the technical skills they gain to their work in a student organization? Certainly, there are some experiences that might provide this opportunity, but these could be very limited. Even a student majoring in accounting, who has skills that could be very useful to a variety of cocurricular programs, will find that only a small number of students can serve as treasurer, for example, or have other similar experiences.

There has been mounting evidence of and growing acceptance for the connection between participation in cocurricular experiences and the development of skills desired by employers.

As higher education strives to connect students’ learning outside of the classroom with their learning in their academic programs, it is clear that this work has been inhibited by focusing too much on the production of technical skills. Since it would be impossible for all or most participants in a cocurricular activity to develop technical skills relevant to each of their specific majors, many abandon the premise altogether.

In recent years, there has been mounting evidence of and growing acceptance for the connection between participation in cocurricular experiences and the development of skills desired by employers. Griffin, Peck, and LaCount found that after classroom learning, “no other experience that we studied made as big of an impact on students’ perceived development of skills desired by employers as did participation in cocurricular activities.”4 Likewise, Peck, Hall, Cramp, Lawhead, Fehring, and Simpson wrote, “Considering non-classroom experiences, in six of the 11 skills investigated…cocurricular experiences were the most likely to be selected by students as significantly contributing to their knowledge of the skills employers desired.”5 The connection between transferable skills developed in a cocurricular context and the skills that employers want appears to be well-supported.

Perhaps a much simpler, more intuitive connection could be found by focusing leadership programs on transferable skills such as the career readiness competencies developed by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). The overwhelming majority of academic programs are designed to produce technical skills that can be useful in one’s career (though they also produce transferable skills). Designing cocurricular experiences to expose students to transferable skills that are useful in a wide variety of careers can provide a path to accomplishing the elusive goal of integrating student learning inside and outside of the classroom.

The NACE career readiness competencies provide the structure for the C3 model. These competencies are critical thinking/problem solving, oral/written communications, teamwork/collaboration, digital technology, leadership, professionalism/work ethic, career management, and global/intercultural fluency.

There is a clear connection between the skills identified by NACE and those already pursued in leadership programs. Research conducted by Seemiller catalogued 60 competencies of student leadership programs developed from an analysis of a vast array of sources from both curricular and cocurricular programs. In some form, all of the competencies overlap within the NACE competencies. Essentially, employability skills are leadership skills. The quantity and variety of skills identified by Seemiller adds credibility to the claim that leadership programs may not be sufficiently strategic in their outcomes. In addressing this, Seemiller recommends that, “Intentional leadership competency development stems from being mindful about competency selection, designing programs and curriculum around those selected competencies, and evaluating competency development and proficiency.”6 Focusing leadership programs on students’ career development is a very practical way to accomplish this goal.

The focus on leadership competencies within the C3 model should not imply that the practice of leadership should be reduced to the mere collection of skills. Leadership is more than just a position, and leadership development programs must focus on both individual skill development and promoting the ways in which teams create and sustain leadership in their groups and organizations. Day wrote, “In addition to building individual leaders by training a set of skills or abilities and assuming that leadership will result, a complementary perspective approaches leadership as a social process that engages everyone in the community .”7 Within our model, leaders begin by attending to their own skill development and then connect with other leaders to create and sustain leadership in their groups and organizations. This is discussed in more detail later.

By focusing on developing transferable skills in both cocurricular experiences and in leadership development programs, educators can integrate learning inside and outside of the classroom in ways they have not previously explored. The C3 model provides useful guidance in accomplishing this important goal.

Connecting experiential learning to structured leadership development programs:Yet another disconnect that is common in leadership development is a lack of connection between students’ experiences as leaders in cocurricular settings and the leadership training that is provided in structured leadership development programs. Students who participate in leadership training or who pursue academic coursework in leadership are not necessarily the same students who are practicing student leadership in student organizations and other cocurricular experiences. This has led many to develop different resources for these two groups. An important goal of the C3 model is to bring student leaders together with students studying leadership in classrooms and developmental programs.

Among the ways that the C3 model brings cocurricular leadership experience together with leadership education is through the focus on the application of skills. Without providing opportunities for students to apply what they learn, programs may fail to illustrate the greatest potential of leadership development to be applied by teams to accomplish their shared goals. Alexander and Helen Astin wrote, “The process of leadership cannot be described simply in terms of the behavior of an individual; rather, leadership involves collaborative relationships that lead to collective action grounded in the shared values of people who work together to effect positive change.”8 Providing students both leadership experiences and leadership training can be a powerful combination that can positively impact a student’s employability and success.

Connecting learning in college to learning throughout one’s career:Employers want more than just leadership skills; they want individuals with the mindsets that lead to growth in their career. In developing this model, we consulted with leaders in business and industry—especially those who focus on hiring new college graduates. When asked why her company prefers to hire graduates with student leadership experience, Amanda Robbins, vice president for talent acquisition at Mattress Firm, put it this way, “Engaged students become engaged employees.” She added, “They are eager, excited, and ambitious. It aligns with our core values.”9

Supporting the claim that student leaders are more likely to possess qualities that lead to their success is the work of Gallup, which has studied how a variety of experiences in college affects the happiness and well-being of students beyond their college years. Gallup’s research suggests that only 39 percent of college graduates are engaged at work.10 However, if graduates felt that their institution had prepared them for life outside of college, they were more than three times more likely to be engaged.11 This speaks to the role that engagement in college can play in preparing employees who have the energy and drive to be leaders.

Navigating one’s career is often a process of making meaning by looking backward rather than forward.

To provide a simple illustration of this concept, imagine two possible new hires. The first has a high level of technical competency, but a weak sense of engagement to the company. She is not self-motivated, does not work well with a team, and frequently applies for jobs at competing companies. Now imagine a second new employee. His skill level is lower, but he works hard to seek out additional training, embraces the culture of the company, and seeks to add value to each team that he is on. Most would agree that the second employee is the one they would rather have. A tremendous advantage of student leaders is that many have already demonstrated these qualities. They have demonstrated the leadership skills that have inspired their fellow students to put them in positions of authority and have sought out engagement with the institution in a meaningful way. In a way, hiring individuals with student leadership experience in college provides a way for employers to pre-screen their applicants to see who already possess the kind of motivation and engagement that puts candidates on the track to success.

Navigating one’s career is often a process of making meaning by looking backward rather than forward. In other words, it is often easier to understand the twists and turns a career has taken than it would be to understand or predict one’s career path from the beginning. Those of us who work with college students often have a ringside seat to the angst they feel as they attempt to leap from the bridge of college to the bridge of their career.

Much has been made of the struggles that the Millennial generation has had managing their careers. Stories abound of new employees frustrated with a lack of advancement at their companies within a very short period of time on the job, or students who apply for positions for which they are clearly unqualified early in their career. Career professionals often feel some culpability for the failures of these individuals, even though modern career centers often offer excellent resources to help students navigate the early stages of their careers. What is often lacking is a way for students to conceptualize all stages of their career.

The C3 model addresses this gap by embedding career planning into leadership training. While this is a relatively novel approach, the connection is quite intuitive. What is leadership development for? Certainly, leadership development should inspire participants to make a difference on their campuses and in their communities. However, leadership development is more than just leader development. It introduces individuals to the process of leadership, which involves leveraging the strengths of a group to meet shared goals. Regardless of industry, there will be opportunities to apply this knowledge in one’s career. If leadership development is limited to what students do during their time in college, institutions of higher education will be missing an opportunity to prepare students with skills that will differentiate them from other candidates during their job search, prepare them for success in their early employment experiences, and set them on a course for leadership across their career.

Finally, business and industry tends to view the professional development of their employees in terms of management training. This is different from focusing on leadership. Day explains this distinction, writing that management development programs often promote “the application of proven solutions to known problems.”12 In contrast, “leadership development refers to situations in which groups need to learn their way out of problems that could not have been predicted.”13

Differentiating management from leadership also underscores that distinction that leadership training must be more than simply skills-based and focused on the leader. Management training, according to Day, tends to focus on building “human capital,” which focused on “individual-based knowledge, skills, and abilities associated with formal leadership roles.”14 Leadership training focused on “social capital,” which involves, “building networked relationships among individuals that enhance cooperation and resource exchange in creating organizational value.”15 The C3 model provides a structure for business and industry leaders to develop their employees as leaders, increasing their effectiveness in working collaboratively to accomplish goals and solve problems.

Elements of the C3 Model

The C3 model is not intended to describe how students and employees experience their leadership and professional development. Instead, it is intended to provide a structure by which higher education and business and industry can develop leadership experiences that connect our two bridges.

It is also intended to provide an approach to ensuring that individuals will have the opportunity to gain higher-order thinking skills as they progress over time, and that what they learn will not only be philosophical in nature—they will need to develop their skills and the skills of their team as they progress.

Many leadership educators have struggled to look at how learning can be planned and evaluated as it occurs over time. It is the element of “time” that has proven most problematic. One student may be involved in a cocurricular experience for many years, but contribute and likewise gain very little. Another may become involved in an activity, immerse him- or herself in it, and derive significant benefit right away. Clearly, time is not the best framework for understanding the development of skills. In his development theory of student involvement, Alexander Astin articulated that “student involvement refers to the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience. Thus, a highly involved student is one who, for example, devotes considerable energy to studying, spends much time on campus, participates actively in student organizations, and interacts frequently with faculty members and other students.” 16

So, perhaps it is not time with which we should be concerned, but rather how much energy a student invests. The stages of the C3 model track the progression of students through this model based on the amount of personal investment and energy they devote to the activity. While the terms “involvement,” “engagement,” and “leadership” may most closely relate to cocurricular programs like student organizations, it is easy to see how this concept could also apply to other contexts like student employment.

Skill Development in the C3 Model

As individuals transition into their career, they must learn more than just job-search strategies.

As previously noted, the C3 model uses the NACE career readiness competencies as a structure for skill development. This is because each skill has a clear connection to leadership development and is valued by employers for career success.

As individuals progress in their cocurricular experiences, and as they progress in their careers, they are drawn toward deeper development of the skills. Though higher education has put increasing emphasis on teaching students to articulate the skills they are gaining that make them desirable to employers, these efforts often overlook that there is groundwork that must be laid in order for these efforts to be successful. Individuals cannot articulate skills of which they are not aware or that they have not yet acquired or applied. The progression of skill development is described through something we refer to as the 5 A’s: awareness, acquiring, applying, advancing, and articulating.

- Awareness of skill: The individual becomes aware of the skill and his/her level of competency in it.

- Acquiring skill: The individual establishes a baseline for competency in the skill.

- Applying skill: The individual puts this skill into practice.

- Advancing skill: The individual refines the skill, including teaching it to others.

- Articulating skill: The individual is able to explain the full spectrum of skill development related to this skill, including how the skills was acquired and how it has been applied and mastered.

Intellectual Development in the C3 Model

Intellectual development in college is naturally complex. In a curricular frame, classes naturally get more in-depth as students progress. While students certainly can gain more complex skills as they progress in their experiences outside of the classroom, there isn’t a parallel structure within the cocurriculum to ensure that this happens.

Higher-order thinking skills are necessary for the practice of leadership. Roberts wrote, “Deeper learning and deeper leadership are closely aligned, if not one and the same. As we look ever more closely at what we are achieving, there is emerging evidence that deeper learning is a necessary condition to foster deeper leadership.”17 A strong case can be made that this is currently a gap that leadership education is not filling. Owen wrote, “The world needs leaders who can synthesize knowledge across seemingly disparate fields and draw conclusions by combining examples, facts, and theories from more than one field of study.”18

One way that we can plan for incrementally complex learning is described in Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. 19 In 1956, Benjamin Bloom chaired a committee of educators to create a “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives,” which was intended to describe (among other things) how students developed higher-order thinking skills.20 The C3 leadership model crosswalks each stage of development with Bloom’s revised taxonomy of learning in order to help leadership educators and business and industry leaders plan increasingly complex learning at higher stages of leadership. These can be used to write learning outcomes for leadership programs and professional development or leadership training programs in business and industry.

Navigating the C3 Model

The model has eight stages. In total, they describe how college students can become involved in cocurricular experiences and how that involvement grows during their higher education career. The model presents a plan for incremental skill and intellectual involvement, and then helps students transition into their careers. It then describes how students transition their skills from college to career.

It is a significant challenge to create a model that is nested in skill development without limiting the usefulness of the model to the development of individuals as leaders rather than recognizing leadership as Komives defined it: “a relational and ethical process of people together attempting to accomplish positive change.”21 After all, as previously stated, leadership is more than just a collection of skills. To capture the collaborative nature of the process of leadership, the C3 model focuses on how skills are developed by individuals, applied by groups, and practiced within communities.

The model is grounded in the social change model of leadership development. Explaining this approach, Astin and Astin write, “Since our approach to leadership development is embedded in collaboration…the model examines leadership development from three different perspectives or levels: the individual, the group, and the community.”22 In explaining each of these three perspectives, they offer guidance as to the kinds of questions that should be addressed at each stage.

- The individual: “What personal qualities are we attempting to foster and develop in those who participate in a leadership development program? What personal qualities are most supportive of group functioning and positive social change?”23

- The group: “How can the collaborative leadership development process be designed not only to facilitate the development of the desired individual qualities (above), but also to effect positive social change?”24

- The community/society: “Toward what social ends is the leadership development activity directed? What kinds of service activities are most effective in energizing the group and in developing desired personal qualities in the individual?”25

These perspectives inform each of the stages of the model. Cocurricular involvement begins with an individual’s awareness and acquisition of skills in the early stages of the model. The perspective then changes to how the process of leadership can be applied by groups seeking to advance their mutual interests and accomplish their shared goals. As individuals become more adept in practicing leadership, they become part of a community of leaders, looking at the holistic impact of their work and developing strategies for working together.

The stages on the cocurricular leadership side of the model are:

- Cocurricular Onboarding: This stage describes how individuals become involved in cocurricular experiences on their campuses. This is not limited simply to exposing them to opportunities, but helps them think consciously about how to select opportunities that are compatible with their personality, interests, and career and personal goals as well as their available time. In this stage, students become aware of the skills they can develop. This stage should also prepare students to think about their participation across their entire time at the institution.

- Cocurricular Involvement: At this stage, individuals are either new to the group, or their participation remains limited or at a surface level. The focus is on individual skill development, acquiring the skill they will need in order to advance to the next level. This requires minimal thinking skills. To advance, individuals will need to simply remember and understand what they learn.

- Cocurricular Engagement: At this stage, groups of leaders take on informal leadership roles. This stage may also describe students in formal leadership roles, so long as those roles do not have a strategic focus (in which the individual is instrumental in determining the group’s goals, objectives, mission, and vision). The focus moves from the skill development of the individual to leveraging skills as a group in order to meet shared goals. Skill development moves to the applying stage. This requires intermediate thinking skills. To advance, individuals will need to be able to apply and analyze what they learn.

- Cocurricular Leadership: At this stage, the focus moves to communities. Leaders must look at how their work exists in an ecosystem of other leaders with both complementary and even competing interests. Skill development moves to the advancing stage in which leaders must find ways to improve their ability to lead, leveraging the strengths of others to meet strategic objectives. This requires the higher-order thinking skills of evaluating and creating.

As individuals transition into their career, they must learn more than just job-search strategies; they must make meaning of their experiences, translate them to potential employers, and then apply them to the context of their career.

The stages on the career development side of the model are:

- Career Transition: At this stage, individuals must make meaning of what they have learned from a variety of learning experiences that have prepared them for their careers. They must find ways to put this learning into words that others will understand. In terms of skill development, they must be able to articulate what they have learned to others.

- Leading Self: At this stage, individuals are in entry-level positions in their career or are transitioning into professional positions later in their career. The focus is on individual skill development and acquiring and becoming aware of the skill they will need to advance to the next level. This requires minimal thinking skills. To advance, individuals will need to simply remember and understand what they learn.

- Leading Others: At this stage, individuals distinguish themselves within their organizations as having the technical and transferable skills necessary to advance. They join groups of others who use the process of leadership to meet shared goals. Skill development moves to the applying stage. This requires intermediate thinking skills. To advance, individuals will need to be able to apply and analyze what they learn.

- Strategic Leadership: At this stage, the focus moves to communities. Leaders must look at how their work exists in an ecosystem of other leaders with both complementary and even competing interests. Skill development moves to the advancing stage in which leaders must find ways to improve their ability to lead, leveraging the strengths of others to meet strategic objectives. This requires the higher-order thinking skills of evaluating and creating.

Clearly, it is far easier to describe incremental learning in cocurricular experiences than it is to describe the world of work because of the tremendous variation within different industries. For example, the Occupational Information Network (O*Net) maintained by the U.S. Department of Labor contains more than 12,000 types of work.26 Within each one, there are different professional expectations, criteria for advancement, and expectations for leadership. While this is a significant limitation, it is also a compelling reason to put forth a model that can help individuals who are thinking about their career growth and development. This information provides a prompt for the new professional to seek to understand these expectations when they enter their industry and place of employment.

Conclusion

The C3 model fills a few important gaps in current leadership theory. It is the first model that links leadership development in college with professional development across time. It further provides a structure for integrating classroom learning with experiential learning. It connects student leadership development with learning from cocurricular experiences, and it describes how to progress through stages of cocurricular involvement in a way that promotes higher-order thinking. Finally, it prompts individuals to think about their career development in a holistic way—starting with cocurricular involvement and leading all the way to leadership in one’s chosen field.

End Notes

1 Owen, J. E. (2012). Findings from the multi-institutional study of leadership - institutional survey: A national report. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs. p. 10.

2 Ibid. p. 14.

3 Dungy, G. (2011). “Campus chasm.” Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2011/12/23/essay-lack-understanding-between-academic-and-student-affairs

4 Griffin, K., & Peck, A., & LaCount, S. (2017). “How students gain employability skills: Data from Project CEO.” In Peck, A. (Ed.), Engagement and employability: integrating career learning through cocurricular experiences in postsecondary education. Washington, DC: NASPA-Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education. p. 8.

5 Peck, A.; Hall, D.; Cramp, C.; Lawhead, J.; Fehring, K.; & Simpson, T. “The Co-curricular Connection: The Impact of Experiences Beyond the Classroom on Soft Skills.” NACE Journal, February 2106, Vol. 76, No. 3, p. 33.

6 Seemiller, C. (2014). The student leadership competencies guidebook: designing intentional leadership learning and development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. 64.

7 Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581−613. p. 582.

8 Astin, H. S., & Astin, A. W. (1996). A social change model of leadership development guidebook, Version 3. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles. p. 16.

9 Robbins, A. (2017, January 27). Personal interview.

10 Great Jobs, Great Lives. The 2014 Gallup-Purdue Index Report. Gallup, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/file/services/176768/GallupPurdueIndex_Report_2014.pdf. p. 5.

11 Ibid.

12 Day, p. 582.

13 Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., & McKelvey, B. (2007). “Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era.” The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 298−318. p. 300.

14 Day, p. 584.

15 Day, p. 585.

16 Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518-29. p. 518.

17 Roberts, D. C. (2007). Deeper learning in leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. p. 17.

18 Owen, J. E. (Ed.). (2015). New Directions for Student Leadership: No. 145. Innovative learning for leadership development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. p. 50.

19 Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Allyn & Bacon.

20 Ibid.

21 Komives, S. R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T. R. (2013). Exploring leadership: For college students who want to make a difference (3rd Ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. vii.

22 Astin, H. S., & Astin, A. W. (1996). p.19.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 O*NET Online. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.onetonline.org/