NACE Journal / May 2022

The effective preparation of college students for careers is an important college outcome. Yet, employers and the public increasingly feel that universities are not doing enough to prepare students for the workforce.1, 2

Among the many approaches advocated for enhancing career preparation in higher education is to provide students more practice in the context of the workplace by increasing course-based opportunities with a career emphasis.3 Career preparation topics may be featured in courses for students, including dedicated career exploration courses or first-year seminars, later in senior capstones, or in courses designed for specific majors. Other course-based career experiences may be emphasized as assignments, activities, or projects. For example, an introductory course in a specific major could include an assignment to interview a potential employer; similarly, a marketing course could require students to work with a community client. Such course-based career experiences elevate the role of faculty in students’ career preparation and tighten the connection between higher education and employers.

Many institutions recognize the value of first-year seminars and career exploration courses to foster new students’ transition to college, particularly those who enter undecided,4 and senior project courses or capstones benefit students as they shift from postsecondary education into the workforce.5, 6 These bookend courses are useful supports for career preparation. However, career preparation could be enriched with more integrated course-based career experiences, including embedded applied learning, career-based assignments, tighter connections between academic programs and employers, and more opportunities for interaction and feedback from faculty about careers.7 To strengthen the connections between higher education and careers, some suggest institutions offer more courses that address contemporary work life, and ensure that experiential and applied learning occupies a bigger place in the undergraduate experience.8

Opportunities for practical experiences via courses that include researching a career interest or analyzing a case study or simulation of a real-life work situation in the major could help strengthen students’ career preparation in colleges and universities. It may also more visibly represent the practical relevance in undergraduate education that many students, families, and state workforce development policymakers wish to see.9 In this article, we focus on courses, exploring the extent to which students are exposed to course-based career experiences using new evidence of college students’ career and workforce preparation. We explore facets of course-based career experiences, along with students’ perceptions of their career preparation outcomes, and the influence of interactions with faculty and advisers on their career plans.

College Students’ Perspectives on Career and Workforce Preparation

To learn more about students’ career and workforce preparation, and in collaboration with the Strada Education Network, we developed a module titled Career & Workforce Preparation (CWP) to append to the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), an annual survey available to bachelor’s-granting institutions to assess students’ experience in educationally effective practices.

The CWP module questions address institutional contributions to students’ career plans, influences on their goals, their level of confidence in their work-related skills, career exploration in the curriculum, and use of career resources and services. Data are returned to participating institutions so they may use their results for assessment and improvement, and we can use this dataset to study quality in undergraduate education.

Data and methods

The CWP set was tested in 2020 and officially administered in spring 2021 to first-year students and seniors at 95 institutions across the United States and Canada. Of these, 85 belonged to one of the eight Carnegie classifications, including 24% doctoral, 46% master's, and 30% baccalaureate, almost evenly split between public and private, with enrollments ranging from 9% below 1,000 students to about the same percent above 20,000. Our analysis is based on 85 U.S. institutions that are largely representative of the range of U.S. institutions by Carnegie, control, and enrollment.

The average response rate for U.S. NSSE 2021 institutions was 30%. Our sample includes 95,600 first-year students and 108,500 seniors at 85 U.S. bachelor’s-granting institutions. For this article, we narrowed our focus to a subset of questions about career and work preparation and learning—specifically career-related course experiences and interaction with instructors and advisers about career interests and plans.

Our analyses are primarily descriptive and comparative to provide an impression about students’ exposure to career-related course experiences, including by NSSE’s eight major categories, and the influence of interactions with faculty and advisers on career interests and plans. We then dichotomize responses to career-related course experience items, creating “high” and “low” course-based experience groups to explore the relationship to first-year students’ perceptions of their early career preparation outcomes and for seniors, the association to their perceptions of support and learning relevant to career plans. To highlight students’ input about career-related course experiences and interaction with faculty, we also examine students’ responses to an open-ended question regarding what their institution could do to better prepare them to develop their career plans or gain work-related skills.

Student Exposure to Career-Related Course Experiences

Students’ preparation for career and work ostensibly happens through a variety of experiences while in college, including in courses—particularly those in the major—in co-curricular leadership experiences, through employment, and in a variety of required and optional activities. Career-related courses provide a dedicated curricular option, with courses early in students’ educational journey typically helping with major and career exploration, while later courses in the upper division of the major or as a capstone can help students bridge the transition from academic work to the field or to real-world problems. Bookend career-related courses in the undergraduate program provide dedicated curricular experiences to help students discover and shape their career plans and prepare for careers and work.

Results from NSSE and the CWP module show that, among first-year students, about 12% have either completed or are taking a career exploration, planning, or development course in their first college year, while 45% indicate that they plan to take a course like this before they graduate. About half of first-year students plan to participate in a culminating senior experience or capstone course.

Overall, results suggest that more than half of entering students expect to take courses that explicitly address career planning.

Seniors’ responses provide a more definitive indicator of actual career-related course; and our results show that only 24% of seniors completed a career planning course, while about 43% have taken a culminating senior experience or capstone course. These results suggest a comparative match between students’ expectation and their actual participation in a culminating or capstone course taking; however, despite entering students’ plans to partake in career exploration and planning courses, only about half of those who intend to actually do so.

Although career exploration and culminating or capstone courses offer dedicated curricular opportunities, another route to adding more career relevance in undergraduate education is to infuse more case studies, real and simulated work-based situations, and opportunities for students to research their career interests or potential employers into assignments and activities in courses throughout the curriculum.

The value of embedding and scaffolding career skills, assignments, and activities in courses in the curriculum has been established in a variety of academic programs, including chemistry and psychology.10, 11

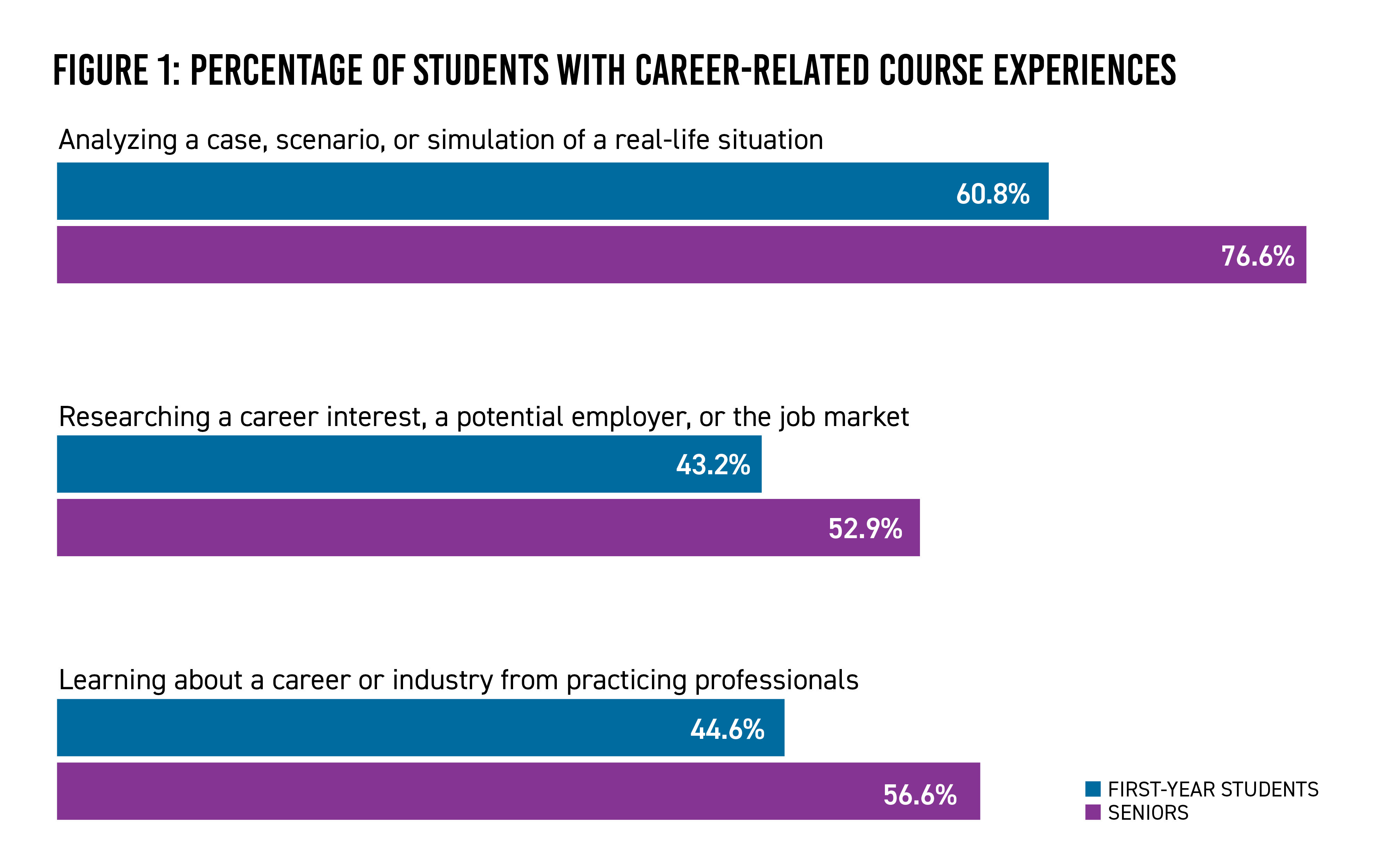

Results for the three items on the CWP module that ask about exposure to career-related experiences in courses reveal that only a small proportion of seniors “never” had these experiences. As Figure 1 shows, more than three-quarters of participating seniors frequently analyzed a case, scenario, or simulation of a real-life situation in their courses. However, far fewer had course opportunities that involved more-direct career experience, with only about half of seniors indicating that they frequently researched a career interest, potential employer, or the job market or learned about a career or industry from practicing professionals.

While course experiences analyzing a case or real-life situation seem more available, lower rates of exposure to more-direct career experiences reveal an opportunity to expand career exploration assignments. Potentially, employers and practicing professionals could be involved in such courses.

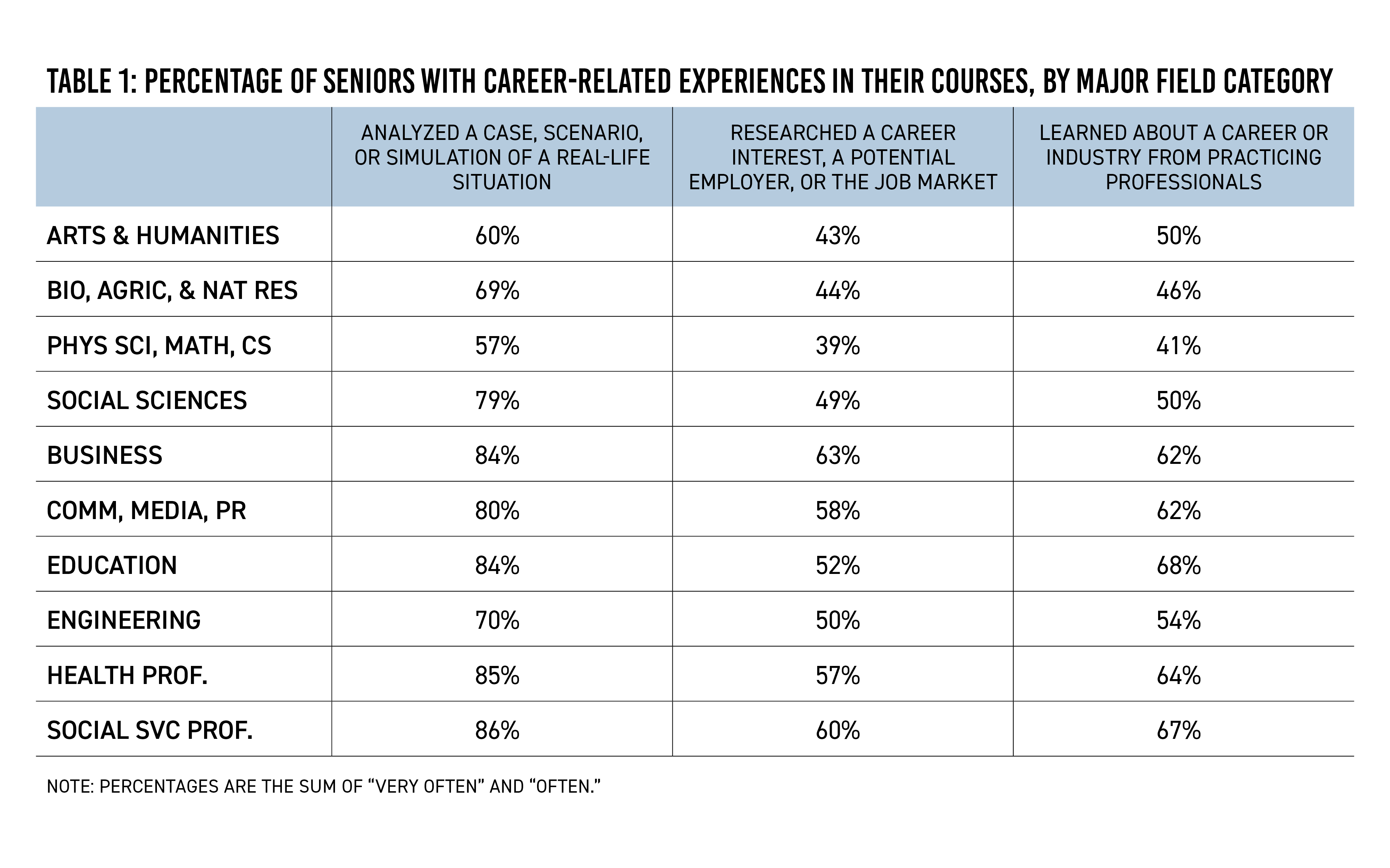

Examining exposure to career-related experiences in courses by major reveals greater variation in students’ experience, with as much as a 20% difference between some majors. (See Table 1.) Unsurprisingly, seniors in practical or applied majors with a more obvious career path, such as business and education, report significantly higher levels of career-related course experiences than seniors in majors where the career path is not as obvious, especially in arts and humanities and social sciences.

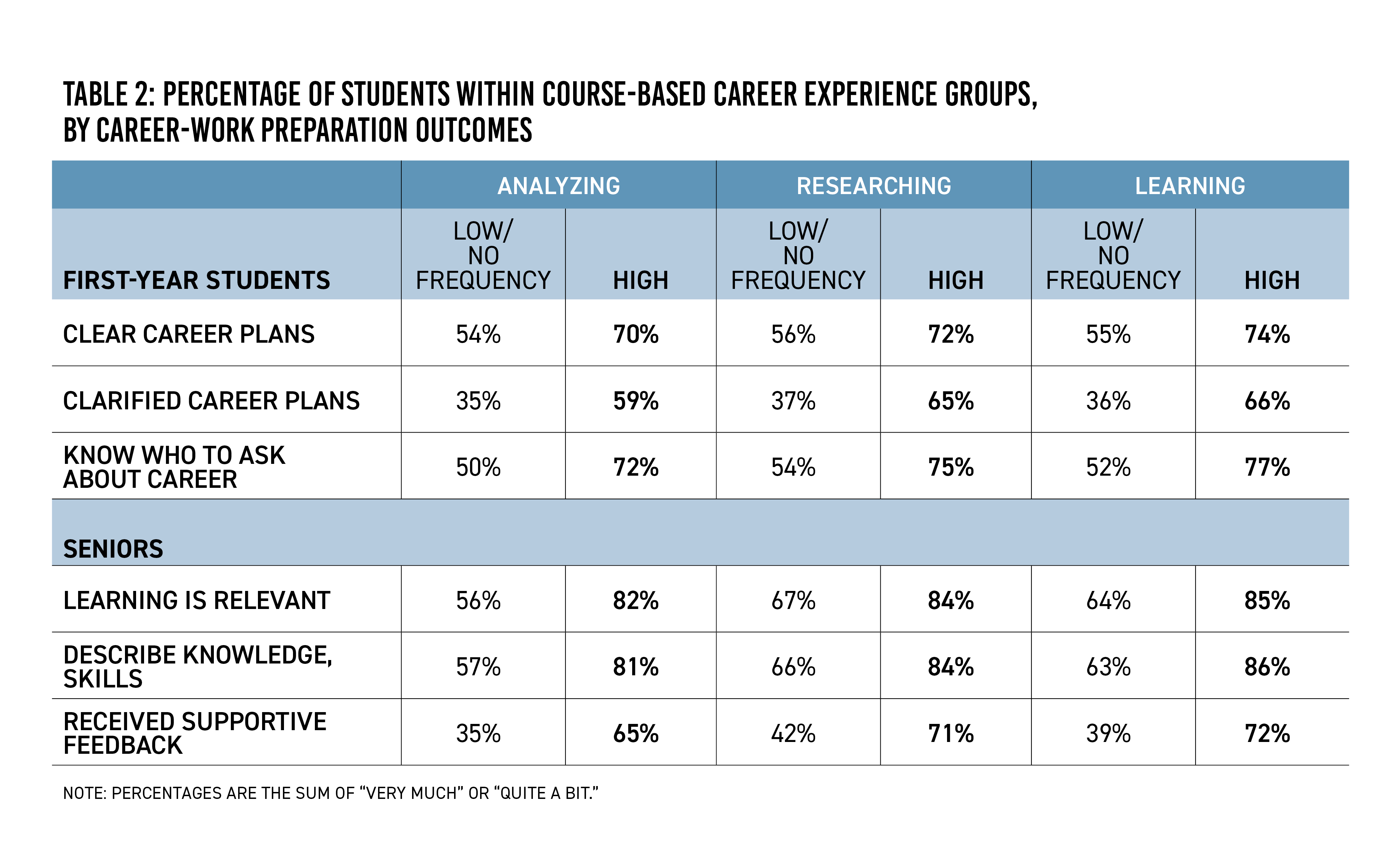

A report from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce asserts that the best way to ensure students get early exposure to careers and have what they need when they enter the workforce is to provide an education that mixes general, cross-cutting, and specific competencies and more exposure to career and work.12 To examine the influence of the three CWP course-based career experiences on career-work preparation outcomes, including first-year students’ career plans and knowledge and seniors’ perception that what they are learning is relevant to their career plans, knowledge, and skills and that faculty are supportive of their plans, we compared students who reported low to no frequency (“sometimes” or “never”) of course-based career experiences to those with high frequency (“very often” or “often”). Results show consistently that both first-year students and seniors who frequently experienced the three course-based career experiences—analyzing, researching, and learning—had higher perceptions of their career-relevant learning and support for career planning. (See Table 2.) For example, results for first-year students in the high frequency group for the course-based experience “learning about a career or industry from practicing professionals,” 66% felt their experience at the institution “very much” or “quite a bit” helped clarify their career plans, compared to only 36% for students who did this “sometimes” or “never.”

The span of the difference between students in the high frequency course-based career experience groups compared to those with low to no frequency is worth exploring. Our data show that across the three first-year student career and workforce outcomes, there is an average difference of about 23% between students who frequently experienced course-based career experiences versus those with low or no experiences. The difference is slightly greater for seniors (25%), with the highest difference (33%) displaying on the outcome of receiving supportive feedback from faculty or other advisers about career plans.

These results demonstrate the strong positive relationship between course-based career experiences and students’ perceptions of their career and workforce preparation outcomes. Importantly, they suggest the benefit of increasing the infusion of career-related applied learning throughout the curriculum to facilitate first-year students’ career planning gains and to strengthen seniors’ perceptions of the support from faculty for their career plans and importantly, the connection between what they are learning and its relevance to career plans.

Faculty and Adviser Interaction With Students and Their Career Plans

Student-faculty interactions are generally considered important in terms of faculty and advisers discussing career interests, influencing career plans, and providing feedback and support to students about their performance and skills related to careers.

Although faculty are subject to criticism for lacking direct connections with current career and workforce issues,13 the conversations and feedback that faculty and academic advisers provide students are essential in terms of developing workforce knowledge and skills.

Foundational to the positive influence of faculty and academic advisers is the extent to which students talk with them about their career interests. CWP results suggest that while only about a quarter of first-year students discussed their career interests with a faculty member, more than half plan to do so. Among seniors, about 45% discussed their career plans with a faculty member.

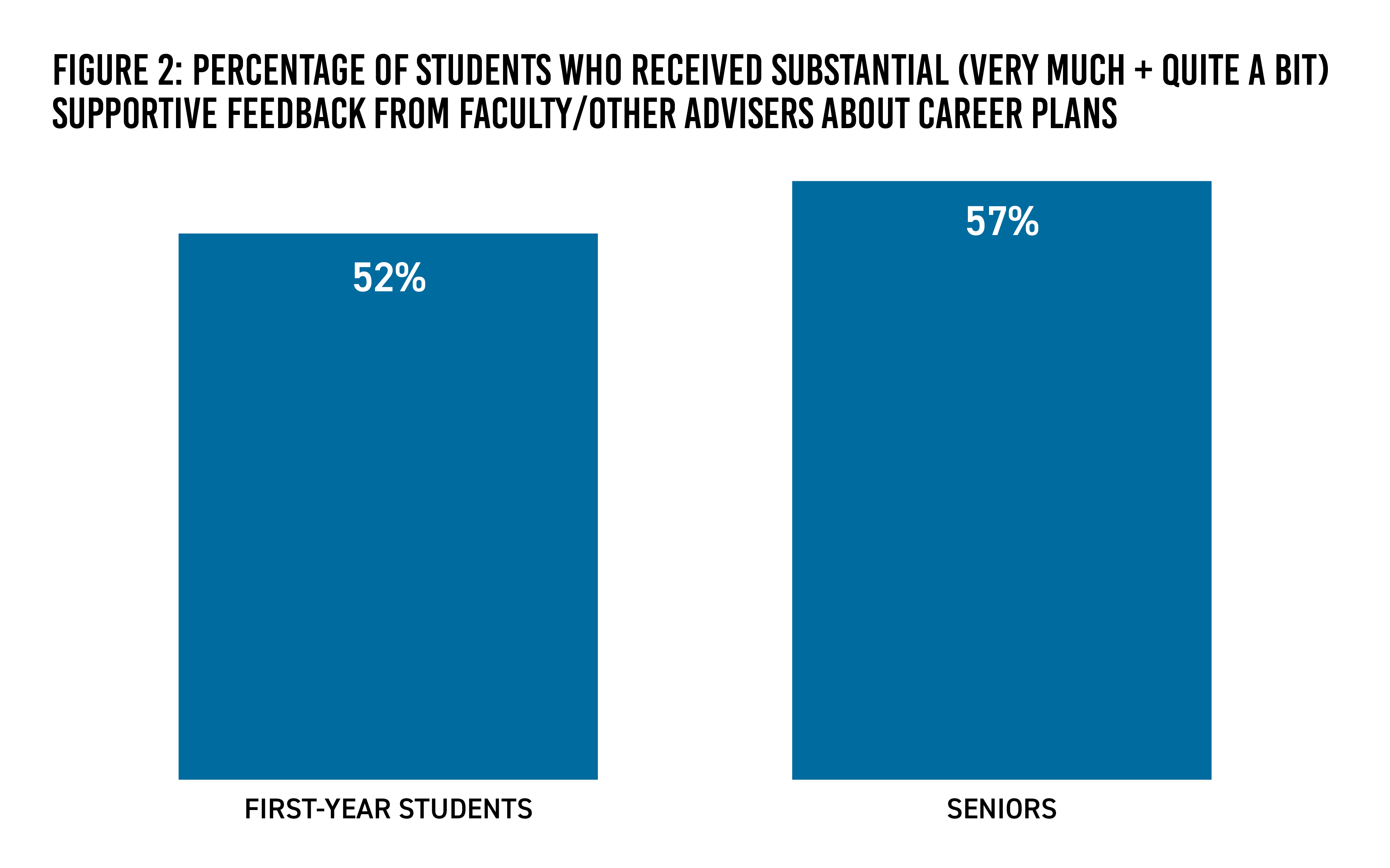

Ideally, this interaction should influence students’ career plans. Unfortunately, only one in three first-year students and only two out of five seniors indicate that their interactions with faculty members or advisers influenced their career plans. Faculty’s low level of influence might relate to the results in Figure 2; these indicate that only 52% of first-year students received substantial supportive feedback from faculty or advisers about their career plans. A slightly higher portion of seniors reported the same.

The similarly aligned results about student-faculty interactions around career—specifically low levels of discussion, limited influence, and little supportive feedback from faculty—suggest that opportunities to intentionally infuse career-related assignments and activities might help.

Implications of Course-Based Career Relevant Higher Education

The assertion that colleges and universities must strengthen the connection between learning and career and that higher education must do more to help students be “career ready” has gained traction.14, 15 Results from NSSE’s CWP module generally indicate that there is room to enhance course-based career experiences and the connection between students and faculty and advisers about students’ career planning and preparation.

Students were asked what the institution could do to better prepare students to develop their career plans or gain work-related skills, and their responses largely focused on increasing “real-life situations” and “connections to employers” and on increasing practical relevance in courses. For example, a first-year student suggested that it would be helpful for faculty and advisers to “explain all the different types of career paths to students to give them a better idea of their options,” while a senior wanted the institution to “get more professors with real-life experience.” A sizeable proportion of students mentioned the need for explicit career preparation classes to develop work-related skills.

Students are taking first-year seminars with career exploration exercises and career planning courses, and later, senior capstones, yet our results show that these intentional career-related courses reach less than half of all students. A strong case can be made for expanding participation in capstones that provide students the opportunity to integrate and apply their learning and consider real-world implications. The pathway between an introductory first-year seminar and a culminating course that brings everything together and helps bridge to career is a consistent way to ensure students have an early opportunity to explore and then tackle complex questions in preparation for their career in the capstone.

Although dedicated courses for career exploration and to cap off the major and bridge to career are worth implementing, our results suggest the value of infusing career-related experiences in courses, including adding assignments and activities that ask students to analyze case studies and real-world simulations, research careers and practical field-based problems, and learn from industry professionals. Findings showing the variation in course-based career experiences by major sheds light on programs where such experiences are strong or could be added. For example, the level of career-related experiences is low in arts and humanities and also the physical and biological sciences. Enhancing career-relevant connections in these majors, and in particular sciences where students who leave often do so because STEM courses rarely teach science in context and show its relevancy to careers, could be helpful to retention. As suggested in an exploration of why students leave STEM, the goals of STEM education could be better achieved by teaching science using more case studies and industry-relevant problems.16

Students’ open-ended comments about what would better prepare them for work and career largely reinforced the idea of increasing internships, including short-term internships, career-related assignments, and applied learning. A senior mentioned his appreciation for a senior project course that required him to work with a company in the community. He added what would make this even better: “I feel like part of the curriculum should include work on resumes and a bit of talking about how to get involved in the community where you would like to work…It would be nice to discuss this with our professors.” Many students mentioned enhancements afforded by technology, such as “have alumni host Zoom meetings in the fields they are working in and invite people with those majors to watch.”

Importantly, our findings demonstrate the benefits of course-based career experiences on students’ perceptions of their career-relevant learning and support for career planning. The stark difference in outcomes between students who have frequent opportunities to analyze case studies and work on real-world problems and connect to careers compared to those with low or no experiences confirms the value. Such course-based approaches provide students practice in solving the problems they may face in their careers, increasing practical relevance and students’ intrinsic motivation and career aspirations. Efforts to design career-relevant assignments could be done in collaboration with employers and industry and career services offices. In addition, many career development centers provide ready-made course activities, including research assignments on careers, informational interview projects, and other ideas to help faculty weave career assignments into the courses they teach.

Student-faculty interaction about careers is a generally underappreciated aspect of career-related education. Only half of seniors talk with faculty about their career plans, and this was not always helpful. Just slightly more than half characterized their interaction with faculty as providing supportive feedback about their career plans. Students also commented that they would like instructors to be more explicit about the connection between course content and careers and to hear more about their faculty’s personal experiences in the field. A first-year student in psychology mentioned “having the professors spend time talking about how they got into their field, and any prior jobs, or any experience would be helpful.” It may also be possible that a greater infusion of career-related course experiences could provide more occasions for substantive student-faculty discussions about career.

The Case for Using Courses as Part of Career Preparation

Overall, our findings highlight the potential role of courses as a site for more career emphasis. There are likely many factors influencing students’ career and workforce preparation, but one route for more-effective preparation would be to focus on the role of the classroom. Our research also illustrates how more intentional integration of career and educational goal exploration and real-work world projects, case studies,and simulations into course content and assignments can help students draw connections between coursework and their educational and career plans. Faculty and academic programs are encouraged to create a more inclusive curriculum and course content in which students can find relevance with real-life situations.

Endnotes

1 Crawford, P. & Fink, W. (2020). From Academia to the Workforce: Critical Growth Areas for Students Today. Washington, DC: APLU.

2 Hart Research Associates. (2015). Falling Short? College Learning and Career Success. Association of American Colleges and Universities, Washington, DC.

3 Fain, P. (2019, August 2). Philosophy Degrees and Sales Jobs. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/08/02/new-data-track-graduates-six-popular-majors-through-their-first-three-jobs#.YiV9Yvq15ls.link.

4 Padgett, R. D., & Keup, J. R. (2011). 2009 National Survey of First-Year Seminars: Ongoing Efforts to Support Students in Transition. Research reports on college transitions (No. 2). Columbia: University of South Carolina, National Resource Center for The First-Year Experience and Students in Transition.

5 Kinzie, J. (2013). Taking Stock of Capstones and Integrative Learning. Peer Review, 15(4), 27-30.

6 Martin, J. M. (2018). Culminating Capstone Courses. In Transformative Student Experiences in Higher Education: Meeting the Needs of the Twenty-First Century Student and Modern Workplace (pp. 41-56). Rowman & Littlefield.

7 Carnevale, A. & Smith, N. (2018). Balancing Work and Learning: Implications for Low-Income Students. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

8 Mintz, S. (2020, September 8). Designing the Future of Liberal Education. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/designing-future-liberal-education.

9 Blumenstyk, G. (2019). Career-Ready Education: Beyond the Skills Gap, Tools and Tactics for an Evolving Economy. Washington, DC: The Chronicle of Higher Education.

10 Ciarocco, N. J. (2018). Traditional and New Approaches to Career Preparation Through Coursework. Teaching of Psychology, 45(1), 32-40.

11 Mertz, P. S., & Neiles, K. Y. (2020). Integrating Professional Skills into the Curriculum: A Summary of Findings and First Steps. In Integrating Professional Skills into Undergraduate Chemistry Curricula (pp. 317-324). American Chemical Society.

12 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (2020). Workplace Basics: The Competencies Employers Want. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/competencies/.

13 Halonen, J.S & Dunn, D.S. (2018). Embedding Career Issues in Advanced Psychology Major Courses. Teaching of Psychology, 45(1), 41-49. doi:10.1177/0098628317744967.

14 Blumenstyk, G. (2019).

15 Fain, P. (2019, August 2).

16 Wernick, N., & Ledley, F. D. (2020). We Don't Have to Lose STEM Students to Business. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 21(1), 21.1.43. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2095.